It occurred to me during the top of the fourth inning that I should have been rooting for the A’s. I’m from California originally, and the A’s are the underdogs, and they haven’t won a World Series since 1989. Meanwhile Rudy Giuliani was sitting behind home plate, cheering, a reminder of the ever-insufferable fans of the Yankees franchise. My sense of what is fair and right would suggest that it was time for the A’s—down 0–2 since the first inning in the Wild Card game, their entire shot at a postseason riding on this game—to win.

But no, I was rooting for the Yankees, because sometime around 2000, I consulted the almanac we had in the kitchen of my childhood home.

It was early spring. I had recently been to a game. I wanted to know, independent of my region and my parents—my dad was a lifelong Mets fan—which team I should claim for my own. The almanac listed World Series wins going back to 1903 and since the Yankees had won the most, by a lot, I decided it would make sense to root for them, logically, because they would win. Thus the Yankees became my team, and thus, 18 years later, against the underdog A’s and my own sense of fairness and California-Boston origins, I was cheering for the Yankees, who were magnificent.

I tell this origin story not because I’m proud that I became a bandwagon fan when I was five, but because this arbitrary decision shaped my allegiance to a team in the same arbitrary way that geography or family can, and because it has rippled across time and place and my own abandonment of baseball. I’m what you might call a lapsed fan.

How did I become lapsed in something I loved so much? Is my attention span fragmented like everyone else’s, so that I no longer have the patience for the endless stop-and-start games? Almost certainly. Do the MLB’s asinine TV deals make it bizarrely difficult to stream a game? Yes. Am I broadly disconnected from the institutions that helped Americans form a sense of identity and community for a century—church and sports and the nuclear family? Perhaps.

Am I disillusioned with baseball? No, it turns out, I am not. The A’s are batting, the bases are loaded, there are two outs, and I am unbearably anxious; in one second everything could change, it could swing the A’s way and that would be the end of it for the Yankees. Luis Severino is pitching to Marcus Semien, and even though I know almost nothing about Severino I love him and I’m practically praying for him, and he’s doing it, he really is, despite all the pressure, the count is 1 and 2 and then Severino throws a fastball—a really fast ball, 99.6 miles per hour—and Semien swings and he’s out, he’s out, he’s out. Severino screams, primally, and so do most people in the bar where I’m watching, and so do I, pumping my first in a gesture that surprises me. I feel like a child.

