If you were a 70 year old who had lived in Iran all your life, you would not be able to remember a time, except for a brief interlude in the early 1980s, when your country was neither (a) occupied by a foreign power, (b) ruled by the puppet of a foreign power, nor (c) prevented from free trade by the sanctions of a foreign power. That is what comes of being what the British imperialist Lord Curzon called in 1892—even before oil became a strategic issue—one of “the pieces on a chessboard upon which is being played out a game for the dominion of the world”. More than a century later, Iran (Persia as it was in Curzon’s day) is still a piece on the board.

Sun Sets On Empire

Since the late 1940s, Iranians had become increasingly indignant that the British government was getting a bigger share of the country’s oil revenues than Iran itself took in so-called royalties. After elections in 1949 in which this became a prominent issue, an aging firebrand nationalist by the name of Mohammed Mossadegh led a movement to renegotiate the deal and shift the balance closer to the 50:50 other Middle Eastern oil countries were commonly agreeing to. The Brits, who had held the Persian concessions since 1889, were implacably opposed. But by the time they had at last agreed to a sort of fake 50:50 deal, an overwhelming feeling had grown up in the country that Iran ought to own its own oil, and in March 1951 the vote to nationalize was passed in the Iranian parliament (or Majlis). Mossadegh became Prime Minister in April (his more pro-Western predecessor having been assassinated by nationalists the month before).

In response, Britain first imposed an embargo worldwide on Iranian oil, then froze Iran’s assets in the sterling area and banned exports to the country. (It also challenged the nationalization at the International Court of Justice, but the court ruled that it was essentially a commercial dispute and hence outside their jurisdiction). Then it hatched a plot to remove Prime Minister Mossadegh. At which, however, Harry Truman demurred.

Sun Rises On Empire

The history of relations between the U.S. and Iran is not a happy one, either. In 1953, Eisenhower took over from Truman as President. The Brits under Churchill played the old Spread Of Communism card which proved so powerful in the early years of the Cold War—you could get the Americans to do almost anything in the name of countering what came to be called the “Domino Effect”—and Eisenhower gave the nod to an updated plan. There was to be help from some senior members of the army. The young reigning Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, dithered anxiously on the fence for a while but eventually consented. And so the CIA went—bumbled might be a better word—into action. (There is a detailed account of this slightly comic and poorly managed coup in the New York Times archive). When the dust settled, the Shah’s position was consolidated and Iranian oil was now divided up among not only British Petroleum (formerly the Anglo Iranian Oil Company and now BP) but Royal Dutch Shell, Compagnie Française des Pétroles (now Total SA), and five U.S. oil companies.

The U.S.-backed Shah’s reign was a stern one. Mossadegh was put under house arrest. His Foreign Minister, Hussein Fatemi, was executed, and several army officers were also sentenced to death. Hundreds of political opponents were imprisoned. Martial law continued for four years after the coup, hostile political parties were banned, the press was controlled and although there were nominally elections they were a travesty. SAVAK, the secret police trained under a U.S. Army General named H. Norman Schwarzkopf, played a prominent role (or, in the words of the Library of Congress Country Study on Iran “gained notoriety for its excessive zeal in maintaining internal security”). And, to be sure, the Shah had reason to be fearful: in 1965 one of his prime ministers was assassinated and an attempt was made on his own life—not for the first time. Of several groups during that period when guerilla warfare became very fashionable throughout much of the world, the

Fedayan-e Khalq (“People’s Warriors”) and the Mojahedin-e Khalq (“People’s Fighters”) survived SAVAK’s attempts to eliminate them, pulling off attacks on state institutions, foreign diplomatic and commercial offices, and on Iranian security and U.S. military personnel, although a good many of them were killed or imprisoned.

