The Gabriela Mistral museum in Vicuña, Chile, doesn’t give you much. Not because everything is in Spanish: people in Chile tend to read Spanish quite well, it will interest you to learn. Though it is worth noting that the museum is aimed at Spanish-speakers, at Chileans, among whom Gabriela Mistral’s fame now primarily resides (and where her name can be found on a school, an avenue, or a library in any city). She is as familiar in Chile as the 5000 peso note, on which her face can be found.

It wasn’t always so: in her lifetime, she was globally famous, because she lived from her twenties until her death outside of Chile, only returning three times. She was the kind of poet who would be the first Latin American to win the Nobel Prize for Literature: a poet who wrote about Chile, yes, but who did it in the great capitals of Europe and the Americas, a diplomat and an educator and a living symbol of a country she had left forever. If she always insisted that her poetry was rooted in the stark beauty of her native Valle del Elqui—and you will find her insisting that, repeatedly, in the museum—she only really came home after her death from pancreatic cancer in 1957.

The Valle del Elqui region is beautiful, if you want to use that word. It’s stark, dry, hot, and barren, except for the rich abundance that flows out of its irrigated vineyards, grapes famously used to make Pisco. The mountains are not high by the standards of mountains, but they crowd you close; they remind me of Appalachia, where the world can seem to compress so claustrophobically until the only way you can find it beautiful is to leave.

If you can’t read Spanish, the museum in Vicuña doesn’t have much for you. It’s free to enter; you can sit in its courtyards and feel the breeze, and you can walk freely into the little library which—judging from all the non-Mistral volumes

—seems to function as exactly that, a little rural library in a little rural town. It’s a restful, gentle place; we sat for a long time in a little courtyard, feeling the sun and the breeze. A group of children on a school trip occupied the other end of the courtyard, their chattering somehow swallowed up by the wind.

It’s mainly a museum of words, however, Gabriela Mistral’s words. Scattered throughout are objects of importance to her life, furniture, and photographs; there are collections of her books, which are interesting to look at, and she is, herself, an interesting person to look at. But most of the museum is just careful collections of her words, words from her poetry, from her letters, from her speeches, and from her diaries, and only her words. Indeed, the extent to which she goes un-narrated is striking; there is, in the back corner (next to the TV playing, on repeat, a series of images from her life against a stirring piano-and-guitar soundtrack) a timeline of the events in her life, and this is written from a perspective that regards her in the third person. But other than that, there are very few words about her, very little attempt to explain, or contextualize, or narrate her. In sharp contrast to the kinds of imperatives that patriotic familiarity breeds, the museum is the kind of place you can wander into without ever being told why you are there.

I don’t know who made that decision, or why; I don’t know if that’s a decision that was made when the museum was re-modeled in 2010, when Michelle Bachelet—Chile’s first female president—was finishing her first term, though both the museum and Vicuña itself were much modernized in that era; my companion had been her ten years ago, and found everything quietly but bafflingly different. But it’s no surprise that decisions made in the 20th century about how to represent her, here, gave way to a different set of decisions when became a different kind of national symbol for a very different kind of president. Things, after all, had happened in the interim: a museum that was inaugurated in 1971, when Salvador Allende was president of Chile, would find itself operating under a dictatorship that would, among other things, deny Mistral’s heir and executor the right to publish her papers unless she first relinquished the rights to the Chilean state, and due in part to that, these papers were not published until the 2000s. More to the point, Mistral would prove to be a useful figure for a very conservative sense of proper femininity; if there was something strange, something queer about her in her lifetime—que rara! one might say about her, this striking, un-married childless poet who wrote endlessly about motherhood—she came to stand as a figure of national sentimentalism as the century wore on, far less radical relative to the world as it had become. For a reactionary in the 1970s and 80s, she could be seen (as Nicola Miller put it) as “a conservative woman who dismissed the issue of women’s rights, sanctified motherhood, and remained content to operate within the precepts of the patriarchal state.” And if that wasn’t quit fair, it wasn’t quite wrong either.