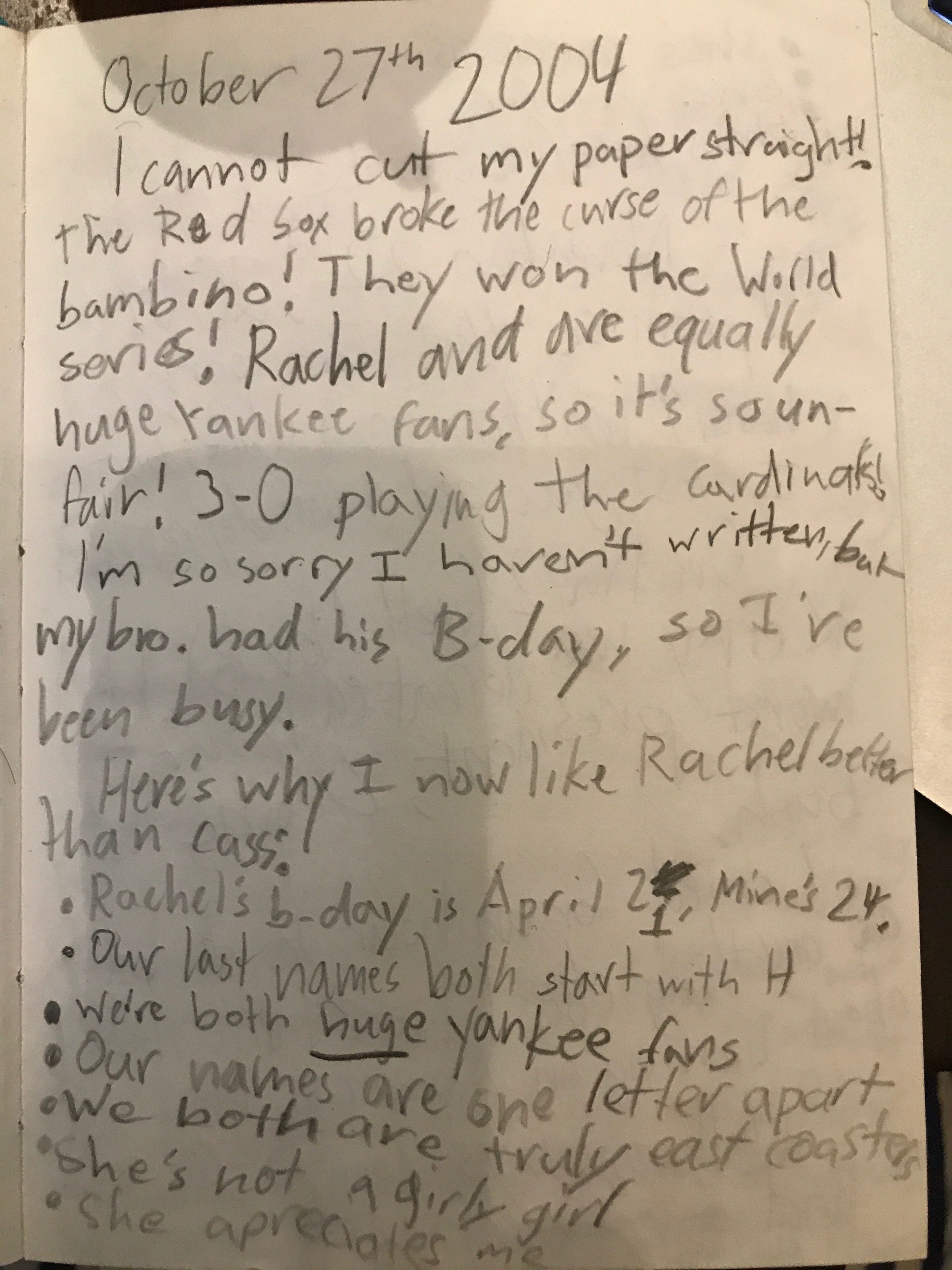

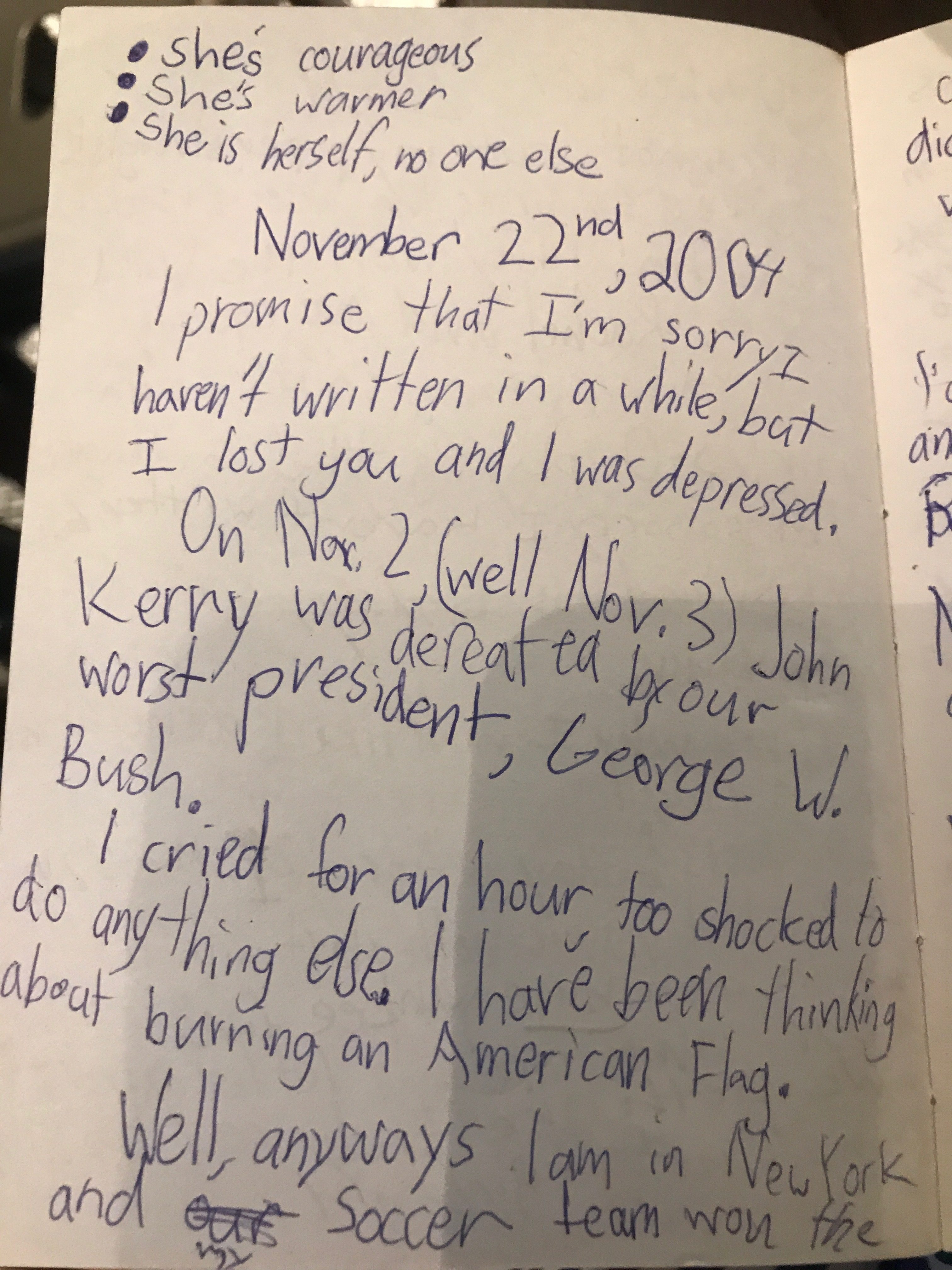

On October 27, 2004, I identified myself in my diary as a huge Yankees fan, underlined. I was nine. The Red Sox had just won the World Series, breaking Babe Ruth’s curse. “Rachel and I are equally huge Yankee fans, so it’s so unfair!” I wrote, clearly not understanding much about fairness. Further down, I wrote how I wanted to be friends with Rachel because–in addition to our April birthdays and our last names beginning with H—of our mutual Yankees fandom. It was a major part of my self-definition, and the Red Sox had shaken it.

The other seismic event of that fall happened a few days later, when George W. Bush was reelected. I remember my shock and tears: I was a lemonade-stand-having, Iraq-War-protest-attending, newspaper-obsessed fourth grader, and it was simply impossible to believe that good hadn’t prevailed. Those two events—the Red Sox winning the World Series and Bush winning the election—were inextricably linked in my head, two wrongs in a short span of time.

The only thing that linked them was time, of course: it was late fall, it was about to be winter, it was 2004. But sports are about time, about suspending and manipulating and limiting it, about creating their own calendars. Baseball has an especially elegiac connection to the seasons. A. Bartlett Giamatti, briefly the commissioner of baseball before he died of a heart attack, wrote about this in his essay “The Green Fields of the Mind,” which is among the only pieces of writing that can reliably make me cry:

It breaks your heart. It is designed to break your heart. The game begins in the spring, when everything else begins again, and it blossoms in the summer, filling the afternoons and evenings, and then as soon as the chill rains come, it stops and leaves you to face the fall alone. You count on it, rely on it to buffer the passage of time, to keep the memory of sunshine and high skies alive, and then just when the days are all twilight, when you need it most, it stops.

Giamatti was getting older when he wrote this—he noted that summers seemed to be slipping by faster and faster—and though I am not, not really, I also am because of how time works and of how it’s no longer 2004. It’s nearing the end of 2018, and I don’t know many of the players anymore, except the really famous ones—Aaron Judge, Giancarlo Stanton. My childhood heroes turned out to have been abusing steroids or to have been Republicans (Roger Clemens, for one). I feel pangs for the ghosts of players past who have remained pure in the memory: Mariano Rivera, the greatest closer of all time; Derek Jeter, of course; Hideki Matsui, whose jersey I used to wear to sleep. “Where have you gone, Joe DiMaggio?” and the endless march of time and all that.