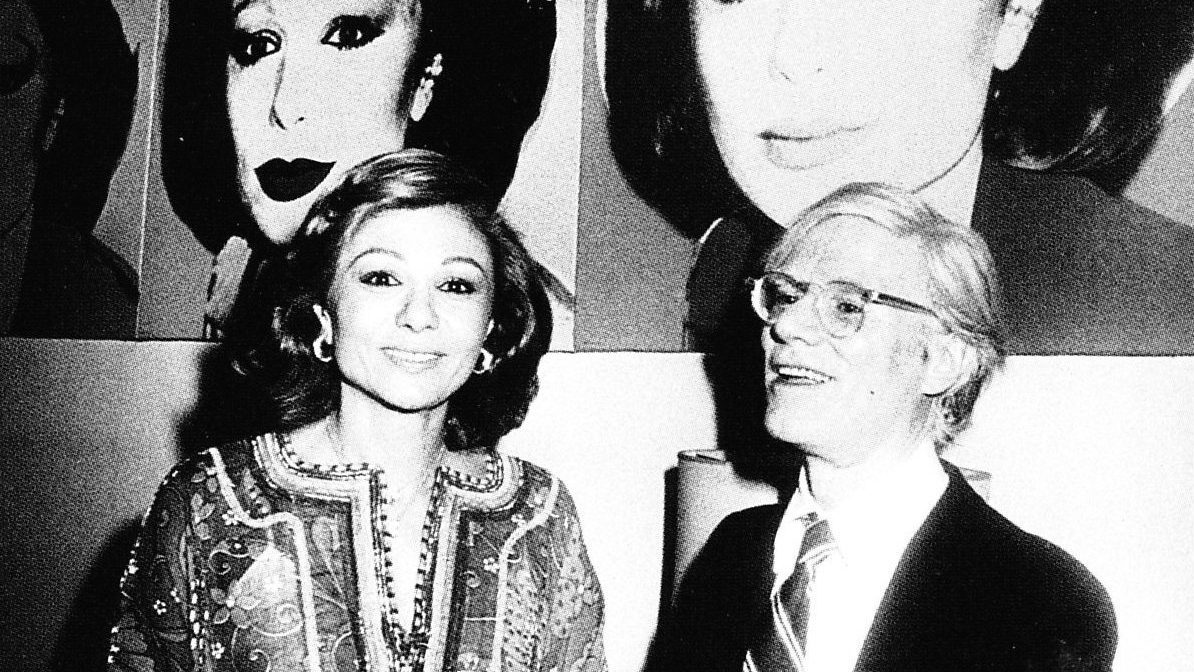

None of this was evident in the image of the Shah in the U.S. He and his third wife, Farah, were cast as a glamorous and sophisticated couple who were bringing a backward country into the modern age. Particularly after the surge in oil prices following the Arab oil embargo of 1973, his wealth increased enormously, attracting flocks of courtiers and sycophants, art dealers and fashion designers.

In a characteristically scathing critique of Andy Warhol, the late art critic Robert Hughes offered this description:

One of the odder aspects of the late Shah’s regime was its wish to buy modern Western art, so as to seem “liberal” and “advanced.” Seurat in the parlor, SAVAK in the basement. The former Shahbanu, Farah Diba, spent millions of dollars exercising this fantasy. Nothing pulls the art world into line faster than the sight of an imperial checkbook […] Dealers started learning Farsi, Iranian fine-arts exchange students who happened to be the sons or daughters of the Tehran gratin acquired a sudden cachet as research assistants, and invitations to the Iranian embassy—not the hottest tickets in town before 1972—were now much coveted.

The main beneficiary of this was Warhol, who became the semi-official portraitist to the Peacock Throne. When the Interview crowd were not at the tub of caviar in the consulate like pigeons around a birdbath, they were on an Air Iran jet somewhere between Kennedy Airport and Tehran.

Like many others in history enriched by good fortune, the Shah also gained a reputation as a leader of extraordinary talent and enlightenment. Nelson Rockefeller compared him to Alexander the Great and suggested “We must take His Imperial Majesty to the United States for a couple of years so that he can teach us how to run a country”.