In the early 2000s, by contrast, it became much easier to see her as a lesbian poet, living out her life in exile and the closet. Chile had officially transitioned to democracy in 1990, but Pinochet remained commander in chief of the armed forces until 1998, when he was arrested in London; this fact is at least metaphorical for the way that, in the early 2000s, a variety of new-old stories about Chile’s 20th century began coming out, like the long-rumored facts about Mistral’s sexuality.

I find it very hard to read her letters to Doris Dana and not see their relationship as self-evident (and were they letters from a man to a woman or a woman to a man, no one ever would).

In the absence of those letters, it was possible to narrate her childless, unmarried life of service to Chile as a kind of monastic diversion of her natural feminine reproductive energies away from her own family—since she had none—to become a kind of mother for Chile itself. Diamela Eltit called her “a uterus birthing children for the motherland”; her life of feminine service was virgin and maternal, Christian in ways that would be instantly legible and un-challenging to the story of an Opus Dei state: instead of communist and atheist like Pablo Neruda, Gabriela Mistral was someone you could put on the five-thousand peso note.

(In her journals and letters, she says scathing things about Chile, and how it treated her. In her private writing, you read the words of a woman freed to say what she thought about the nation she had left, and to which she would never return, and which paid her salary and upkeep her entire life.)

But even after the letters she sent to Doris Dana were finally published, Gabriela Mistral’s queerness remains contested, a contention or an allegation that “some have said,” but which “no one can say for sure,” and so on. It may simply be that the Gabriela Mistral who was established and mythologized, in the absence of those letters, is the one that people want to read. And, of course, both she and Doris Dana denied that their relationship had been anything of the sort, albeit in the kinds of denials that convince no one. If you want to pick and choose one Gabriela Mistral over the others, you can pick the one who said one thing and use that to forget about the Gabriel Mistral who said other things; you can choose one complete story (secular nun, closeted lesbian) and let its completeness blot out the others.

