About a year ago, my mother had just won the Democratic primary race for city council in Annapolis. She was now in the middle of her general election campaign and had been the target of a series of investigations and accusations. Her opposition launched an anonymous letter-writing campaign with the aim of bringing my mother’s past to the public’s attention.

In 2011, new to Annapolis, she had shoplifted a pair of sunglasses from a store. Her mother had just died. She had been drinking for the first time in a long time. She returned the sunglasses, was arrested, paid her fines, performed community service, and had the records expunged. The same thing happened once more in Baltimore, at a grocery store, not long after. The paper’s report contains a scan of the police write-up, where you can read each item my mother stole in plain detail, the ghost of her wandering through the aisles, picking up Kit Kats, gum, peanut butter. It’s all public knowledge now, printed in the Capital Gazette.

Though Annapolis is the capital of Maryland, it’s a small city of not even 40,000 people. My mother’s district, where she ran for city council, is small. She owns an inn there. News travels fast, from pastel house to pastel house, and each dog-walker in between. My mom moved there six years ago, in the aftermath of her divorce from my father and her ongoing, active recovery as an alcoholic.

My family is not estranged, but there are moments when we feel as such. My mother is healthy, but I worry for her every day. She is a quick thinker, curious, immensely energetic. If there is an intended audience for Mary Oliver’s often-anthologized poem “Wild Geese,” which begins, “You do not have to be good. / You do not have to walk on your knees / For a hundred miles through the desert,” I imagine it as my mother, sitting in the first floor of her inn, waiting for the day’s inhabitants. She is beautiful, the skin of her face pulled snare-drum tight around sharp bones. She has a scar on her ankle from where she fell from a steel beam while working construction in her past life, snapping the bone in two.

After the second incident was reported, my mother made a statement acknowledging her use of alcohol. I had reached out to her to make sure she was handling the news in a way that was healthy; her voice broke at times over the phone.

“These people go to church,” I told her, “but they’re mean.”

I went to a bar the night of one of these conversations, drank too much beer and watched bad football, and later sat up in bed and hammered out a long op-ed to the local paper, trying to convince all these people I had never met to love my mother. The next morning, when I received a call from the editor rejecting it, I thought about how I should’ve known no paper would ever run a piece so biased and so full of sorrow.

In hindsight, my mother says, she should have “come out ahead of the story” and disclosed these incidents before the race began. But she was ashamed. And then there was the fact that she was already years forward in her recovery. Expunging the matter after having paid for the crimes made it feel like she had closed a door on the past, allowing her to carry on with her life, her family, whatever future she planned for herself. But any alcoholic will tell you that recovery is a process that is never finished.

A year before all of this we’d sat in the alcove of an Annapolis restaurant on a bright and crisp afternoon, and she told me about her candidacy. I smiled and hugged her, all the while worried that her alcoholism might become a factor. In New York City, local elections can get heated and violent and ruthless. When Khader El-Yateem, a Palestinian American pastor, ran in the primary race for city council in Queens last year, an opponent called him a “Palestinian cleric.” People phoned his house and threatened to kill his family. I guess I thought that Annapolis, small and quiet, seemed safer for her. She was running to win only hundreds of votes, not thousands, not millions. I thought no one would care.

But in time the news of my mother’s crimes came out, and I made the mistake of scrolling down to the comments in the paper. Someone named Be Yourself wrote, “Well ELLY….you must be the first person in history to suffer at with a bad marriage, most, do not steal or lie, cheat to get a seat in government, drink their brains to mush. There are far too many ‘excuses’ being made. Pull up your big girl pants and stop acting like a child.” I read it and cried.

I realized I’d spent much of my childhood doing the same thing to her, judging and accusing, silently blaming her for the dissolution of our family, retreating deeper into myself. But I never thought she would face this from strangers.

Her voice was shaky when I phoned her. She had spoken to the incumbent Democratic councilman, whom she had defeated months before in the primary, asking him if he thought she should withdraw from the race. It felt like too much to go through, she said, that her life had opened up for public view, that she might not be ready. He told her not to withdraw. In the following days, a relatively new PAC began to mail fliers to all of the ward’s residents. Some had a photograph of my mother next to a definition of the word kleptomaniac. Others defined my mother’s “Five Stages of Sunglass Grief,” making a mockery of her divorce and reliance on alcohol.

Her Republican opponent had a hit-and-run expunged from his record, but somehow no one was talking about this, while headlines and hashtags called my mother a shoplifter, a criminal. What had “expunging” meant, when she would pay for the crime again in the future?

I don’t blame anyone for forgiving or not forgiving whomever they choose. I grew up Catholic, so the notion of forgiveness as a unilaterally good thing was ingrained in me at an early age, though eventually I came to see that guilt can be harmful. How can we ask others to participate in some sort of unanimous forgiveness when we are, because of our own guilt, forever asking to be forgiven?

I say all of this because my instinctual reaction to my mother’s situation was to demand that people I’d never met simply be more kind, that they both understand and forgive my mother. I wanted them to have another story to latch on to, to be there over a decade ago when I saw the consequences of her alcoholism firsthand, the long drives with my father through the night to find her in a parking lot, and then to be there later, when she committed to recover.

