“The source of ethics – family. The source of all great ambition – family. All renowned moralists say – respect the family.”

—Mendel Portugali, 1912

One morning a few months ago, I got a WhatsApp message from my friend Ben, who works as an editor at a publishing house.

“Yoni, I’m in the north. I’ve just left the Havat-Kinneret Museum and you won’t believe what I’ve found here,” he wrote.

A black-and-white photo popped up in the chat box. In the foreground, six armed young men—five of them sporting moustaches—posed before an old-style kibbutz building.

The round face of the man furthest to the left—staunch and chubby, toting a scimitar in addition to a raised pistol—was, in the clearest way possible, my own.

“Amazing, right?” wrote Ben, adding that he had seen the photo in a class he was taking to become a trail guide. “I immediately asked our instructor who this was but he had no idea. All he knows is that the picture was taken here somewhere around 1912, and that the guys in it are members of Hashomer. Is it your great-grandfather?”

My great-grandfather, Mendel Portugali, was the chief commander of Hashomer (“the Watchman”), the first Jewish paramilitary group in Ottoman Palestine. Founded in Jaffa in 1909, Hashomer combined a utopian socialist ideology of communal farming with aggressive Jewish nationalism. Its members guarded the lives and property of Jewish settlements in Palestine, and advocated for “Hebrew Labour”—the replacement of all Arab workers in Jewish villages with unemployed Jewish immigrants. Their uniforms were a strange blend of Bedouin and Cossack costumes, like an army outfitted by a gift shop in the Old Jaffa tourist center.

Hashomer was dismantled in 1920 and rebuilt as Haganah, the Yishuv’s military organization during the British Mandate. In 1948, the organization changed its name and structure one more time, to become the IDF.

Mendel was born in 1888 near Kishinev, Moldova. He was exiled to Siberia at age 15 for socialist activity, and returned home just in time for the antisemitic pogroms of 1905. Together with Israel Giladi, a classmate, Mendel organised the Jewish defence in their village, became a Zionist, and immigrated to Palestine, where he and Giladi co-founded Hashomer. In 1917, the story goes, Mendel dropped his gun and it went off, killing him.

When I received Ben’s message, all of my knowledge about my great-grandfather stemmed from the Israel-history textbook I’d read in high school and from a visit to a military museum during my army service. My father, the minor spy novelist Mendel Portugali, rarely spoke of his famous namesake.

In an unfinished autobiographical multi-generational magical-realism kibbutz novel my dad started writing before he died, the narrator complains that “the figure of his grandfather, leader of ‘Hashomer,’ chased his grandson like a shadow, creating around him unachievable expectations of a brilliant military career.” When the hero finally decides to become a novelist, he has to “flee the kibbutz his grandfather was buried in, and run into the great city of Tel Aviv. Only there could he escape the eternal burden of comparison, the disappointment of his parents and classmates.”

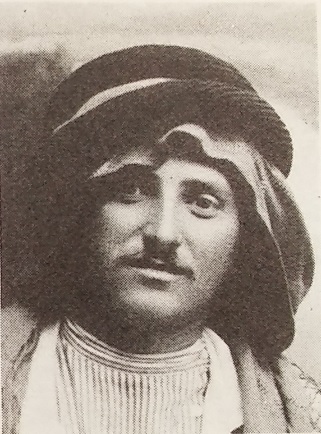

I compared the photo Ben sent with the profile picture from my great-grandfather’s Wikipedia page. Wikipedia-Mendel was pictured close-up, head wrapped in a kaffiyeh, wearing a striped button-down shirt without a collar.

His face was flatter and more symmetrical than mine, less doughy, his features speaking of both naïveté and responsibility. Ben’s Mendel, on the other hand, resembled me completely. Same eyebrows, same angles of the jaw, same nose. We even share the same awkward camera-shy pose: the same sideways glance, the same hand in the pocket.

I showed my wife Toony the two pictures for further examination.