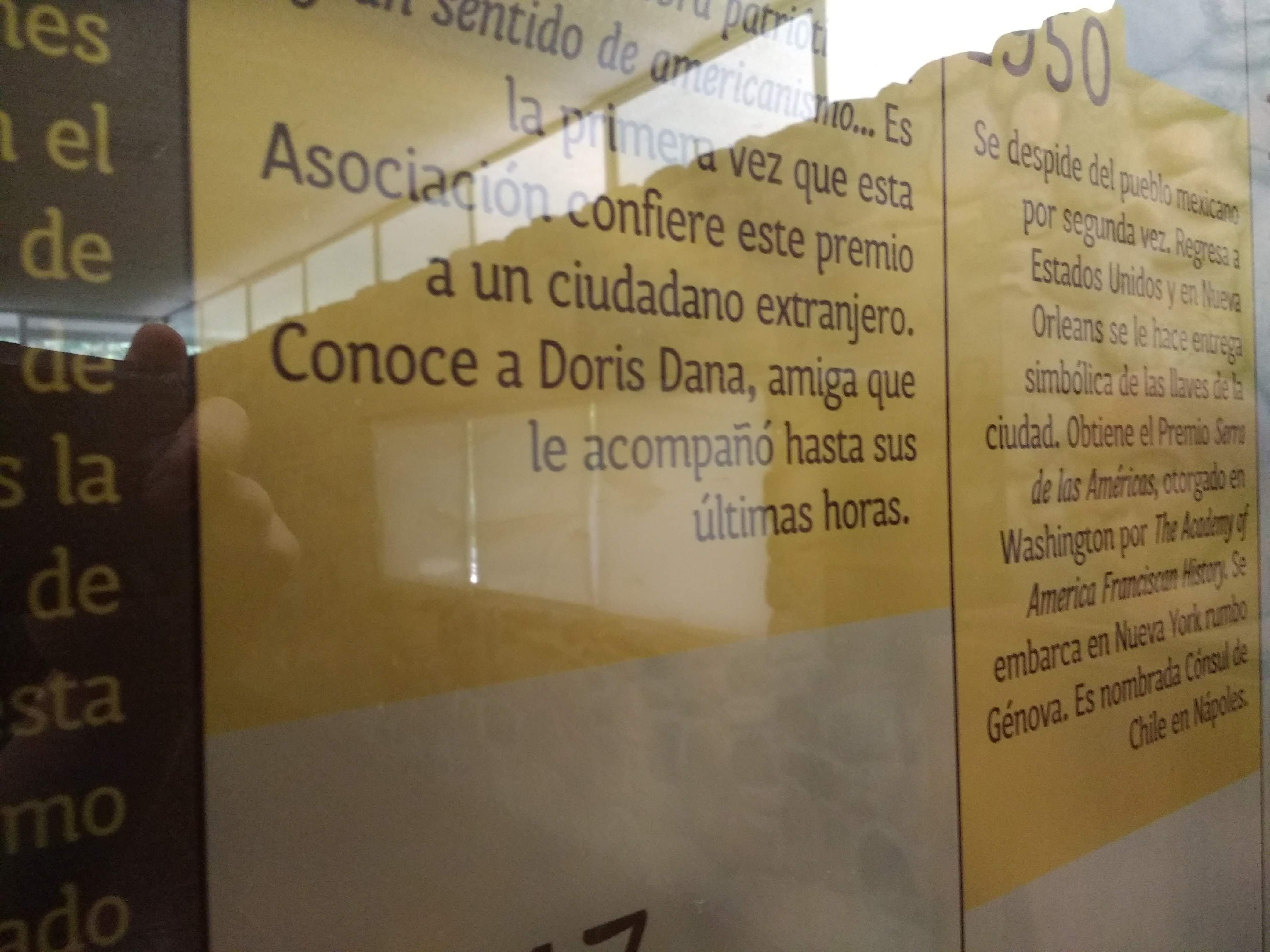

The museum doesn’t pick and choose, because the museum refuses to narrate her; the closest it comes to talking about her is in describing the timeline of her life, in which, for example, it describes meeting Doris Dana, the “amiga” who accompanied her until the end of her life.