But holy shit baseball is good, when I return to it in October. A full count and a foul ball, the suspense continuing. The signals between pitcher and catcher. A double play, when it’s the Yankees making it, and a base stolen by anyone. The slow movements of outfielders when they’re sure they’ll make a catch. The pitcher, good God, I love all the pitchers—how they can wind up over and over, keeping their cool, staring down the batter, controlling play, uncoiling in one wild motion and releasing pure speed.

The game really broke for the Yankees in the bottom of the sixth. Aaron Hicks hit a line-drive double and sent Aaron Judge home. After a wild pitch Hicks advanced to third, and the A’s relieved their pitcher, who then walked Stanton. There were no outs and two men on base. My heart was positively racing, and then Luke Voit hit a triple that almost went out of the park and sent them home. Then Voit ran home too on a sacrifice fly, and the score was 6–0 and everything was beautiful in New York and it seemed rather certain that we—I, the people in the bar, Luke Voit, the fans wildly beating the sides of the stadium, Rudy Giuliani—were going to win tonight.

I rode out the last innings out in the bar, holding my breath as the A’s scored two runs. I thought about the absurdity of having a team and feeling a false sense of belonging, and how nothing turned out the way I might have expected in 2004: politics, sports, friendships, family, me. Things have gotten worse since then, or else I’ve gotten older, or both, and I’m not really a baseball fan anymore. But the Yankees are still brilliant, and they’ve gone on to face Boston. I’ll hitch my hopes to them again, penitent for my late-season fandom, promising that next year I’ll really be back (though I probably won’t be). But this October baseball will be a bright, evanescent hope as everything else around us starts to die; baseball will stave off winter, baseball will stave off death, baseball will stave off politics and disillusionment, until it won’t, of course. But it will be good while it lasts.

Sophie Haigney