All gay people fascinated me when I was a kid, but no one quite so much as my dad’s best friend, George. By the time I came along, they’d been friends for about twenty years. George was the first gay person I knew, and my role model by default.

I never found it interesting that men and women would find each other, fall in love, and marry. While I was growing up, it was everyone else who interested me. The singles, the queers, the people with clear mental illness that made it impossible for them to live a “normal” life. I was obsessed with my mother’s uncle Larry, the one perceived homosexual in the family, who only saw the rest of us at funerals and reportedly owned no furniture, a man who was baffling to all who knew him.

George was tragic. This fact only made me love him more. It was the gayest thing about him. George was not especially flamboyant or bitchy. He didn’t make campy jokes or savage fun of heterosexuality. He might have even passed as straight to people who didn’t know him.

He grew up as one of ten children, the son of a doctor in Lutherville, Maryland. He was born in 1950, the same year as my father. They met during their freshman year at Fordham, through their friend Stephen Lynch. Lynch was initially living off campus uptown with an old woman, and George was seeking a roommate. They moved into a one-bedroom apartment together. According to my father, it was common practice for Lynch to bring girls home to fuck while George would pretend to be asleep in the bed across the room. “It seems kind of inconsiderate,” my mother says whenever my dad tells this story. “Like he didn’t really see George as a person.”

He was a short man who wore glasses and bore a passing resemblance to Wallace Shawn. He was famous for disappearing during social outings. They would all go to their college hangout, the Pennywhistle Pub. One moment, George would be with them in the booth, listening to my father extol the virtues of the Bee Gees’ “Massachusetts,” and the next, he would be gone.

“Where’s George?” became a punch line: mysterious George simply had had enough of their company, or of straightness, or of social life. George, who would give you the shirt off his back, had pulled an Irish goodbye yet again. During these outings my father would turn around like Orpheus, only to find that George, his Eurydice, had disappeared.

Being gay men was the thing my father and I always had in common, despite the fact that neither of us was, in fact, a gay man. Queers had found my father early, during his childhood and adolescence in Waltham, the Boston suburb where he grew up. In a culture of rigid heterosexuality and middle-class gentility, my father found himself constrained. He sought out, and was sought out by, the people who made him feel like life could be more than what it appeared to be on the surface. In a culture obsessed with the blandness of Doris Day and Perry Como, my father chose, and was chosen by, the Douglas Sirk fans.

Dad tells stories of being taught by teachers he knew were gay without ever knowing what “gay” was. With his high school friend Barry Kennedy, who killed himself in 2003, he created a contest called “Miss Elite,” in which girl classmates were ranked on poise, class, and taste. Hearing these stories, I couldn’t imagine how anyone could not read my father—who still takes every opportunity to burst not only into show tunes, but into the deepest, gayest cuts imaginable: “Ladies Who Lunch” from Company, “Rose’s Turn” from Gypsy—as gay. At one point during high school, I caught him bringing up freshly cut wood from the basement while singing Lady and the Tramp’s “He’s a Tramp (But I Love Him)” in a gentle tenor.

I always wanted my dad to be gay: The groundwork was already there. I longed for my father to come out to me in an intimate scene, move in next door with his boyfriend, and leave my mother and me to live together without him: She would become the true parent, and he would become the queer friend I wanted. He would become a kind of George.

According to my father, George never formally “came out.” Rather, during one summer in the late ’70s, he told my dad he was in love with a man—their mutual acquaintance. Between that isolated confession and the early ’90s, when George was living the high life in New York, George had begun dating men in earnest, mostly younger men. George never moved in with any of them, but he seemed to enjoy these affairs, boasting at one point to my mother and father, “I’ve become irresistible!”

My parents met at a summer stock program in the 1970s. They married in 1976 when he was 26 and she was 22 and, before having my sister and me, lived together in New York, in an Upper West Side brownstone near H&H Bagels. She woke up before dawn to work in bakeries around town; he worked at a bookstore and wrote plays and got them produced. During this time, they saw a lot of George. In the early ’80s, when he moved to western Massachusetts, my parents followed, with my older sister Nicola in tow. In 1988, they moved into the house in Northampton where I grew up, the house they live in to this day.

