I was eight years old when my brother died in the careless Sosoliso plane crash of December 2005, and soon after, I developed a stomach ulcer. Alongside medication, I was placed on a diet that excluded beans, pepper and all fried food. Within my family’s regular diet, all I could eat without disastrous consequences was: the regular morning bread and tea, boiled yam, plantain, potatoes and custard. Managing the ulcer was tight, and in the aftermath of my brother’s death, there were many things I no longer had the time, energy or heart for. My body was one of them.

Planes weren’t the only things falling from the sky that year; puberty nosedived into my eight-year-old body as if ravenous for my childish innocence. Along with my first pair of prescription glasses came migraines, breasts, more hair than ever before, menstruation, cramps and body expansions that left tallies on my upper arms and thighs. My new diet only made matters worse—it was full of sugars and carbs, and my primary source of protein was the sugary Peak milk—and I felt my body fight, slip out of my control and change dramatically under the stress of it all. Like with my body, I could no longer make sense of the life or family I thought I knew either. In the storm of my brother’s death, my mother was where the lightning struck. She was grief-stricken, grief-dazzled if you like. My father got busier because he joined a political party and so was rarely ever at home, a change that now makes sense to me as his own way of protesting, amongst many other things, his son’s avoidable death.Collectively, my siblings and I worked hard to ward off our awareness of the fact that our brother should have returned from school. Amidst all this, what did a body’s pain matter?