“Pasted. It’s your face,” she said, zooming in on Ben-Mendel’s neck. “ A very professional job.”

Before studying art, she had gotten a degree in graphic design. “Isn’t it kind of similar to the dust jacket of that book you edited for Ben’s press?” she added.

Best Friends, a self-financed novel I edited two years ago, is about the friendship between a Canadian-Jewish businessman named Moni and his Hebrew-speaking dog. The jacket shows the head of the author—a Canadian-Jewish businessman named Moni—pasted onto the body of a labrador retriever.

I phoned Ben.

The photo was taken in the museum, he insisted. If we didn’t believe him, he added, we were more than welcome to come up to Havat Kinneret and take a look at the original.

Trying to avoid a two and a half hour bus ride, I sent the disputed photo to Gidon Giladi—founder and director of the Descendants of Hashomer Society, manager of the Hashomer Museum in Kfar Giladi Kibbutz, and grandson of Israel Giladi, Mendel’s former comrade.

I’d met Gidon once, a few years ago, on the tenth anniversary of my father’s death. In the Kfar Giladi dining hall, he told me that he and my father had been classmates. Then he took out his phone, and showed me a photo he’d taken of my dad right after he was stung in the face by a bee.

“Hi Yoni,” Gidon responded a few hours later. “Good to hear from you. The photo you sent me from Havat-Kinneret is wonderful, and indeed I know it very well. It’s easy to identify the Hashomer members in the photo, because additional photos were taken on the same day, in the same place, by the same photographer, and they are wearing the same clothes. To answer your question—your great-grandfather is not in the photo. The guy on the left who stirred your curiosity is Hashomer member Jacob Slachansky, also known as Jacob ‘Rascal.’ We don’t have a lot of information about him. Hope I helped, G.”

“Jacob Slachansky” gets you nothing on Google, nor does it appear in the index of Hashomer Anthology (1929) or Hashomer Book (1956), two collections of memoirs published by veterans and bequeathed to me by my father.

I did manage to find a single, brief mention of the man in a heavy tome entitled The Men of Hashomer in Their Life and Death (1991). I found the book in a dusty closet in my mom’s portable storage room.

Jacob’s surname, spelled slightly differently from the way Gidon wrote it, pointed me to a very short biography. “Slochansky, also known as Jacob ‘Rascal,’ was born in 1895 in a small town near Vilnius, Lithuania. When his father, a lumber merchant, died, Jacob immigrated to Palestine. He was immediately accepted into Hashomer, and served as a watchman in Havat-Kinneret. More details about his life are hard to discern. As far as is known, he later married a pioneer called Esther Bloch, and passed away on 31.5.64. He is buried in the Hashomer cemetery in Kfar Giladi.״

Next to his bio was a small headshot. When I showed the photo to my mom, she screamed. Then she asked me to remove the book from her premises immediately, and never bring it back.

I could understand my mom’s reaction, of course—no one wants to find out she gave birth to a person who basically existed already. But I was fascinated. Every time I looked at the two pictures of Jacob or showed them to someone (I showed them to everyone), I felt like I was looking into my own eyes. Was he funny? Why weren’t his memoirs published in the Hashomer books? Did he hate writing? Did he have grandchildren who remembered him? I had to know more.

Of the 20-odd books on the shelf dedicated to Hashomer in Tel Aviv’s public library, I found just one other mention of his name, in an autobiographical chapbook by a member named David Tzelvich. Slochansky is mentioned there in passing, as someone who joined the author and a third member in an infamous operation against Nissan Kanterevich, manager of the collective Sajara farm near Tiberias. One night, the trio surrounded the manager’s house and threatened him: if he did not fire all his Arab workers and hire Jews in their place, he would be killed. The incident aroused great anger in the Jewish settlements at the time, and today is considered one of the first Jewish terror attacks in Yishuv history.