The Return of the Native

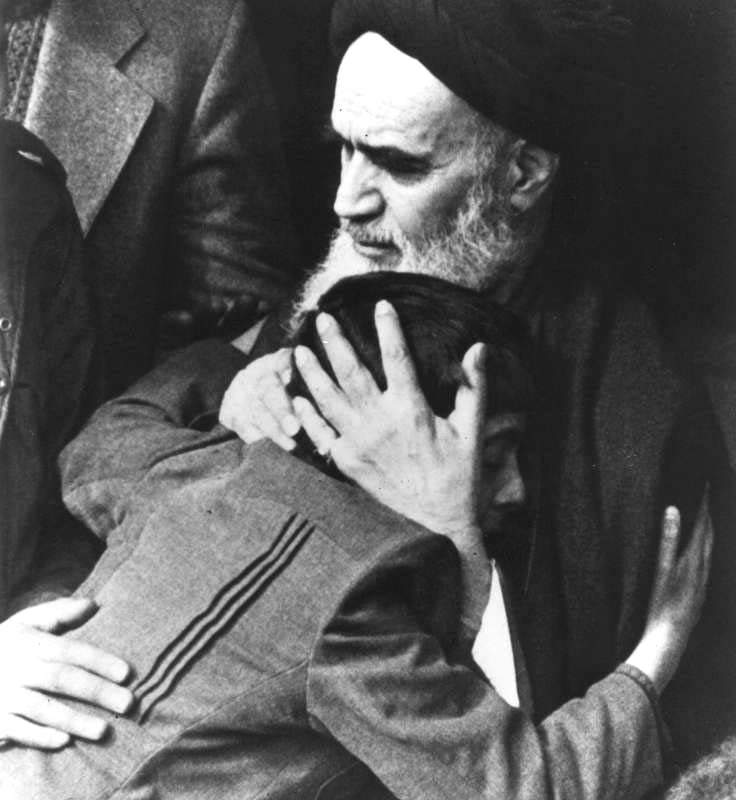

The extent to which anti-U.S. resentment had been suppressed over the 25 years of the Shah’s reign was visible in the massive crowds (estimated by the BBC at five million) which greeted the Ayatollah Khomeini, a stubborn and unrelenting opponent of the Shah, on his return to Iran from exile at the beginning of the February 1979 revolution. The revolution was itself quite brutal, with ad hoc so-called “revolutionary committees” taking control of institutions and businesses, seizing property, and conducting summary trials and executions. Almost daily, former military and police officers, parliamentary deputies, SAVAK agents and other officials of the Shah regime were hanged, shot or otherwise put to death. In April, possibly because he was worried about a counter-coup by an army that had served under the Shah, Khomeini created the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) as a sort of Praetorian Guard for himself and the revolution.

Nine months after Khomeini’s return, President Carter allowed the Shah, terminally ill with cancer, to come from his exile in Mexico to the U.S. for medical treatment. Iranians took this as proof of a counter-revolutionary plot. Students demonstrated the popular anger by storming the U.S. Embassy and, even though it was probably not their original intention, they ended up making hostages of 52 unfortunate Americans, who were held, ultimately, for 444 days.

It is hard to understate the impact of the Iranian revolution on the U.S. position in the Middle East. Iran was second only to Saudi Arabia—generally a reliable U.S. ally—in oil production among OPEC countries, such that the two together produced about 13.5 million barrels of oil per day. That was roughly two-thirds of all Persian Gulf production and 45% of total OPEC output; and U.S. oil companies mediated a substantial proportion of Iran’s exports. Under the Shah Iran was one of the few Muslim countries to recognize Israel, to whom it also sold oil. In Cold War terms it was a frontline state, sharing a border with the Soviet Union of over 1,000 miles, a valuable geography for the CIA, which had listening posts dotted along it. The “loss” of Iran was strategically nothing less than a disaster. A Queen had been knocked off the chessboard.

What? What Did I Do?

For Americans, if the evident hostility of the Iranian public towards them at the beginning of the revolution ignited a spark of surprise and a small fire of indignation, the hostage drama, with its pictures of blindfolded Americans being paraded in front of the crowds and of yelling mobs burning the American flag, was like throwing on buckets of high-octane aviation fuel. Back in the U.S. there were yellow ribbons everywhere, and every day was proclaimed on the evening news as “Day n of the Hostage Crisis”.