In the ’90s, George landed a job at NYU and ended up moving back to New York. The school put him up in a series of lavish apartments. I remember one in particular, close to Washington Square, a typical early ’90s–era New York apartment with a dimly lit, seemingly gold-plated lobby, a doorman, a fake Christmas tree—the kind of place where the rich, evil suspect on Law and Order might live.

George inhabited these spaces as if he’d been born in them. To me, he was the consummate New Yorker. He was what New York meant when I still thought it meant something—glamour, class, and most of all, freedom. At that time I wasn’t really able to imagine a future for myself, ideal or otherwise, but if I had it would have resembled George’s reality: tasteful, understated, Rothko prints hanging on the wall, a glittering view of the Chrysler Building outside the sleek modern windows. He opened his floor and his sectional not just to us, but to whatever teenage friend my sister decided to bring along on the trip. In the morning, we slept in while he ran out for knishes to serve us for breakfast.

He bought us shit, too, over the years. A guillotine instrument for cutting bagels. A set of blown-glass Christmas ornaments from Paris. He gave my sister a pillowcase full of pennies, which seemed like an incredible fortune to her as a kid. He gave me a small journal that was also a necklace. I must have been about six or seven. I wore it around and wrote in it.

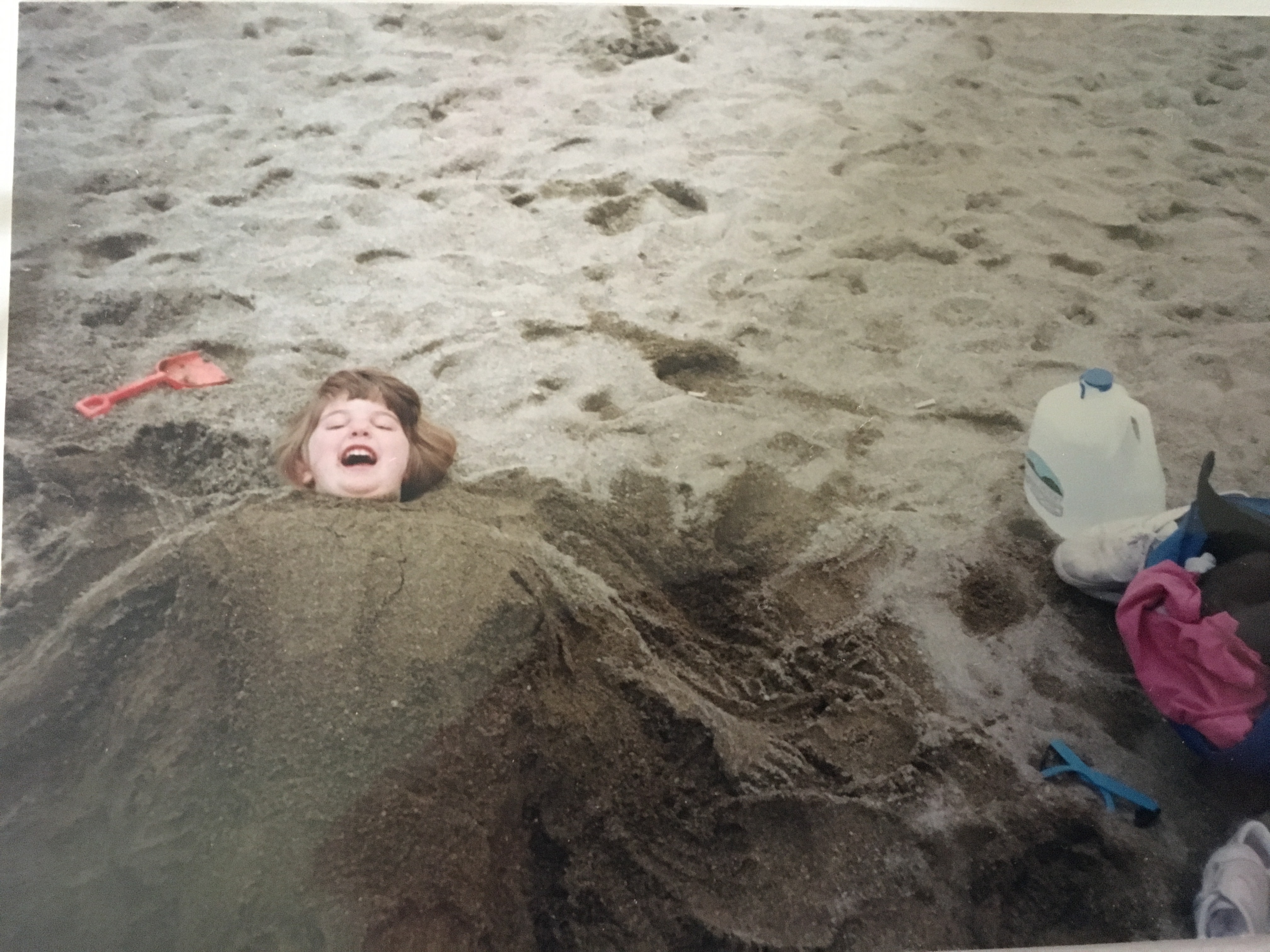

I remember an encounter with him and a lover when I was a very young kid. A house on the beach. Something that seemed like Martha’s Vineyard. It was me, my father, and George and a boyfriend. A package of scented markers that someone—likely George himself—had given me. I don’t remember the other man or much about the encounter, but I liked that they were a unit: two men living by the sea, in a beautiful house.

When I was a kid, almost every summer we took a family trip to Provincetown. Every summer it spooked me for reasons I didn’t understand. I hated the drag queens who would come up to you in the middle of the street and harass you. I hated the feeling of ghostliness and death that descended on the town at night. It felt like being hunted.

On one of our visits to Provincetown, when I was around 10, I came upon my father sitting on the steps of a bookstore, his body hunched in sadness. We’d split off during the family vacation—me with our family friends and their daughter who was my age, and my dad alone on his quest to find a friend from high school, Jeffrey Kresser, who worked at the bookstore. Kresser had come out to their whole English class in their junior year of high school, back in 1966. In 1987, on the weekend I was conceived, my parents wandered into this bookstore to find Kresser, and over the years they’d kept coming in to say hello. At some point, Kresser shared with my father that he was HIV positive, and today, my father had gone to find Kresser and had been told he was dead.