That was it for Jacob Rascal. My great-grandfather’s name, however, was everywhere on that shelf. I was surprised to discover that even his letters had been published recently, by the Ministry of Defence.

I sat down on the floor and binge-read the letters. I found out that just like my father, who missed my birth because he wasn’t sure he wanted to oblige a child who might take away his writing time, Mendel missed the birth of his first son because of some minor quarrel in Merhavia (“something has happened and we need to go. Whoever is born, if I do not come, name him. Sorry”), and that like his great-grandson, who needed four months to finish the present essay, he too struggled with writing: “I am jealous of those who are able to write very, very much, about any topic. How happy I would be were I able to write, write, write, but my nature is to write little at a time when the heart feels much.” I also learned about an apparent shopping addiction: “I bought myself a horse. It’s awful. I did not intend to buy a horse. It was an act of the devil. I completely forgot I don’t have any money. Only one thing comforts me—the fact that I bought myself a horse.”

I decided to borrow the book and write a short essay about it. On the way to the lending desk, I stopped for a moment at the computer room to check if Slochansky’s name or that of his wife, Esther Bloch, appeared somewhere in the periodical collection. It was a longshot—the library’s digital periodicals’ catalogue began in the early 90’s, 30 years after Jacob’s death. To my surprise, however, two hits came back—a magazine article from April 1992 entitled “Murder in Ein Harod,” and another entitled “Graves Cry Out in Ein Harod,” from September 1991. I quickly scribbled the names of the two articles on a notecard and approached the periodicals hall.

The Tel Aviv Municipal Library periodicals hall is still the huge grey room I knew as a schoolboy. Its walls and columns are bare concrete, its tables are long and made out of old wood, the daylight that streams through its windows is perfect. I really love the elegance of its simple kibbutz-style architecture, and if I weren’t habitually uncomfortable in silent work spaces—I’m always worried my belly will make some strange noise and everyone will hear, this is basically all I think about when I’m in a library—I would have come to work here everyday.

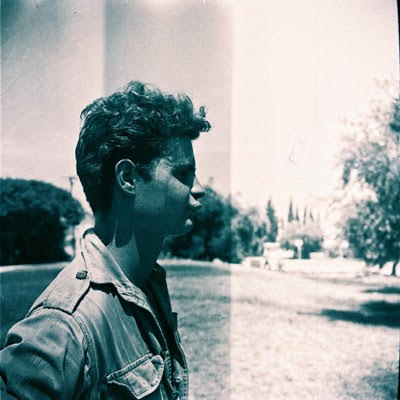

“‘Murder in Ein Harod’, April 1992… let’s see… ” called the librarian in a delicate, 30-years-of-reading-hall-whispering voice. He leafed through the 1992 volume, until his finger stopped on a blood-red headline. Under it lay Slochansky’s picture, in profile. His hair was combed to the side, like mine, and his face was a bit chubbier and younger than in the photo Ben had sent. He was photographed seated, wearing a festive, embroidered dress shirt, like he had been groomed for the occasion. The photo was dated Vilnius, 1905.

“The killer,” explained the caption below. “A charismatic, but very sick man.”

My first reaction was a small shrink in the stomach, like the one you get when you unexpectedly hear very bad news about family or close friends, only about 88% weaker. Then I noticed the librarian was reading the caption. Was he always curious about the stories he helped people find, or did he notice the resemblance, too? He was already working here when I first start visiting this library in high school, so he probably knew my face as well as I knew his—severe, clean-shaven and pink-toned, some grey hair is growing from the sides.

“It’s not me,” I said, and took the volume from his hands.

The hall was empty except for an elderly man napping on a leather sofa with the day’s newspaper spread over his legs. I sat at the nearest table and began reading. The first article, “Graves Cry Out in Ein Harod,” turned out to be a very short piece about the grave of one Aryeh Enderman.

