I am sort of obsessed with The California Photograph. You know the one I mean? It’s taken from above, of a valley in Yosemite blanketed with pine trees, bookended by sheer rockface. Or actually it’s of a particular curve of the Pacific Coast Highway, a thin strip suspended improbably over crashing waves. Or it’s of the hulking, undulating hills of the Marin Headlands at night, the rusty strip of the Golden Gate Bridge illuminated. It’s of the vast and endless Pacific, framed by cliffs.

There is not one California Photograph; it’s a whole genre. It’s one that’s nearly as old as modern photography. Indeed, the colonization and settlement of the American West and the birth of popular photography were intertwined—linked in ways that are hard to untangle. In the second half of the nineteenth century—beginning in 1848, to be exact—gold was discovered in Sutter’s Mill, California. This was shortly after the invention of the daguerreotype, the first widely available photographic process. Its popularity exploded in the 1850s; that same decade, more than a quarter million people traveled West to California. People went West because they saw it in photos, and people took photos because they went West.

The West had always been a myth to people back east, but it was more so when they hadn’t seen it. This is hard to appreciate today, when nearly the entire world is accessible to us in three dimensions on Google Maps. But back in say, 1861, when thirty mammoth-plate photos of Yosemite Valley by Carleton Watkins were sent home and shown in New York, it was a revelation. “As specimens of the photographic art they are unequalled,” The New York Times declared. Some of Watkins’ prints eventually made their way to President Lincoln; in 1864, after seeing them, he declared the valley untouchable, the first protected land in the country.

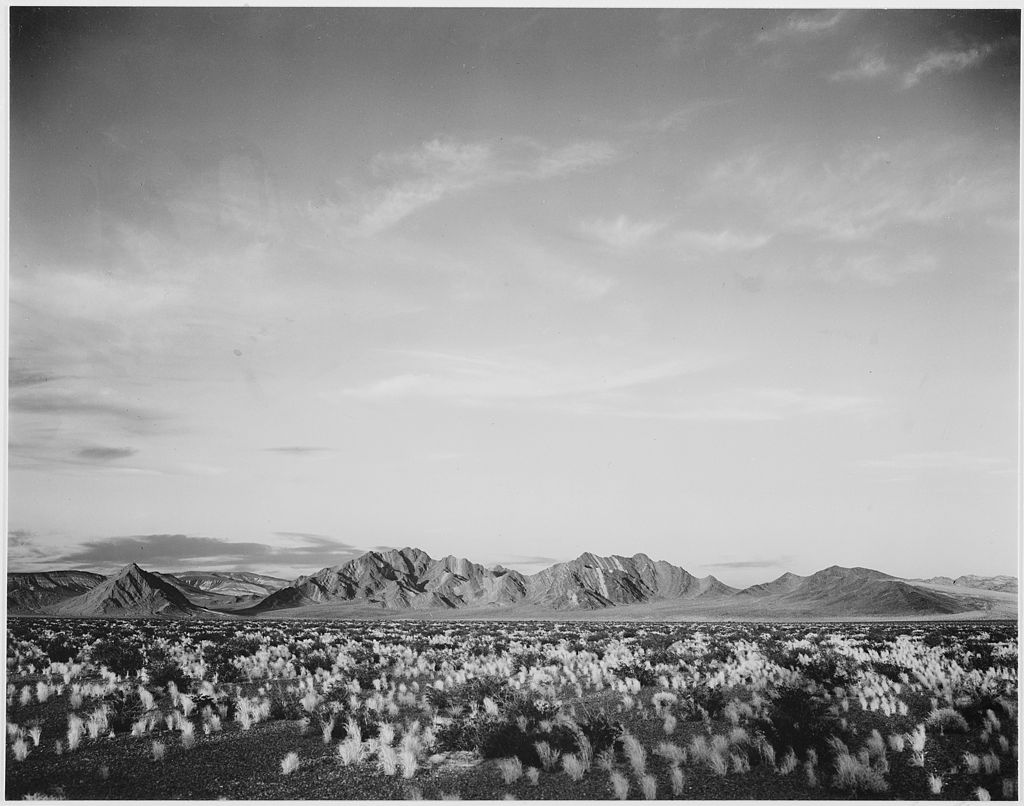

These California Photographs were almost always vistas rather than close-ups. A lot of this had to do with how huge and bulky early cameras were; you had to lug your equipment up to one spot and stay there for a long time. Watkins wrangled a dozen or so mules, carrying about two tons of equipment, up to high points in Yosemite where he could capture waterfalls and valleys and peaks. But this perspective is also due to—and helped create—a rhetorical, artistic view of the West and California: big, expansive, operatic, unpeopled and unspoiled.

This was always a myth, and not a benign one. It was a myth of erasure; the photos largely portrayed a land with no people and no history, a kind of blank slate of wilderness. This was not true—native people had lived in California for centuries, and had been driven out of Yosemite Valley in the early 1850s. These photos became bound up in a set of other myths, and created new ones, about the purity of land, ripe for the taking.