Meanwhile, with the others, I had been suffering the punishment of vague adult disapproval. I had done something bad—I can’t remember what. Been reckless, been loud. I felt ashamed. For one of the first times in my life, I wanted to cling to my father. Seeing him on the steps, knowing that his friend had died, I felt a rare spark of kinship with him, without really knowing why. But the way he’d described Jeffrey Kresser had alerted me to his gentleness, his gayness, his “like me”-ness. We sat on the steps, watching the men walk by, many of them laughing and making out, because that’s what men do in Provincetown, as he took in the reality of Kresser’s death.

I didn’t know what AIDS was, but I knew it was a thing that killed gay men, a thing that killed “like me” people. I didn’t technically lose anyone to the AIDS crisis, and yet I did. I lost people who, had they lived, might have loved me. Whom I might have loved. When I think about AIDS, I can’t help thinking—selfishly, to say the least—that I might have had more fathers.

I sat there next to my dad as he mourned, and said nothing.

I grew up knowing George as a very generous presence in all ways. We would go out for bagels in the pathetic bagel shop we had in Northampton and he would listen to me talk about whatever nine-year-old bullshit was important to me. He seemed to be always smiling, always humble, always giving. Generosity can be a way of showing people you love them; it can also be a way of keeping them at arm’s length. “Here’s a gift: Now don’t look at me.” I knew George loved me and that I loved him, but I remember George hovering over my life more than I really remember him in it. He visited, but didn’t really settle into the experience of spending time with us. He was there, and then he was gone. I almost remember the gifts he gave me more than I remember him.

In the ’90s, George had a boyfriend who was younger, a student who’d made a short, risqué film about gay life. This film was somehow so popular that my sister can recall flipping through the pages of Sassy magazine around this time and coming upon this filmmaker on the Boys We Love page. Somehow it happened that during this teen girl ritual George was present and, pointing at the picture of the impossibly cute boy, said: “That’s my boyfriend.”