Decades after his death in 1927—ostensibly from a shooting accident—his descendants found out that he had, in fact, been murdered. The gravestone had been replaced, mentioning the murder. “Enderman, a pharmacist in the Ein Harod hospital, had a love affair with a fellow kibbutz member, a married woman, who worked in the hospital as a nurse,” read the article. “The woman’s husband, a generously proportioned man known as Jacob Rascal, was hurt by his wife’s betrayal, and even more at being cuckolded by a namby-pamby doctor. One evening in October 1927, the husband arrived at the hospital and demanded that the pharmacist accompany him to the vacant field next to the cemetery. There, he shot and killed Enderman.”

The second piece, “Murder in Ein Harod,” came out a few months later, and seemed like a long sequel to the earlier article. It covered four pages, at the centre of which was an interview with Slochansky’s wife, Esther Bloch, an elderly woman in her late eighties, who “spoke for the first time after 65 years of silence, about the secret scandal of Ein Harod.”

“He was a talented and handsome man,” Esther told the interviewer about her ex-husband. “But he suffered from paranoia. He would see things that never existed—hallucinations. When I became pregnant, Jacob became extremely jealous, all of which led to the violent ending.”

On the last Thursday of October 1927, she told the interviewer, Jacob dragged her to the pharmacist’s hut, planning to confront the pair with his suspicions. His plans were spoiled by the fact that Enderman’s fiancée, Rivka Shmul, was spending the night in his room. The following night, Esther told the journalist, her husband paced nervously, walking in and out of the hut they shared. Then he suddenly disappeared. Esther, who was eight months pregnant, was lying in bed. When she heard shots outside, she panicked and dove under the covers. Jacob appeared in the doorway and fired three shots. The bullets landed in the exact place her head had just been. Then he raised the gun and shot himself.

Some friends from his time in Hashomer hurried to his rescue, and presented the incident to the British authorities as a shooting accident. Slochansky, who was only lightly injured, was sentenced to nine months in prison for killing Enderman. After his release, he was expelled from the kibbutz and forced to leave his family. His name was expunged from the histories written by his Hashomer comrades. He moved to Tel Aviv, became a taxi driver, and died alone in a housing project in Kiryat Shalom, about one and a half kilometres from the street I live on today.

Jacob Slochansky’s acts of violence and tragic end as an old, lonely man continued to occupy my thoughts throughout that week. The whole story struck me as a distorted version of one of my favourite books, Vladimir Nabokov’s Despair. The novel is narrated by Hermann Karlovich, a Berlin industrialist undergoing business difficulties, who encounters his exact double on a business trip to Prague. Hermann decides to murder his double, steal his identity, and then fraudulently claim a life insurance policy. In the book’s final pages Karlovich’s plan is uncovered easily by the authorities, because, we learn, the only person who saw any resemblance between the narrator and his double was the narrator himself.

When I re-read the book a couple of years ago, I thought that Karlovich’s scheme represented a yearning to change identities, to embark on potential life-paths not taken. Now, after experiencing a double-story of my own, I have begun to think of his actions in terms of loneliness. Seeing yourself in someone else requires an illusory intimacy, a belief that you really know the other person. It also requires someone who knows you well enough to acknowledge the resemblance. But both Hermann Karlovich and Jacob Slochansky were lonely men, men whom no one could—or even wanted to—identify with. Not even their closest friends and family.

I felt that I should try to find my double’s descendants and share with them the little information I’d found about their forgotten ancestor. I felt weirdly sure he would have done the same for me, if I’d been born first.

My only lead was the article’s mention of Jacob and Esther’s two daughters—Gila, who died in 1991 while hiking on Mount Carmel, and Tamara, “fair-skinned and as pretty as Gila, but in a different way,” who was born in 1927, a month after the murder. Tamara, it said, married a man named Eitan Lavie, and “was left with more questions about the murder than others in the family.”

I called Information and asked if I could check the last address at which Eitan and Tamara Lavie had been registered. With any luck, I thought, their children would have inherited the apartment or house. “I have an active phone number under these names in Haifa,” the operator replied. “Shall I connect you?”