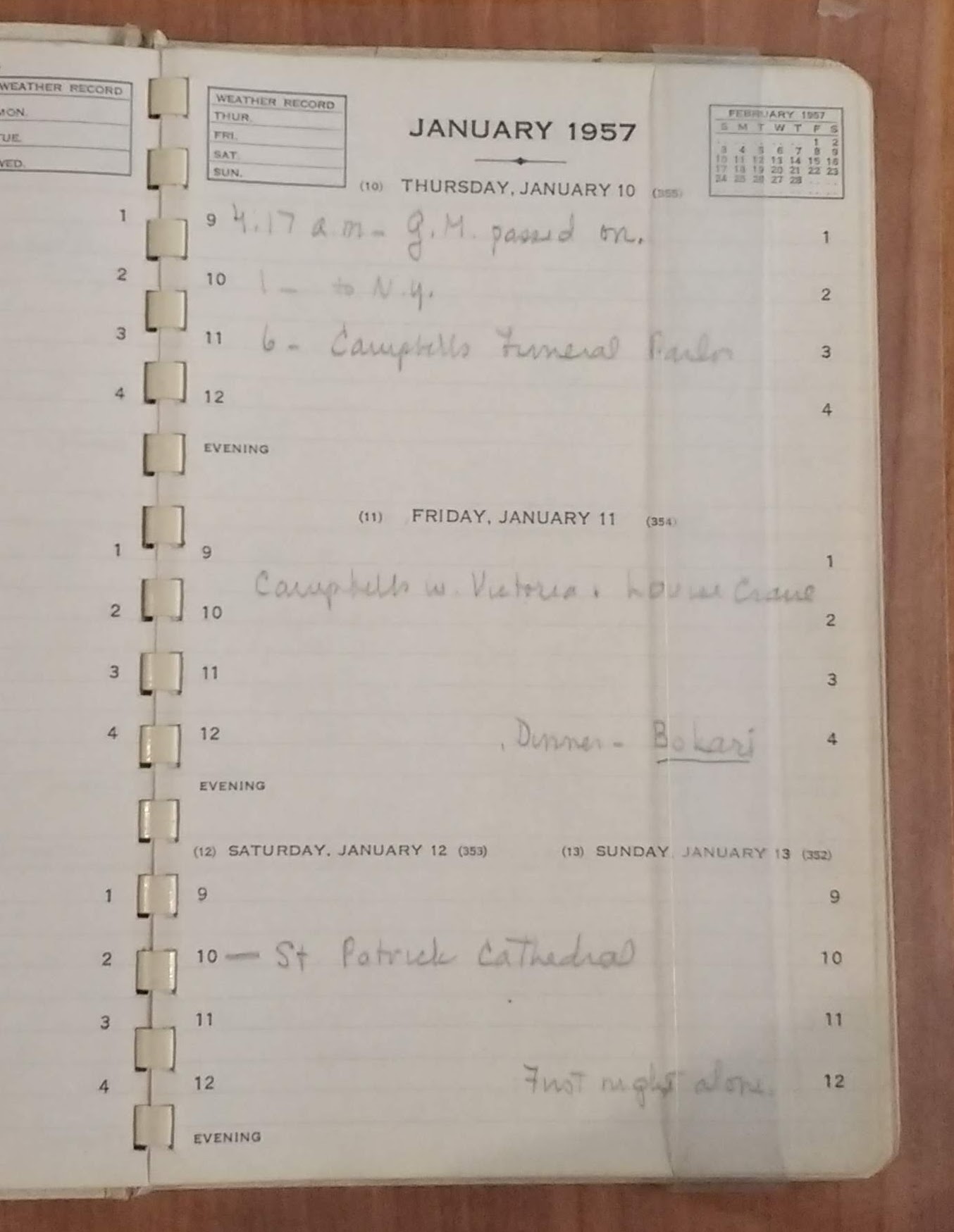

“Amiga” is certainly one way to put it. Another would be the page of Doris Dana’s diary for the three days after Gabriela Mistral died, a page which begins at 4:17 a.m. on Jan 10th with the simple words “G.M. passed on” and ends, on Jan 12th, with the words “First night alone.”