I found out later that some of these young men he dated enjoyed upkeep funds from him. He had paid a boyfriend to decorate his apartment. It seemed he didn’t think he was irresistible.

From the moment George met me I was trans, but he didn’t know it. It would take me until the age of 20 to come out. Trans people often fear they’ll be rejected or cast out of the house or worse after coming out. I felt like I would have to blurt out the words and then disappear from my family’s lives for years. Not so much for them to process it, but for me to avoid having the painful, years-long conversations that would follow.

George may have feared these conversations, too. With his boyfriends, his generosity was more about deflecting. Trying to create and preserve an illusion. Trying to be worthy of love through buying shit.

Like most of us growing up then, I knew what I was, but I didn’t know the word for it: In Northampton, where I grew up, there prevailed a highly liberal but also limited sense of what transness was and could be. In a culture of “Why wouldn’t it work to just be a butch lesbian?” I didn’t have a sense of my own reality. I knew about gayness, but I knew that that alone didn’t cut it. It didn’t get to the meat of My Problem.

I knew that George did not have a problem like my problem, but that our problems were similar. Not because being gay and being trans are so alike in nature: they’re not. Because George seemed to want something impossible, too. Something the world had always told him he couldn’t have. Something that I, as a kid, presumed to imagine into existence. Two men getting married, I thought to myself as a child, having no idea that anyone had ever thought of it before. What an incredible, wonderful, impossible thing!

George was watching Petulia with my mother the night she went into labor with me, in 1988. In typical George fashion, he was gone by the time she gave birth the next day. George disappeared from our lives by increments for years, only to show up eventually, gifts in hand. But at a certain point, he started to really disappear. This was in the mid-late ’90s: George and my father were older now, in their early 50s. George’s disappearances, odd and comic to my parents as young adults, now seemed like an insult to their lives, to their shared past. My father hated the fact that George would dip out whenever he chose, without responding to calls or emails. My dad also, at this time, seemed to be looking for things to be mad at. Anger provided release. Through his 40s and 50s, he would enter the bathroom to literally “yell at God” about anything. Sometimes he yelled about George. Sometimes he yelled because the weather was bad for grilling.

The gradual loss of George cast a great shadow over what was already a trying time for him. As a writer who seldom committed to 9-to-5 employment (there were professorships at colleges, on and off through the years), my father clipped coupons obsessively, wrote novels and magazine articles, and stayed at home with me while my mother pulled night shifts at the hospital as a labor and delivery nurse. He spent middle age in a state of perpetual fear, trying to scrape it together and looking at every elderly cashier at the supermarket with a dismal fantasy that this would someday be his own fate. I’ve inherited this same fantasy: maybe it’s because I share the same unstable profession, maybe because we share a sense of doom.

Sometime in 1997 during a school vacation, my father took me to New York with him on the train. He sat silent as we rode, perhaps building up his store of anger so as to be able to release it at the perfect moment. I remember not knowing exactly where we were going until we got to the NYU admissions office, where George, who had just pulled another, lengthier disappearing act, had worked for years.

My father entered yelling. George absorbed my father’s wrath calmly. He offered me one of the uneaten donuts that sat in a box on his desk. I didn’t know why my father felt he had needed to bring me on this errand, except as a kind of weird guilt prop. Nor did I know which side to take, if any. Each of them saw me, apparently, as belonging to the other. To George, I was a product of the heterosexual culture, a sunny, blond-haired kid. To my father, I was proving to be something else. I was reaching the point where it was no longer cute or funny to have gender problems. I had already begun introducing myself to his friends and associates as “a boy,” and he’d started to be embarrassed by it. As puberty approached, my friends and family seemed to be looking through rather than at me. If they hadn’t been, they would have seen it: the thing I was too scared to look at in close-up.