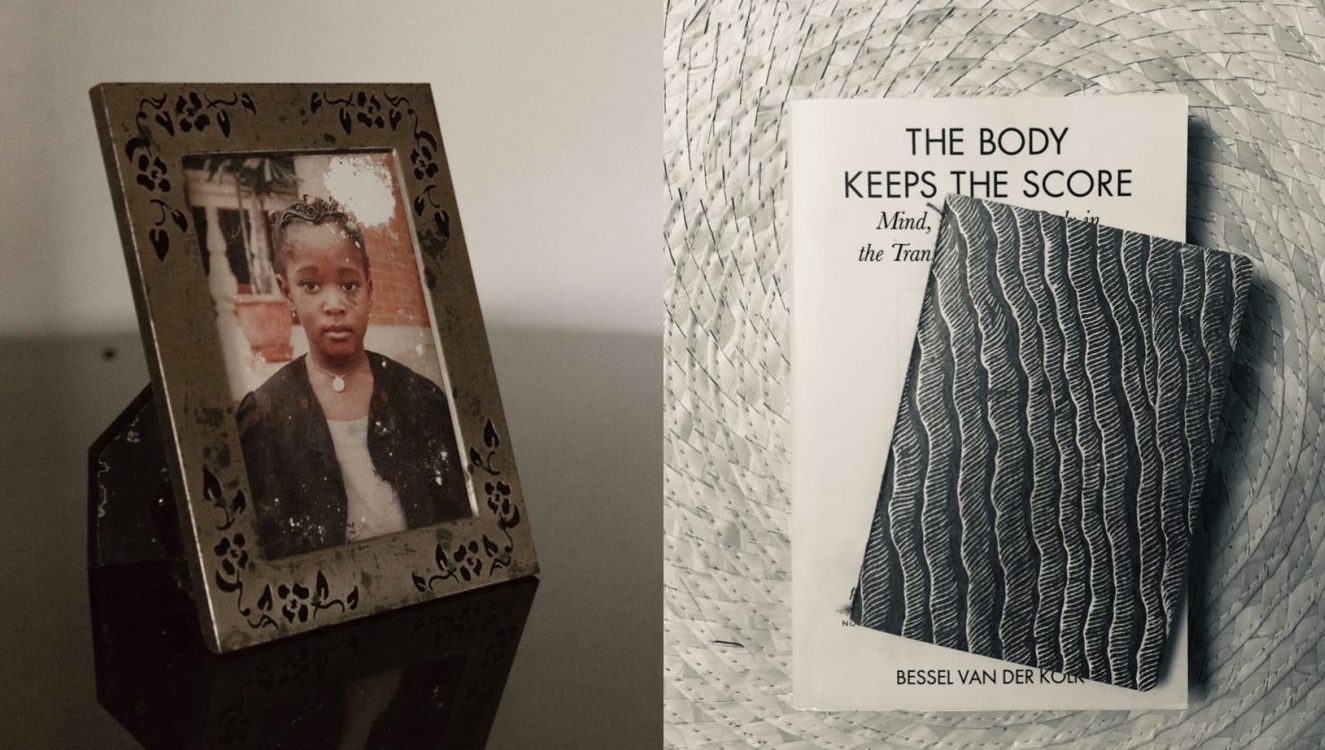

And so, I stopped trying to make sense of my body’s tantrums and started taking them in my stride. Thankfully, I had advanced classes, math competitions and entrance exams to distract from my unkind puberty. Between the ulcer and the stress of living in a house moulding with transmuted trauma, I discovered the magic of food, in particular the magic of a sugar- and carb-based diet. One of the few memories I have of that time of my childhood is sitting at the bottom of the staircase, staring out through the slit of the door into our backyard, seeking consolation in a mug full of a 1:20 ratio mixture of water and Milo. By the time I was 10, I could not recognise myself in the mirror. Over the two years, my body had only expanded with time and alienated itself from me with its foreign bulges and weird smells. The girl in the mirror wore my mother’s UK women’s size 12/14 clothes. Strangers in the market, neighbours, teachers, classmates, friends, my parents, everyone had an opinion about her body, which they were always eager to share. Sometimes they called it “mature,” which meant sexually appealing. Mostly they called it fat, fat like a sin. I understood then that the mirror-girl was despicable, and the only “me” I recognised was the one whose five-year-old face was immortalised in a frame on our parlour wall. I promised myself that one day I would get back to that version of me, but in the meanwhile I was resigned.

I went to boarding school the year after, excited not only to leave my family home but also to shed my so-called baby fat. Everyone knew boarding school was where every unruly body got a shape-up. I was silently very intent on this desire to lose weight, and so after my first year, my body carried my once-snug checked uniform like a hanger. I was back to wearing clothes from the children’s section. Two years on and at 13, having gained some mastery over puberty, I emerged into a slim-faced, hourglass, spare-bodied girl whom my sisters and I envied. I envied her because I was always afraid she was not mine and that she would leave me just as suddenly as she had appeared. This girl joined the dancing team and tried out for the javelin, soccer and track teams. She was kicked out of all those teams for lack of skill and an excess of self-consciousness, but that is beside the point. The point was the idea that she had the body for any and everything.

Keeping that body was a battle I fought hard and eventually lost. At first, it was not so difficult, because boarding school kept me hungry. On an average day, all I had to eat was some bread and tea, a three-in-one pack of digestive biscuits, one serving-spoon portion of rice and one serving-spoon portion of spaghetti. This was not atypical for the girls in my school. In the boarding school I attended, money and most material possessions were banned and so our major currency was reputation, or “reps” as we called it. One’s reps depended on one’s popularity, good looks and—because we were a competitive school—good grades. It was a distilled microcosm of wider society, only stricter and more severe. And so, it was crucial that I keep the new body I had acquired in check, quite literally. Girls in my school manually took in the darts and seams of our checked dresses to make them snug on our new breasts and starved waists. This was also an act of faith: you crafted the mould and waited for your body to fit. The proudest I have ever been of my body was aged 14 in my third year at boarding school. “Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at,” John Berger famously said. And so at 14, looking through the eyes of boys in my school, I saw that my body was attractive. Their trained eyes could tell when a girl had had more than one serving spoon of spaghetti for dinner. If her stomach folded when she sat down at her desk during study hall, she was a gredge, a disreputable glutton. “Finally,” I thought, “here is a body that is recognised and so I can recognise.”