Ansel Adams is basically synonymous with the California Photograph. Adams was working later than Watkins and other early photographers such as Eadweard Muybridge, at a time when photography was more widespread and technically simpler. Beginning in the 1920s, and over his long career, he photographed all over the American West, sometimes on commission from the government. But like Watkins, he remains most famous for his photos of Yosemite.

People often refer to Adams’ work as “majestic” or “sublime,” both words that manage to capture the combination of beauty and sheer terror of nature. I know why people say that and I’ve felt it myself, looking at his work: this sharp cliff, that drop-off, the mountain solitude feeling. But I think what is most striking to me about his photos is their clarity: every pine needle is sharp. The combined clarity and enormity of his black-and-white prints is almost crushing.

Adams had the same politics as many conservationists of that era. He was an early member of the Sierra Club, and he hoped that by documenting the land he might help save it. (Sometimes he photographed people, but they were always a secondary interest). He was troubled by what he called the “resortism” of the National Parks Service, which after World War II, was eagerly encouraging more and more visitors to come to the parks. He vehemently protested the building of roads in Yosemite. He believed, rather obsessively, misguidedly, that his photos might convince people that the wilderness needed saving. He didn’t seem to connect the popularity of his photographs with the popularity of the parks.

Recently I have become interested in a different kind of California Photograph, which is a genre devoted to the landscape decimated and plundered and improved upon to the point of desecration. These are not hard to find; since the mid-20th century, photographers have been coming west to photograph the rundown boom towns and gas stations of the west, the urban sprawl and foreclosed McMansions and rusted out cars. The aerial view of highway after highway, endless city lights.

Photographer Mitch Epstein’s series “American Power,” taken in the early 2000s, captures some of this. He didn’t only photograph California; he photographed the landscape and networks of energy all over the United States. He called it a “response to the American dream gone haywire.” Many of the photos are large vistas: a lake and a canyon, obstructed by intricate infrastructure for a dam. The series, like many of Adams’ photos, lies somewhere between documentary and art (fake categories, but still a little useful). In particular I was struck by his photos of the region around Altamont Pass, in the San Joaquin Valley.

In one of these photos, men are playing golf in a green patch surrounded by desert. Dozens of wind turbines are whirring behind oblivious men in golf shorts, bent over their tees. Pale desert sky is empty above them. This photograph is on view now miles away, in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston as part of a show called “Ansel Adams In Our Time.” I looked at it for a long time, and then left, and then circled back: the artificial oasis of green, the spinning infrastructure of energy, the oblivious humans.

There’s a way in which Epstein’s photos are a sort of negative of photos by Adams or Carleton Watkins—the anti-postcard, a kind of record of time passed and what has happened to the place. But that’s not quite it. Epstein’s photographs are not ugly; they’re arresting. This is true of many of these contemporary photographs of California. It is strangely beautiful to see the alien eyes of a power station at night. It is eerie, in a wonderful, surprising way, to see a golf course emerge from the desert and marvel at what man can do—you could maybe even say that it is sublime.

It is always stupid to say that a place is “full of contradictions,” because, well, any place is. Playing on a place’s contradictions is one of the great devices of travel writing, a cheap trick. People do this a lot when writing about California. Joan Didion, great Chronicler of California, was extremely good at this trick, as Barbara Grizzutti Harrison pointed out in this very good and very brutal piece. Didion’s sentences often employ juxtaposition: floating camellias/madness, water hyacinth/shootings, roses and jasmine gardenias/Mercy Hospital—death with a side of flowers. Journalists and researchers and other people do this too, often less elegantly. So about California we have so many narratives fueled by dualities: rich/poor, urban/rural, desert/farmland, empty/full, beautiful/plundered.

For awhile, I was looking at these different genres of California Photograph—the Adams and the Epstein—through those lenses: before/after, old/new, pure/ruined, nature/man. That’s how I saw California too, and there’s of course a sense in which it’s true. Time has passed and things have changed and the land is on its way to being ruined, and if things had happened differently in the 20th century and the 21st that might not necessarily be the case.

But these dualities only get you so far. It’s still a kind of trick, a way of looking at two things at once, and seeing contrasts without really seeing the whole. California Photographs can be documentary but they are also windows into particular myths. Looking at them side by side doesn’t necessarily dispel those myths. If anything, seeing a photo of an abandoned power plant next to a photo of Yosemite Valley makes the state seem all the more bewitching. There’s a sort of beautiful pull to disaster, a sense that the state is subsumed in a beautiful, terrible way. This is perhaps strange extension of our idea of the sublime.

This kind of beauty also exists in photos that are taken of wildfires, a kind of California Photograph that becomes more common every year. I am thinking especially of a viral image of palm trees against a hell-colored sky taken by Los Angeles Times photographer Marcus Yam, a perverse inversion of the classic California fantasia of a sunset behind the palms. Photos like this might awaken some horror in us, some latent understanding about what man has done to nature, if we can draw the connection clearly in our minds between us and the burning state. But they also awaken a kind of awe.

This is not usually true of the photos of the aftermath of wildfires; perhaps these evoke most clearly what man has done to California.