I pardoned myself for this blindness, but gave them no quarter. Instead, I began a lifelong process of distancing myself from the people who professed to care about me while neglecting to think of me as male, neglecting to pick up on the many hints I’d been scattering since the age of four, neglecting to put two and two together. This was the beginning of the all-or-nothing philosophy I’ve lived with for almost 30 full years: if you don’t love my neuroses, my coping mechanisms, my transness, my apartness, you must not love me. In the years after coming out, I was extremely angry at my supportive family, as many queers are. I felt that they accepted me without trying to or even wanting to understand me. I resented having to explain over and over again something I could barely articulate myself, never mind defend: “I’m male, but not really, and I want to be happy about it but I’m not, but you should definitely support me anyway.”

During a childhood where I’d felt, emotionally, that I had to fend for myself most of the time, I was eager to fix things by saying to my parents: “Here’s the missing piece.” Instead, this revelation created problems. It created questions, on their part, stress and a feeling of imposter syndrome on mine. It was a mess. Half the time I wanted to run away and live my life in secret, far from the critical gaze of anyone who’d known me “before.”

In George’s NYU office, eating my donut, I knew that my position here, as witness, was strange. On the one hand, the donut had been another gift-cum-distraction. “Here’s something shiny—don’t pay attention to what the adults are going to say.” My father, I imagine, had brought me because he wanted George to understand the fact that it wasn’t just himself, my father, who was hurt during these disappearances. I was hurting, too. I don’t know if he actually knew this or wanted to use me as an ideological prop: “Think of the children!” Either way it was strange: To George, I must have been the symbol of the guilt and shame he felt about cutting us off when the going got tough. To me, George was also symbolic. He was an adult who made the choices you don’t see on TV, the choices you can’t easily explain away in 90 edited minutes. My father was now yelling at George, that crucial fag in his life, to express his pain, while I, the other fag in his life, stood there, understanding that George was someone who simply didn’t want to be seen if he couldn’t be seen as perfect, or upstanding, or successful. This is the opposite of a textbook fair-weather friend. Rather than being a friend who leaves at the first sign of your trouble, George left at the first sign of his own. The idea of asking the people who loved him to bear witness to what he saw as his failure or weakness was, it seemed, too much.

Not long after our trip to his office, George stole some money from NYU and got found out. There were no more visits to Washington Square West. George transitioned from being the kind stranger to seeking the kindness of strangers: old boyfriends, people he wasn’t ashamed to ask for help from. In other words: people who weren’t us.

When it became clear in late 2001 that George was not coming back without being found, my father started to reach out. But George didn’t seem to want to be found or followed this time: that message had become clear. Every so often he’d reach out to my father with muddled, confusing details about what his life was now. Come join me in a Pride parade. I’m working for the Catholic Church, come meet me at a service. I’m staying on a friend’s couch. I’m working for a small university. I don’t have a job. My father would dutifully follow all instructions, and George would bail every time. On top of everything else, he had lost two ex-lovers in the World Trade Center. He said he didn’t want to deal with anyone who hadn’t experienced a loss of that magnitude.

Dad changed. There was no heading to the office to set George straight. There was nothing: silence. In the absence of a George to scream at, his pain turned inward.

“Should I hire a private detective?” he asked us.

“I don’t think he wants to be found,” I said.

I witnessed the most heartbreaking of these attempts to connect on the Christmas about five years ago, on our family’s annual trip to New York to celebrate my parents’ anniversary. Every year my parents revisit the same Upper West Side pizza place, the same Hungarian pastry shop, the same old haunts they’d loved as young adults living in the city. They’d always start their nostalgia tour at the Met museum to see the magnificent, rococo-style tree that gets rolled out once a year. That particular year, my father had made tentative plans with George to meet us there. I remember my father waiting for him patiently, by the tree, as choral music piped hollowly in the background.

“If George showed up on our doorstep today, do you know what I’d say?” my father asked while barbecuing during the summer of 2012. “ ‘Slay the fatted calf!’ ”

The prodigal son did return, eventually. But by then, there was no time left to do anything about it.

In our family narrative, I myself became the prodigal son. I would pull away and come back. I would lash out at the worst times. I would think of myself as not only the enemy of the family—which for 11 years consisted of the twin couplings of my parents and my sister and her ex-husband—but the enemy of the concept of heterosexuality and all it promised. I wanted to be accepted by them, but not on their terms. I wanted to fit in while also retaining my identity. But in our family, so much of identity has to do with who you’re dating, and I was never dating anyone.