Late last year, I was volunteering at a conference when I got into a conversation about body image with two other women on the team. One was a mother who could not stand her body since it refused to “bounce back” after pregnancy. The other used to be fat when she was younger and was still anxious about returning to her former size, like a house owner traumatised by an armed robbery. All three of us desperately wanted to change our bodies or, at the very least, subdue them. Earlier that week, I had mentioned to my friends that I was writing this essay on my relationship with my body, and a me-too conversation ensued. Two of them were ballet dancers when they were younger, and they too had had eyes snooping around their waistlines to measure their worth. Almost everywhere I turned, there was a woman like me with a story about the relationship she has with her body, where her sense of worth hung on a thin thread in the wind of the many eyes of men, older women, younger women, parents, the media, and even herself, inevitably. Under all these eyes, her body suffered the pressure to be impossible.

I have since thought about what it means to have a body. To be a person, in possession of a body as a separate or largely autonomous entity. In his book The Body Keeps the Score, Bessel van der Kolk describes how the body remembers what your mind makes sure to forget. Since I moved to the UK for university, academic stress has brought me more pain than my mind can afford to remember. But my body, choiceless as it is, has always kept score. If I was not losing hair over university applications, the stress from deadline season was reviving my stomach ulcer. No matter the day or season, migraines are a weekly constant. The person I am today is a high-achieving student who is proud of academic achievements which often come at the cost of her body’s wellbeing. At the end of the day, my body always bears the brunt of my trauma, whether physical or psychological. It absorbs the shock and makes do. My body, like a lot of bodies, makes do by expanding. She expanded after my brother died. Expanded in the grieving years after his death. Expanded viciously in the autumn of my dreadful third term during my International Baccalaureate years. Expanded when I thought it was okay to juggle freelance writing and photography with a part-time job during university term-time. Yes, she expanded, but I can’t sit here and say it was all out of her will and all in spite of my doing. I learnt to cope with stress by making my body pay for it by binge-eating and all associated binge-eating discomforts. I learnt to cope with stress by transferring it to the closest vulnerable body in line, like the abusive patterns of relationships I grew up around taught me to do. I learnt to cope with stress by dissociating myself from my body, neglecting her and assuming the irresponsibility that somehow, last last, she will be all right. After all, something’s gotta give, right? But for being there with me through thick and thin, my body deserved better, and it took me twenty years to realise this.

Over a decade since I was diagnosed with a stomach ulcer, my body’s first rebellion, the crack of dawn in my relationship with my body came one morning in my therapist’s office, where I confronted the fact of my relationship with my body in all its abusiveness. In talking with him, I was finally able to hear the question my body has been posing all along: “What is a long-suffering body to do when it is continually assailed by the demands of narrow and impossible beauty standards and yet has to go through endless changes and expansions to protect its owner? Who will guard the guards?” Among other things, my therapist’s office gave me the space and courage to believe that I did not have to internalise pain and anger, only to take it out on my body. That my body does not have to be the punching bag for my pain. I had to accept that when I falter, as the human I am, by resorting to my body as an exit wound, and my body, as the body it is, responds by expanding, shrinking or malfunctioning, it is I who failed my body and not the other way around. Finally, I had to accept that my body was not the problem.

Since then, I have made resolutions to be kinder to this body who is my closest companion. I actively removed myself from spaces—mostly online—that drip-fed me subliminal messages of what a female body should look like. I stopped buying clothes a size too small in faith and put more effort into attending classes at my local yoga studio. I also started taking pictures of myself frequently as a way of coming to terms with the image of my body as it is, not as it can be or as it used to be. These days, my binge-eating episodes are fewer and farther between. This is just the beginning of a lifelong process of choosing to fall in love with myself and my body because we deserve love. And yes, I still ask my sisters if I look like I’ve lost or gained weight when I FaceTime them, just like our mother asks us. Yes, some nights, I feel as though I can see the calories from my dinner on my collarbone. And yes, I have those mornings when I wake up thinking, “What did I eat yesterday?” and then subconsciously fix my worth for the day on that answer. But the process has begun, and as my mother always told me, “Whenever you wake up, that’s your own morning.”