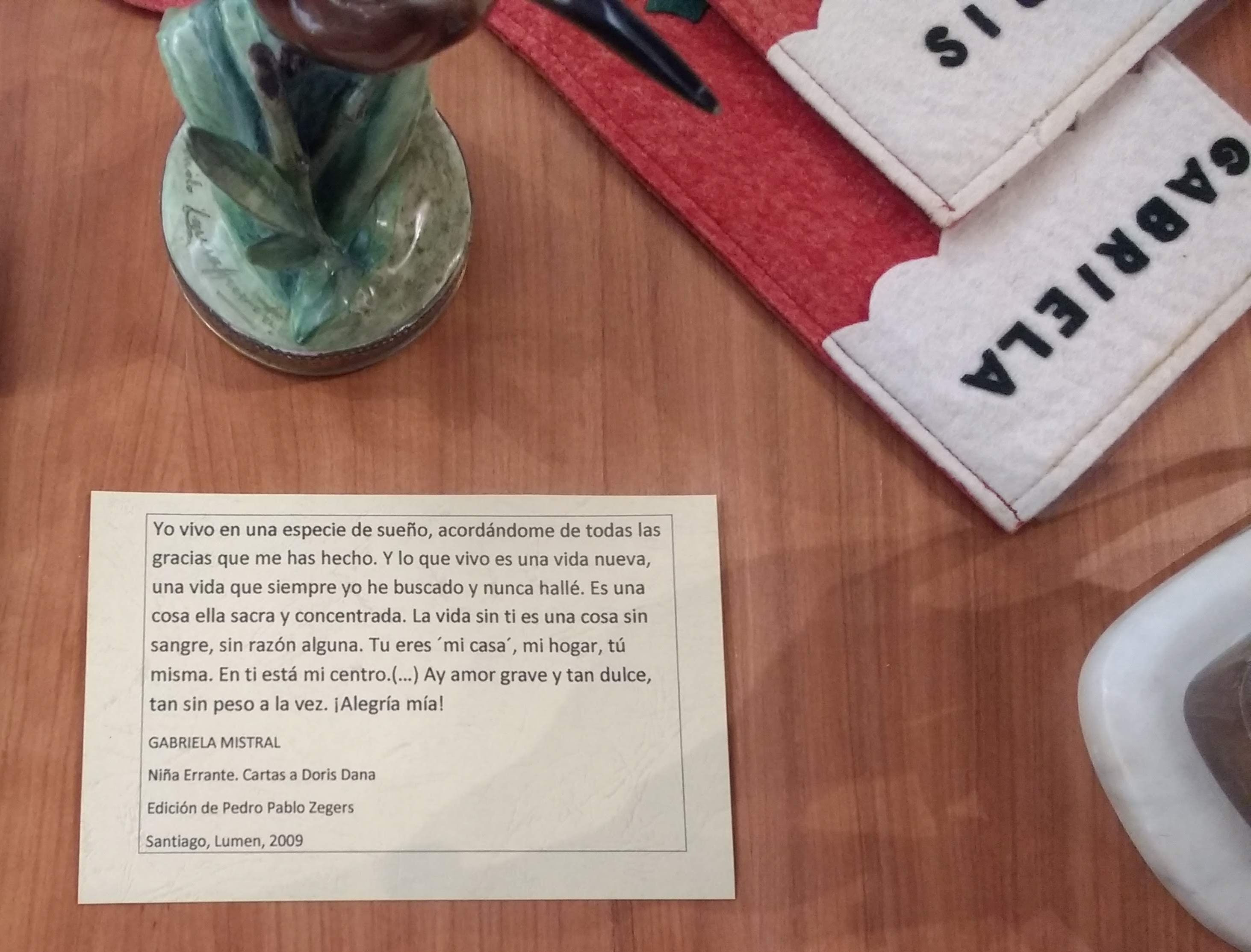

Mistral complained a great deal that Dana didn’t say more; Mistral was a great letter-writer and Dana simply was not; whatever else was true of their relationship, this imbalance in loquacity was a real disagreement. Mistral was more likely to write things like this:

(I live in a kind of dream, remembering all the blessings you’ve brought me. And I now have a new life, one I’d always searched for but had never found. It’s sacred and rich. Life without you is meaningless, absolutely pointless. You’re “my house,” my home, you yourself. My center is within you … Oh, a love deep and so sweet, and so light. My joy!)

If this isn’t sexual love, then of what use is sex? This is love, if anything is.

But as you pick your way through these words and these objects, as a sense of her presence accumulates, I don’t think you get a clearer sense of her, or solve whatever mysteries there might be of her life to solve. If she was queer, and she was, her queerness wasn’t something to clarify or understand or pronounce upon; it wasn’t, and isn’t, something that a museum could explore. And, so, it does not.

What no one would deny about Gabriela Mistral is that she was a woman born in rural Chile in 1889. She lived her life hemmed in by powerful social forces, as stern and omnipresent as the hills of Valle de Elqui; like the people of that region, she learned to live there, to make life and beauty in the places where she could find the room. If she thrived, she did so on those terms, and like those cunning fields and terraces and systems of irrigation, she makes no sense as a person if you remove her from the place that made them necessary. To regard her in the 1970s, the 2000’s, or 2018 as if she could live in these times and still be the person she was then—was she a lesbian? Was she a feminist? Was she conservative?—would be a little like building terraces for pisco grapes anywhere but on those hills. Wine has terroir, and so do poets.