When I had to “come out” to my parents in college, I was at a loss for words. Or, not specifically words, but examples. If I had been “just” gay, it would have been simple enough. In fact it would have been expected, anticipated. I could have just pointed to the example of George and said, “A female version of that,” and my parents would have nodded their heads, safe in the knowledge that they had guessed correctly.

I didn’t know about trans history then. I didn’t want to know.

A part of me still doesn’t want to know, a feeling that shames me. What little I had the courage to find out did not make me feel strong or less alone. I knew a few names: Billy Tipton, Marsha P. Johnson, Leslie Feinberg, Lou Sullivan—dead, murdered, dying. These were people I did not, could not identify with. For me, it was like giving up to come out. These weren’t people who made sense to me and, judging from the reaction of the few trans people I’d met, I made no sense to them. Lou Sullivan came the closest. Sullivan had been, it is reported, the “first out transgender man to live as an out gay man.” His stamp of success in this endeavor—tragically—was to have contracted AIDS in the late ’80s. He is quoted, famously, as having said in the Advocate:

Ironically, I have been diagnosed with AIDS, still seen as a gay man’s disease. . . . I took a certain pleasure in informing the gender clinic that even though their program told me I could not live as a gay man, it looks like I’m going to die like one.

He wrote this in an op-ed in 1989, a year after I was born.

You can see why I didn’t want to bring up Lou Sullivan with my parents. Especially my father. To him more than anyone, “gay” meant loss. More than that: it meant kinship, closeness, the beginning of building a world all their own—and then death.

Two years ago, my father got the call from George’s sister saying that George was dying of cancers, plural. He didn’t have a lot of time, but he wanted to reach out to my father. My parents took a trip to Baltimore to be by his side for the last time. A week or so afterward, George died.

When I asked my father what he and George talked about, what excuses he’d given for staying away so long, he just said, “You were right.”

Over the years, my father had asked me why I thought George stopped hanging around him and my mother. I told him what I thought, and apparently, the theories I had presented were exactly what George told him on his deathbed: George felt trapped. He felt judged. He didn’t want to explain himself, he just wanted to go where no one would be looking at him anymore.

Obviously I felt sad for my dad, and for myself. But I must admit that I took some weird comfort in having understood all along. And the things I wanted to say that sprang from those spiteful feelings were the things I did not say: That George was reacting to their perfect, textbook heterosexuality, that I knew what it was like for me when my parents would come together stubbornly on a certain point, as if of one mind, one intolerant, blind heart, and so I knew what it was like for him. No wonder, I thought but did not say. No fucking wonder he left you both.

If I had said those things it would not have been out of cruelty. It would have been to make them understand a thing that was beyond understanding at that point in time, in their lives, in my life, maybe in history itself, except for those who found themselves living somewhere inside the thing beyond conventional understanding. But I didn’t want them to think I would also leave them. I knew a conversation about George, for my parents, was always a conversation about me, even if they didn’t know it. To them, “I’m gay” or “I’m trans” was, in part, a veiled threat: “I’m leaving you.” I didn’t say those things because I didn’t want to intensify the threat.

In another world, who knows: things might have been different. It’s possible that if George were here, then at moments where I wonder what injectable testosterone might have to offer, if it might quiet something in me that won’t shut the fuck up, or if that part of me will always rage and scream no matter what I do, there would be someone on my side. Maybe he did see me and understand me before I had the chance to understand myself. Or maybe not. I never got the chance to find out.

When my father turned 40, he and George and single-bed Lothario Stephen Lynch went on a trip to the Cape to celebrate. One photo from that trip is of my father smiling wide, with George next to him, close-lipped, looking happy yet secretive. When I look at that picture now, I imagine George’s secretiveness as queerness, as a kind of guardian angel ideology seeing me through the blackout years of childhood and puberty. I like to think it can still see me now, when my mother looks over the kitchen island at me and says tenderly, “As hard as it’s been, you’ve never totally pulled away.”