Jacob Slochansky’s son-in-law picked up the phone after three rings.

I introduced myself—Yonatan, a writer from Tel Aviv, interested in speaking with Tamara.

“It’s Yonatan,” Eitan reported summarily, as if they’d been waiting for my call.

The receiver changed hands.

“Hi Yonatan,” said Slochansky‘s daughter. She had a deep sabra diction, clear and crisp, like that of a Feldenkrais instructor.

Yes, her father was named Jacob, she replied. And yes, he was a member of Hashomer, as far as she knew.

I couldn’t believe it. I felt like I was speaking to a character in a book I’d just read.

I was calling, I explained, following some research I’d done about her father. I’d found a few mentions of him in books about Hashomer, and wanted to hand them on to his family.

Tamara thanked me and asked why I had been researching him.

She laughed when I told her about the resemblance, but withdrew when I suggested meeting up. “You sound nice,” she said, “but I’m not interested in speaking about him to anyone.” She would be happy, however, to receive the photos and mentions I’d found. Before she hung up, she gave me her email address.

I sent her everything the same day.

Tamara answered my email six days later, thanking me for the material she received “yesterday.” (As our correspondence went on, I learned that she checks her email once a week, at a set day and time, as though she were visiting a postbox.) “Sadly,” she wrote, “my relationship with my father was very distant. Only in the last few years, as I’ve gotten older, I’ve started to regret it.” She was especially delighted to get his picture, she wrote at the end of her message. “I have no pictures of Jacob.”

I next wrote to Tamara a few weeks later, after receiving an unexpected missive from Gidon Giladi. He had stumbled over an anecdote about Jacob Rascal in the Hashomer Museum library. “A Hashomer member called Schneurson did guard duty with Jacob in Yavne’el,” Giladi wrote, “and made a bet with him over some trifle for a twelve-egg omelette. Schneurson won, but Jacob couldn’t afford twelve eggs. What could he do? He climbed onto one of the roofs and retrieved twelve pigeon eggs. Schneurson ate the omelette and spent a week in bed with stomach-ache. From then on,” Gidon concluded, “Schneurson avoided omelettes.”

“Sabbath greetings, dear Yonatan!” Tamara replied, emotional, six days later. Giladi’s omelette story, it turned out, had stirred a very personal memory for her, about her first encounter with Jacob, in 1941. “The main thing I remember from that meeting,” she wrote, “is the sudden nausea I felt during the meal. My father was so happy that we were meeting, and despite his simple house he tried hard and served a canned preserve from British army supplies—considered in those days a rare, expensive delicacy. I remember that I tried to taste it and got nauseous. Up to this day I am unable to eat store-bought canned fruit. Thanks and best wishes, Tamara Lavie.”

I sent a third and final e-mail to Tamara two weeks later, a sort of farewell, after the piece I’d written on the book of Mendel’s letters had appeared in Ha’aretz. I included a link to the article, and updated Tamara on two more facts connected to her father that I’d learned while rereading Mendel’s letters. First, I found a mention of the same terror attack described in David Tzelvich’s memoirs: “It is too early for these kind of actions,” Mendel wrote to Tova, my great-grandmother, about Jacob. “The fact that there are men who are able not to think about the interest of the workers, but just do whatever arises in their head—is terrible.”

The second discovery gave me chills. Most of the letters that Mendel wrote to Tova in 1912 were addressed to Havat-Kinneret—the same place where the photo Ben had sent me was taken, in the same year. “My grand-grandmother probably knew your father,” I wrote Tamara, not sharing with her my next speculation—that my resemblance to him might have been due to an affair between my great-grandmother and her father.