One could hardly wish for a more unifying enemy than the Ayatollah Khomeini, a remote, austere, implacable figure, tall and turbanned, with a permanent frown and an almost inhumanly fanatical air unrelieved by the slightest show of mercy towards anyone who could be construed as having been allied with the Pahlavi regime. It did not help that he called for Islamic revolutions throughout the Muslim world, starting with his neighbor Iraq; nor that he labeled the U.S. “the Great Satan”. If there were any bogeyman more likely than Islam to succeed Communism as the potential toppler of dominoes, it is hard to imagine what it might have been; and to this day, the fear of Islam runs like a Khomeini-shaped scar deep in the white-American psyche.

The Empire Strikes Back

Facing likely catastrophe in the elections if he failed to do something, President Carter signed an Executive Order under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 freezing Iranian assets. Other western countries, reportedly with some State Department encouragement, also imposed punitive economic measures. In its 1981 fiscal year, Iran’s oil exports declined to 780,000 barrels a day from around 4.5 million barrels a day in FY 1978. The sanctions were not without downside: The average price of crude oil jumped from about $14 a barrel in 1978 to almost $37 in election-year 1980 (or about $110 in 2017 dollars), and the U.S. went into a deep recession.

Although sanctions were briefly lifted by Ronald Reagan after the release of the hostages in early 1981, Iran has been under U.S. sanctions more or less ever since. Sanctions were increased during the eight-year war between Iran and Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, particularly after the Hezbollah bombing of a U.S. barracks in Lebanon in 1983, which resulted in the deaths of 241 Marines. In 1985, Reagan imposed a ban on importing Iranian oil. Notably, however, and no doubt with an eye to the many members of his cabinet with ties to the oil industry, he did not ban foreign subsidiaries of U.S. oil companies from trading Iranian oil to customers outside the U.S.. It would not do to let European companies like Total take too much of the market just because they didn’t share American popular indignation. While sanctions were nominally in place, there was a certain pragmatic relaxation of tone over the years such that by about 1994 American oil companies had become Iran’s single largest customer, accounting for about $4 billion, or a quarter, of their annual oil exports, and U.S. exports to Iran amounted to $326mm (down from a peak of $748mm in 1992).

For reasons that seem nowhere to have been made explicit, however, anti-Iran rhetoric began to heat up quite markedly under Clinton, whose administration, although it presented no startling new evidence, accused Iran of spending hundreds of millions of dollars annually on international terrorism and of attempting to acquire or build nuclear weapons. (From reading the history, it seems that, according to intelligence sources, Iran has been on the verge of obtaining nuclear weapons for at least the past 25 years).

In February 1994, the administration announced a new “dual containment” policy towards Iran (and Iraq), through a speech by special assistant Martin Indyk, formerly of AIPAC, the best known pro-Israel lobbying group and campaign contributor in Washington, and it is hard not to suspect the hand of Israel more firmly on the tiller of America’s Middle East policy more or less continuously since this time.

Am I Being Targeted By Terrorists?

In July 1994, there was a rash of bombings against Jewish targets, one massive attack with 85 fatalities in Buenos Aires, an explosion on a plane in Panama (a flight on which twelve of the 19 passengers were Jewish) and two relatively minor explosions in London. Although none has ever been conclusively linked to Iran in the decades since, then Israeli Foreign Minister Shimon Peres within a few days proclaimed that “there is no longer the slightest doubt that Iran stands behind the bombings” (in Argentina and the UK). Warren Christopher, Clinton’s Secretary of State, told a House committee: “Groups like Hezbollah that wreak havoc and bloodshed must be defeated. And Hezbollah’s patron, Iran, must be contained.” (Iran, meanwhile, claimed that Israel itself had staged the bombings in Argentina and the UK.) In January 1995, Senator for New York Alfonse D’Amato introduced a bill to impose further sanctions. For the first time, this bill included provisions to effectively extend American law overseas by banning American companies from trading with foreign companies that continued to do business with Iran.

