A version of this article appeared in The Daily Times, Malawi, Monday, September 5, 2005; reprinted by permission of the author.

When I took over the Stewardship of The Times from Peter Langford, as the paper’s first Malawian Managing Editor in 1971, I was 27 years old, with four years’ experience as the paper’s Sub-Editor and Chief Reporter, and armed with a diploma in journalism from Training in Cardiff, Wales. My Deputy Editor was Levison Lifikilo, who also doubled as Sports Editor after doing sterling work on the Sports Desk of the paper.

On December 31, 1973, The Daily Times became Malawi’s first daily newspaper. I was driven by a burning ambition to turn the broadsheet into a lively, daily tabloid, but without the garish features of the British tabloids. I wanted a paper that would truly reflect the lives and voices of the people, especially of ordinary Malawians in townships like Ndirande, Kanjedza, Chilomoni, Zingwagwa and Kawale.

But that was not to be. While the owners and managers of the company agreed to my suggestions to transform the paper into a tabloid, they were afraid that its editorial content would go against the political grain. What I did not know then was that they had reached agreement with Dr. Banda to purchase the printing company and the newspaper, after high-level secret negotiations.

Production of the newspaper was fraught with technical difficulties. The paper carried very little colour, except on very special editions; pictures were difficult to produce and the printing presses often broke down. It was not unusual for the works manager to phone me at two in the morning to ask what to do because the presses had broken down again. It was a far cry from the bright, colourful and lively papers of today. These are reflecting the traditional role of the press in a democratic society: to enable citizens to exercise their right to know and to freedom of expression.

KISSING NOT ALLOWED

Life in the 70s was a matter of persecution and perseverance for journalists. The same could be said of intellectuals at the University of Malawi, or of any other persons whose sensitive professional activities were kept under constant surveillance by the police and other intelligence organisations of the state. They did this for up to 30 years.

There was no room for dissent. Men were not allowed to grow beards or to keep their hair long and women were ordered to wear clothing that completely covered their knees. Kissing was not allowed in public, or to be shown at the movie, and reports that were critical of Kamuzu and his Government were blacked out with ink or completely ripped out of pages of imported publications that were usually banned altogether by a Censorship Board. The Rhodesian Herald was banned from circulation or importation to Malawi. “Your Kamuzu knows best” was Dr. Banda’s mantra and it was expected of the press to echo this.

In 1973, the political temperature was rising. People were disappearing and Dr. Banda was regularly berating expatriates and demanding that they not interfere in the internal affairs of the country. Diplomatic representatives of Western governments, including the British and Americans, showed little inclination to intervene over declining human rights standards. In any case, Dr. Banda often declared that Westerners who did not like the way he was doing things should pack up and go back where they came from. Malawi, as he put it, was now a sovereign state, and no longer anybody’s colony. Foreigners who criticised him or his government were deported. Many Malawians fled into exile in Zambia and Tanzania. Many were picked up by the Special Branch of the police and thrown into detention camps at Dzaleka in Dowa and Mikuyu in Zomba, after being denounced as dissidents by Dr. Banda.

FOURTH-CLASS JOURNALISTS

Dr. Banda had a love-hate relationship with the press. On the one hand, he detested being described by the Western press as “The Odd Man Out in Africa” because of his dealings with South Africa, which was under apartheid, a system that separated the races under white supremacist rule. He often referred to reporters who criticised his iron-fisted rule as “cheap, fourth-class journalists.” But on the other, he needed the Western press to project him as a credible leader who put the economic interests of his people first, and as a bulwark against Communism and its watered-down version, Socialism, which other leaders were experimenting with on the continent and in the region.