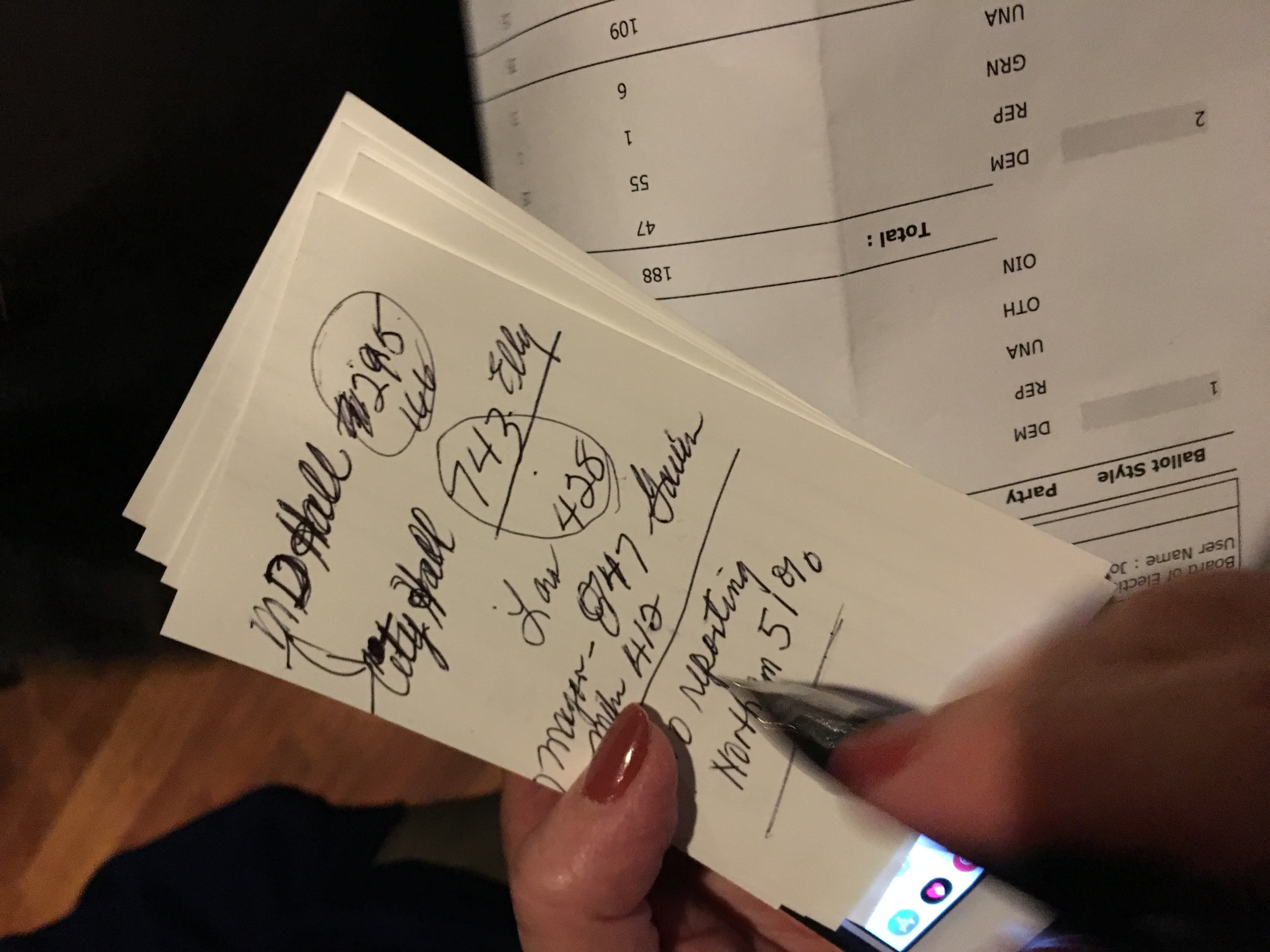

It’s been almost a year since I took the train back to New York City from Annapolis the morning after Election Day. After all of this, the articles and the accusations and the name-calling and the vicious comments, my mother won with little drama, carrying 64 percent of the vote, nearly two out of every three people. My stepdad, brother, I all hugged her, and felt proud and relieved and joyous all at once.

As the night’s festivities wore on—the Democrats had won the mayor’s seat and nearly every city council seat—I couldn’t help but think how many of her constituents will never forgive her. They will most likely never let her forget an action that she has tried, in ways almost only I know, to grow from and hold herself responsible for, the same way she moved with such grace from the tragedy of our early years as a family into a place where she could make both herself and our family better, even if that meant being separated.

On election night, after we left the mayor’s party, my mother, stepdad, brother, and I went to a local diner on one of the small main drags of Annapolis. It was late and they were about to close, but my mother was radiant, and we were hungry. She ordered a decaf coffee and a waffle. She still could not believe it: the margin of victory, the victory itself. There was in her a slight trembling, like water shimmering and shivering in a glass you set down a touch harder than lightly. She had written a speech for the occasion and never got the chance to give it. She pulled the paper out, though, and began to read, as the waitstaff was stacking the day’s pots and pans and the lights along the street outside turned off one by one. I tried to listen, and caught words like concert and symphony, but I couldn’t focus on the whole thing. I was watching her, how she gripped the paper tightly, as if it might somehow fly away and render the whole thing meaningless. Her voice was small and determined. The three of us, her audience, already knew the whole story, its arc and narrative. I don’t think she cared. In her mind, I know, she was already talking to a crowd.

Devin Kelly