The conflicting interests of the oil industry and the government came into sharp focus in March 1995 when the U.S. oil giant Conoco announced a deal with Iran to develop two huge offshore oilfields near the Straits of Hormuz. This was a step beyond the oil-trading loophole which U.S. companies had exploited so actively, and Clinton quickly put a stop to it. Further, in May, in a speech to the World Jewish Congress at the Waldorf Astoria on Park Avenue, he announced that he would sign an Executive Order imposing a new embargo virtually eliminating U.S. exports to Iran, “paymaster to terrorists”, and forbidding U.S. oil companies from handling more than 20% of Iranian oil exports. Clinton pressed allies to join in the ban, but without success. In fact, exactly as the U.S. oil industry had feared, French oil company Total snapped up the deal which Conoco had been forced to drop, for $600mm, the largest of its kind ever at the time.

In July 1996, a bomb at Atlanta Centennial Olympic Park and the crash of TWA Flight 800 off Long Island reawoke American unease. Once again, foreign terrorism was suspected, although the Atlanta incident proved to be the work of an anti-abortion crank and the TWA crash was later attributed to an accidental electrical spark in one of the plane’s fuel tanks. The TWA incident, in particular, boosted passage of the Iran and Libya Sanctions bill in Congress and in August Clinton signed it into law. While watered down from the original D’Amato draft, the Iran and Libya Sanctions Act of 1996 still provided for sanctions on foreign companies investing in petroleum development in Iran.

“Now the nations of the world will know they can trade with them or trade with us. They have to choose,” said Senator D’Amato when the bill was passed.

As the Middle East analyst Juan Cole has noted, however, in casting doubt on the effectiveness of sanctions:

It is odd that the politicians in Washington, who are always loudly proclaiming their belief in the market, think its iron laws can be suspended by a simple vote on their parts

The Lone Sanctioneer

Many U.S. allies regarded ILSA as an attempt by the U.S. to impose its laws extraterritorially and reacted with some indignation. In November, the EU passed a so-called “Blocking Statute” which was intended to protect EU companies from U.S. court rulings resulting from ILSA. The EU also challenged the U.S. at the World Trade Organization. That left the U.S. as the lone sanctioneer.

In fact, the sanctions available under ILSA were not much of a deterrent in any case, despite Senator D’Amato’s truculent statement to the contrary, and some pundits have speculated that Clinton signed it only with an eye on the presidential elections two months ahead. In any event, Clinton backed down after the election, and in April 1997, the EU and U.S. reached an understanding the practical effect of which was that the blocking statute was never tested and the unilateral sanctions were tacitly admitted to be a failure.

There was some softening of the mutual hostility between the U.S. and Iran after the surprise election of a more reformist President, Mohammad Khatami, in Iran in 1997. Most sanctions remained nominally in place, although, in an Orientalist-tinted gesture of goodwill, President Clinton lifted prohibitions on carpets and pistachios, among a few other items (not including oil), as well as permitting the export to Iran of badly needed spare parts for its aging Boeings. In May 1998, he waived sanctions on Total, Gazprom and a Malaysian oil company, which had together signed a $2bn deal with Iran to expand its offshore oil activities. In March 2000, Secretary of State Madeleine Albright also officially apologized to Iran for the CIA’s decisive role in the 1953 coup, though without offering any reparation.

Old Fashioned Diplomacy

The failure of unilateral sanctions by the U.S. as a policy weapon was highlighted again late in 2003 when threats by the George W. Bush administration failed to deter Iran from continuing its recently discovered uranium enrichment activities. It was not until a group of European countries (France, Britain and Germany) stepped in that an accord was finally reached, culminating in the Paris Agreement signed in November 2004, whereby Iran agreed to stop enrichment and to allow increased inspection by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

Notably, it was the threat of multilateral sanctions, including by Europe and the UN, coupled with a more respectful and less confrontational approach, that brought Iran to agreement. The chief Iranian negotiator in this agreement was a mid-level cleric by the name of Hassan Rouhani, who later became President of Iran, a champion of reform and on the Iranian side the man most responsible for finally bringing about a rapprochement, albeit one that has proved to be short lived.

Part of the problem in dealing with Iran has been the internal schism between so-called “hardliners”, such as the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) and “reformists” like Khatami. The IRGC has over the years built up a position of formidable power not only in the military but also in the social, political and especially the economic spheres. Given this position in the catbird seat, it has been loath to encourage any change in the status quo and so is inherently against reform.