“Dear Yonatan,” Tamara responded four days later. “I received your article about your great-grandfather’s letters yesterday, and the story interested me very much, as well as the unstable mental state of those men. It is hard from the immense distance of time to understand what really happened to them, they who sacrificed their lives for us, and the violent day-to-day reality they lived in. Can we judge their actions by today’s standards? Clearly not. It made me pause for thought and perhaps consider a more forgiving attitude toward things that happened with my father at that time. I and Eitan, my husband, have reread our correspondence from the beginning, and decided that we would be interested in a meeting with you, in which we can open up our hearts to each other. Would it suit you to visit us in Haifa on the Monday after next, at 11:00 in the morning? Your friend, Tamara.”

Two weeks later, at 10:57 AM, I was standing in the slightly neglected outer courtyard of a modest, low-slung stone building—a kibbutz house dropped into a suburb of Haifa mansions. At the entrance stood two identical, unmarked brown wooden doors. I knocked gently on one, not sure if both led to the same house. Then I called Tamara, who answered, and said she was on her way out.

A moment later, a tall, slender women emerged from a side access path. Her white hair was braided into a high bun, her face elongated. She didn’t look like me at all.

“Wow, you really are similar,” she said.

Tamara invited me into the house, leading me to a hidden third door, identical to the two at the front. Before entering, I turned back and looked across the street. Toony, who’d accompanied me on the train from Tel Aviv because she had wanted to see Tamara’s face, stood on the sidewalk, looking into the courtyard. “Not similar at all,” she pantomimed, then mimicked going to get a cup of coffee.

Eitan waited at the end of a small shaded corridor, sitting on a couch, wearing green pajamas and white sport socks. His face was round, smooth and ruddy, like that of a very large baby.

“Welcome,” he said in a thundering bass, and rose slowly to greet me. On the table in front of him were two chessboards, all set up for a game.

“Just so you know, there’s no escaping Eitan without a chess match,” said Tamara.

“To be honest, I haven’t played in a long time,” I replied.

“It’s OK, I haven’t either,” Eitan lied, crushing my hand as he shook it.

It was the first time I had ever visited with nonagenarians. The living room walls were given over to a giant bookshelf, mainly containing books on history and Zionism. The free wall, where a TV should have hung, was covered in dozens of framed family pictures.

While Tamara laid out some food, I examined the pictures of grandchildren and great-grandchildren. None of them looked like me either. So, I thought, relieved: I’m not related to Jacob Rascal, the murderer. Standing before the photographs, I was surprised to realize how much this speculation had actually been bothering me, as if finding out Jacob was my grand-grandfather might reveal, at once, some crazy, dangerous potential I didn’t know I had been carrying in me all along.

“So how exactly did you find us, Yonatan?” asked Eitan, sitting down slowly.

“From the magazine articles,” I replied, turning back to face them. Both of them had been mentioned in the stories as people who continued to show interest and investigate what had happened in Ein Harod, I explained.

“Oh, you read that thing…” Eitan blurted out, looking at Tamara. We were quiet for a moment.

“Are you married?” Tamara asked suddenly, looking at my ring.

“Yes,” I said, “her name is Toony. She’s an artist.” I did not mention that she was currently, more or less, in their courtyard.

“On the phone you said that you wanted to write something about Jacob?” Eitan asked.

Well, I responded, when I realized that it wasn’t Mendel in the photo, I thought I’d try to write a short essay weaving together all the traces I’d uncovered about my double. Then that I’d discovered he had already been written about. The romantic triangle, the murder. Everything.

“It was a Dreyfus affair!” Eitan suddenly burst out. “That’s what you need to write about! We have suffered in silence for thirty years. Enough! It’s time to do justice!”

Between ’91 and ’92, when the articles about the affair and the murder were published, Eitan and Tamara were living in the U.S., where Eitan worked for a time. While they were away, they had missed the opportunity to make public a piece of evidence they had obtained, one which they believed proved decisively that there had never been a love affair between Esther and Enderman.