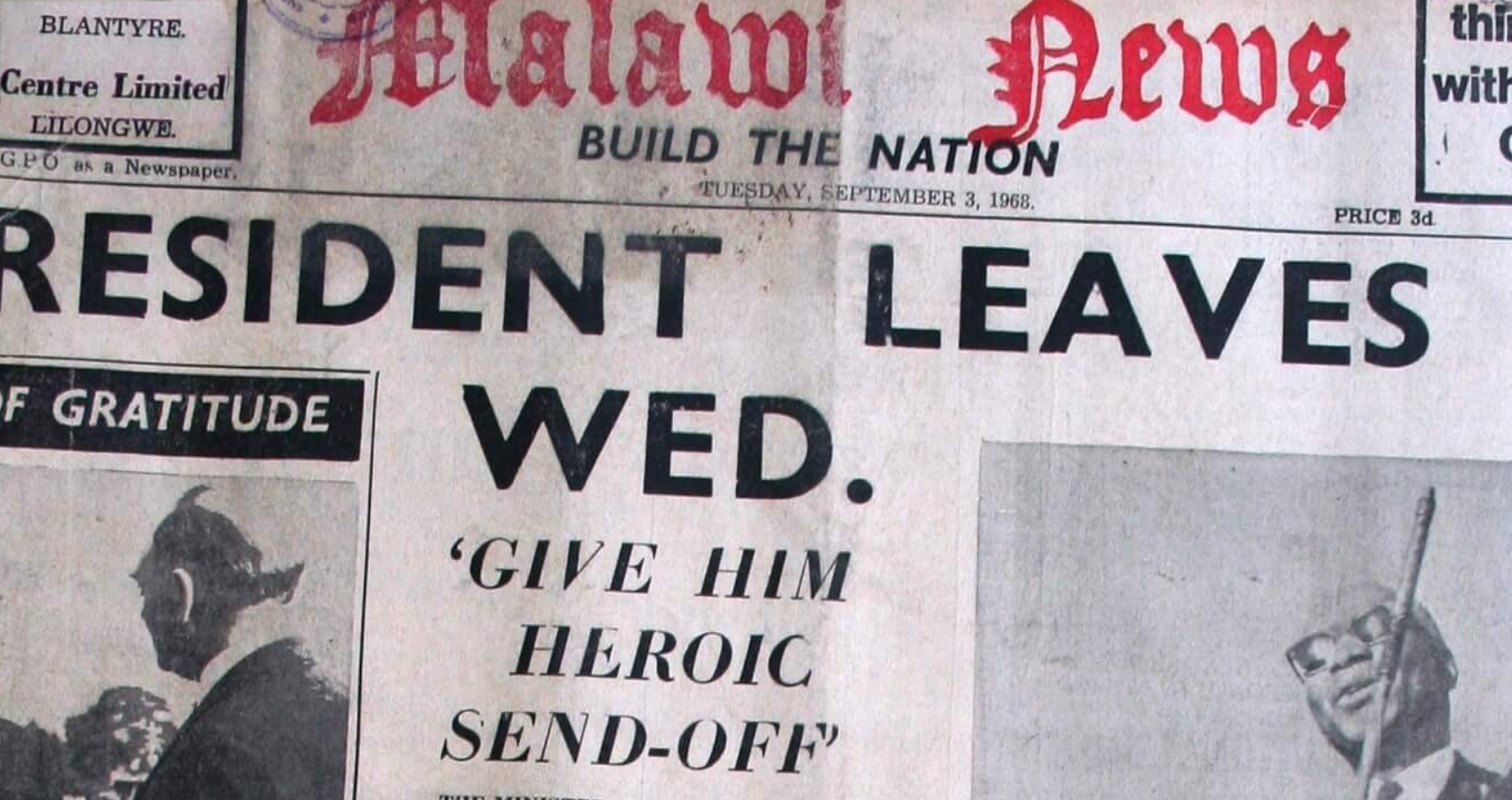

At home, he needed The Daily Times, which had a relatively high circulation of around 12,000, to cultivate his image—alongside his party’s paper, The Malawi News—as a wise and dynamic leader. He used an international service to beam state-controlled MBC to beam external broadcasts that countered mounting criticism from “rebels led by Kanyama Chiume, Willy Chokani, Yatuta Chisiza and other Dzigawenga” [his words] who had sought asylum in Tanzania and Zambia.

Local journalists were among the many arrested by the police in those days. One of them was our reporter, Peter Chirwa, who had joined the paper after working for the Catholic Church. Others were picked up from other media organisations like MBC. My own turn to be picked up inevitably came later; apparently, one or two cabinet ministers had become miffed at me for saying that I would only carry a photograph of Dr. Banda on the front page of the Daily if it made news, or if it related to an important story. Some even commented on the fact that I had failed to wear, on the lapel of my suit, the MCP’s badge of honour that bore the face of the Ngwazi.

BADGE OF HONOUR

This badge was a ubiquitous symbol of the MCP. Anyone who considered himself or herself a staunch and unquestioning supporter of the regime would never consider appearing in public without it. As far as the police were concerned, my failure to wear the badge was reason enough to pick me up for questioning and screening.

But my brushes with the political police were nothing compared to the crackdown that was launched soon afterwards against local journalists. In May 1973, the Special Branch raided our offices after a story was aired on the South African Broadcasting Corporation [SABC] that Malawi and Portuguese colonial forces had clashed on the Mozambique border after pursuing FRELIMO guerrillas into Malawi. The story was denied as a pack of lies by the authorities. It had been filed by a stringer, but the police swept in many reporters. Those of us who could prove that we had not filed the story were released after questioning. But others were not so lucky. Up to eight reporters, the cream of the Malawian press, were kept in detention for four and half years for their perceived role in that story.

Among them from The Daily Times were Levison Lifikilo, Austin Mmadi, who was our Crime Reporter, and Victor Ndovi, a young, bright all-rounder. Others who were arrested at The Malawi News were its former editor Mathews Ndovi, Sub-Editor Lloyd Piringu, and Douglas Chikwawa. Author and freelance journalist Edison Mpina, and Roy Manda who was a senior journalist at the Ministry of Information, were also arrested.

For those of us who survived, these kinds of pressures gradually took a toll. We became cautious and self-censored in our writing. Our general state of mental depression was gradually reflected in a Daily Times that lost its soul. The paper was simply filled up with lots of foreign stories, mostly about life in Uganda under the rule of Idi Amin, or about the Middle East conflict, and hardly anything of human interest here at home. A secret joke that did the rounds in the newsroom when we were short of inspiration and stories went like this: “What the good Lord shall fail to provide, will be made possible by Kamuzu and Idi Amin.”

Kamuzu and Amin both passed on. And so have most of the journalists that helped to steer The Daily Times through that turbulent epoch. Three decades down the line, those of us still around can only thank God that we survived that era. We marvel at how the paper survived and went on to make an important contribution to our young democracy. I was honoured to have been the founding editor of The Daily Times. I salute my brother editors and all the staffers, past and present, whose contributions made it possible for The Daily Times to become Malawi’s leading newspaper.

Alaudin Osman