After the election of hardliner Mahmoud Ahmadinejad to the presidency in 2005, the power of the IRGC increased dramatically and relations with the U.S. and Europe took a distinct turn for the worse. Ahmadinejad accused the Iranian diplomats who had negotiated the Paris Agreement of treason and restarted uranium enrichment. The Bush administration managed to get several resolutions passed at the UN, but could not rally support for the kind of broad sanctions that might significantly sap Iran’s economy. Late in 2007, the U.S. Director of National Intelligence released a report whose surprising conclusions included that Iran had effectively complied with its obligations under the Paris Agreement. This took the wind out of the administration’s sails with respect to passing more sweeping sanctions.

For as long as Ahmadinejad was president, however, Iranians were destined to suffer further. His defiance paid off to the extent that in June 2008 the U.S. together with China, France, Germany, Russia, the UK and the EU approached Iran with proposals to improve relations in exchange for stabilization of the uranium enrichment program – in effect, a concession for the first time that Iran had a legitimate right to develop nuclear energy for peaceful purposes. By 2010 Iran had begun making enriched uranium of a quality (20% U 235) which put it well along the path towards weapons-grade production, and alarming the west enough to reawaken talk of coordinated sanctions. The U.S., always in the vanguard, in July 2010 passed the Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability and Divestment Act (CISADA) which supplemented sanctions under ILSA and severely limited the access of many Iranian banks to the international banking system. Again, however, the potential extraterritorial overreach aroused distinct resentment in the EU.

Just as in the days of the Clinton and George W. Bush administrations, these unilateral sanctions were notably ineffectual. It was eighteen months, before, in January 2012, the EU joined in imposing sanctions with an embargo on importing Iranian oil. After considerable behind-the-scenes negotiations, SWIFT, the Belgium-based secure messaging system which forms the communications backbone of international banking, disconnected 30 Iranian banks from its network, thereby largely cutting Iran off from international trade and payments. The impact on the Iranian economy was such that, by 2013 when Ahmadenijad’s second (and therefore final) term ended, the reformist cleric Hassan Rouhani, still fiercely opposed by the hardliners, won an easy and popular victory in the elections for a new president.

Rouhani’s accession immediately cleared the path for an agreement. It was not a smooth path, partly because of ferocious opposition by Israel’s president Netanyahu and the U.S. Congress, not to mention opposition by Iranian hardliners, but it eventually led to the July 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) between Iran and the so-called P5+1 (China, France, Germany, Russia, the UK, and the U.S.) as well as with the EU. With the suspension of sanctions, Iran’s economy came bouncing back.

Making America Great Again

Unfortunately for our 70-year-old Iranian and his 82 million long-suffering compatriots, in 2016 the U.S. elected a President who was, to say the least, antagonistic towards the JCPOA. In May 2018 he unilaterally slithered out of the agreement by refusing, without grounds, to certify that Iran was complying with its terms. He announced the phased resumption of sanctions, whose full effect came into force this past week. The other parties—the European signatories as well as China and Russia—remain committed and have been trying to create ways for Iran to continue trading. Widespread fear of U.S. retaliation among non-U.S. businesses and banks has, however, made this difficult. SWIFT has already agreed to bow down.

Trump’s unofficial national security advisor, John Bolton, who resembles the old Ayatollah Khomeini in his fanaticism (and in the luxuriance, if not the exact design, of his facial hair), proclaimed in an echo of Alfonse D’Amato more than 20 years before:

“We expect that Europeans will see, as businesses all over Europe are seeing, that the choice between doing business with Iran or doing business with the United States is very clear to them.”

It remains to be seen whether unilateral sanctions will succeed where they have previously failed. Already one small crack has appeared: Fearing another spike in oil prices, Trump, on the day sanctions were to resume, announced waivers for eight countries dependent on Iran for their oil imports.

Iran has had its share of troubles over the past couple of millenia. It survived Alexander the Great. It survived Genghis Khan. And in between, as Edward Gibbon noted, it survived the Romans:

The government and religion of Persia have deserved some notice, from their connection with the decline and fall of the Roman empire.

Oliver Corlett, Oeconoclast