There are many stories that can be told—that have been told

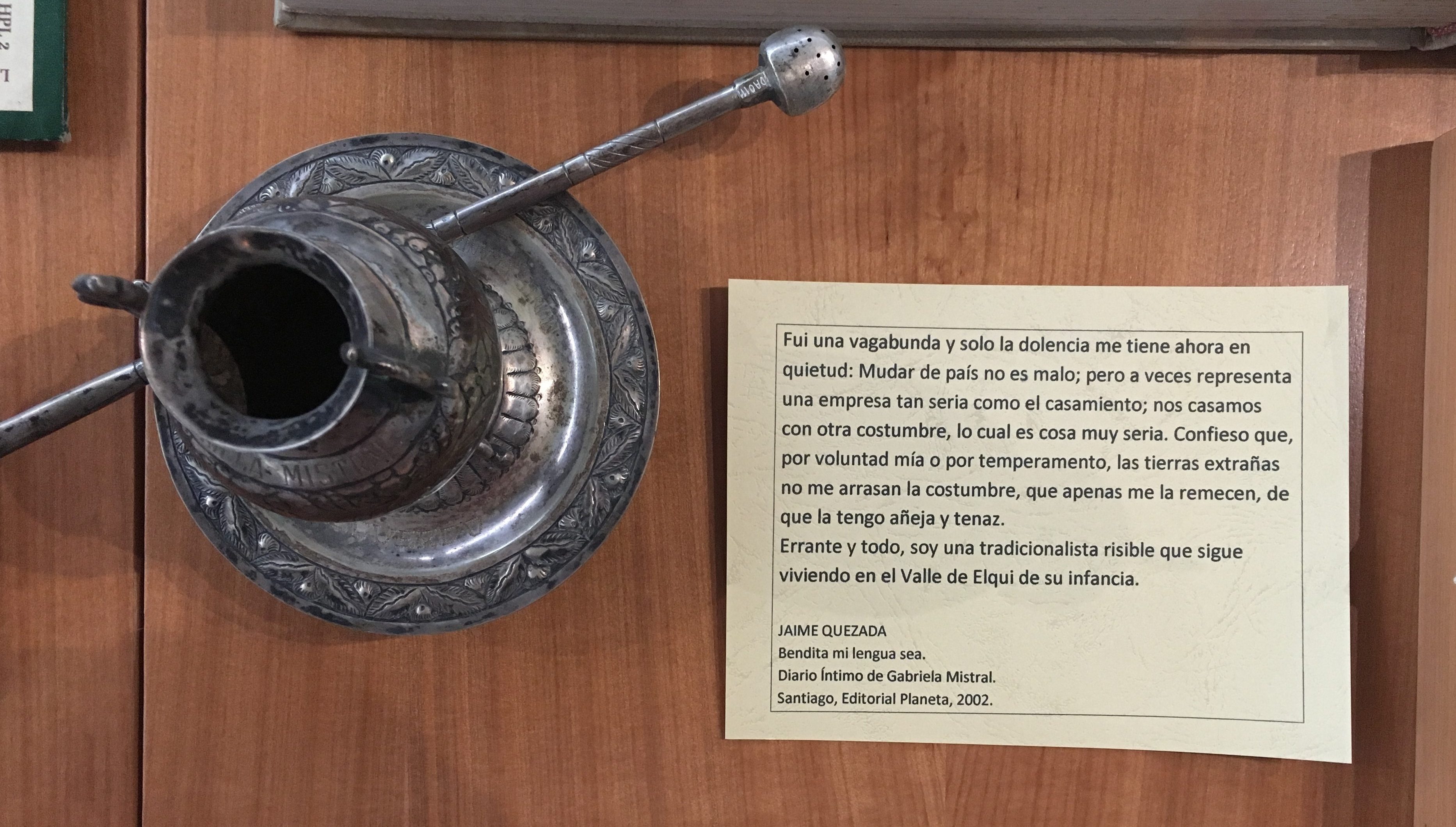

—about Gabriela Mistral, but this is not a museum that gives you a choice, and lets you choose among these stories as you please. None of them are quite there, none of the confident narrations or frames that the twentieth century hung on her name. Instead, it’s a museum filled with silence and omissions; it’s a museum that makes you look for connections—to deduce why there is a mate sitting there amidst photographs, until you see the photograph of her holding it—and to do the same with the pair of Christmas stockings with the names “Doris” and “Gabriel.” You find yourself looking for her words to explain these objects, because objects don’t talk; if this is a museum filled with objects, you will find yourself stymied by their wordless-ness. But it isn’t. It’s filled with words, hers. It’s a library. It’s a school. It’s a resting place. It’s a memory of a home that was never home except in memory.