When he and Tamara had started going out, Eitan explained, his fingers knocking nervously on a green file he’d brought from one of the other rooms, all of his friends—and even his family—opposed the match. Everyone believed that Esther Bloch had had an affair with the pharmacist. Tamara was seen as the daughter of an adulteress and a thug.

“My mother was ostracised by the kibbutzniks for years,” Tamara interjected. “After the murder, they refused to accept her as a member, she always had to get by on her own.”

“I didn’t believe Esther either,” said Eitan. “But I wouldn’t give up on Tamara.”

For years, Esther refused to discuss the issue with her daughter, only increasing the suspicion. But one day, early in the eighties—half a century after the murder—they found out that the pharmacist’s fiancée, Rivka Shmul, was living in a small village in the Upper Galilee and was prepared to talk. “We immediately went to visit her,” said Eitan, “and wrote down everything she said about that night.”

Eitan pulled two thin, yellowing, photocopied pages from the file, covered in dense handwriting in blue pen. “I, Rivka S. of Amirim,” he began to read, “recalling here, by the request of Eitan Lavie and his wife Tamara Lavie, the events connected to the murder of the late pharmacist Mr. Enderman by the late Jacob Slochanski at the end of the year 1927, and this is what happened.”

Eitan looked up at me. “Now listen well.”

“I was the unofficial girlfriend of Mr Enderman,” he continued. “He was then around 32 and I was 24. We worked together in the hospital. We began to develop a physical relationship which went as far as kisses or hugs, but didn’t get any more intimate than that.”

Eitan interrupted the story, raising his finger. “She looked us in the eye just like you’re looking at me right now. I was the daughter of a rabbi,” he continued. “I got a religious education as a child, I had natural modesty and shame. One Friday, Jacob came into my room and demanded an answer to a shocking question: am I,” Eitan pointed to himself, “having sex with Mr Enderman or not? I was shocked by this outburst, and by the obnoxious question. I stammered the truth—no. My answer prompted another flare-up from Jacob, who said ‘then Enderman must clearly be sleeping with Esther! There’s no way he can live without a woman. I’ll kill him!’ And he left.”

“Do you understand what happened here?” asked Tamara, and for a moment I wasn’t sure anymore who was speaking—was it Tamara or was it Rivka Shmul? And who, exactly, were they trying to convince—me, or my dead double, her father, Jacob Rascal?

“I ran at once to Enderman’s room,” Eitan continued reading. “And I told him what had happened. He laughed! Enderman admitted to me that he liked Esther, that she was a good nurse, but that all this talk of relationship and intimacy is nonsense. I want and need to add here that for all the years since, I’ve been dogged by a certain sense of guilt. Had I said yes,” Eitan read slowly, taking turns looking at me and the page, “had I lied, it could all have been avoided. I hereby declare that Esther Bloch had not the slightest part in the events that led Jacob Rascal to kill Enderman. She had no intimate relationship with Enderman, neither spiritual nor physical,” concluded Eitan. “Only I did.”

He put the pages on the table and looked at me. “These things need to come to the attention of the public!” he declared. “The question is but one: have we convinced you that there was nothing there?”

I wanted to say that no one but them—and me, and Toony, I suppose—remembers those two articles today, and that even if someone did, a confession extracted fifty years after the events, from one of the parties, would not constitute proof. A betrayed fiancé, claiming her lover was true only to her? If this letter proved anything, and if this strange story I found myself inside of reinforced anything, it is only the central, surprising role imagination and fiction play not only in collective concepts like “nation,” but even in the most intimate and private ones like “family.”

I looked at Tamara, who gave me a sharp, narrow, look.

What if Jacob wasn’t being paranoid? What if she was the daughter of the pharmacist? Maybe that’s why she didn’t look like Jacob—and why she didn’t look like me.

She sat silent, her eyes concentrated on mine, waiting to hear my reply.

“Yes,” I said.

Note: Some names have been changed.

Translated from Hebrew by Josh Friedlander.