“A ball may fall, but it can also come back up, by rebounding, for instance. Heat cannot. This is the only basic law of physic that distinguishes the past from the future…The link between time and heat is therefore fundamental: every time a difference is manifested between the past and the future, heat is involved.”

—Carlo Rovelli, The Order of Time

I burned my hand quite badly the other day, in the brief fleeting instant when the handle-ness of the handle of the deep pan we’d been using to roast an enormous piece of meat somehow cognitively cancelled out the other piece of relevant information—to wit: that the entire pan had been in the oven (not atop the stove-top) so that the handle had reached the searing, optimum temperature of 425 degrees, minus a couple degrees for momentary cooling. In that split second, I made a crucial and fateful decision: I reached out and gripped the handle. Since the handle had become part of the cooking, my hand briefly did too.

It was extremely painful, wouldn’t recommend. I put my hand under cold water—and after some quick googling revealed that cool is better than cold, we warmed it a bit—and I found myself thinking, as I cooled my hand in water, about how a piece of meat keeps cooking even after you take it out of the oven. In any case, the pain was so numbed by the water that the dominant note of the experience was only dread, as I waited for the full particulars of the situation to reveal itself. How badly was I burnt? How much of my hand had become meat?

Cooking is all about time, and in that strange thoughtless instant, a minute portion of the careful, calculated application of the tremendous heat that we were using to turn a large piece of raw cow flesh into a delicious meal was transferred onto the palm of my hand; it was the tiniest flicker, the most minute sliver of a second, but it had changed everything, a little bit: instead of eating the meal we had cooked, we would spent the rest of the evening on hold with our insurance’s teladoc and Lili’s mother, and I would spend days after that with my world constrained by the wound, defined by the parameters of its limitations.

More than that, I found myself disoriented, and found it hard to concentrate. Pain does that: time slows down, or moves in a rush, and you’re like a swimmer caught in the waves. At one point, I was on the phone with the teladoc and Lili was on the phone with an advice nurse, and she asked me a very simple question—what the password to log into my computer was, a question I answer every day when I log into my computer—and I had no idea what the answer was.

(A password? For my computer? I have a computer?)

The teladoc suggested that dressing and antibacterial cream were called for in the short term—which Lili went off to procure—and a doctor’s visit the next day; based on photos we sent, he predicted that the burns would blister and pus, but four ibuprofen would manage the pain; I could take acetaminophen as well, if needed, as that was “a totally different drug.” (I did not, as it turned out; about an hour later, the pain quite magically diminished.)

I’m not sure why we called Lili’s mother, other than to expand our circle of expertise; her father is a retired doctor, so we often consult him about things like this, but he was out of the country. And it’s always good to call moms (call your Mom, I bet she would love to hear from you.) But in markedly different mode than a doctor’s standard “series of questions followed by carefully-hedged recommendation,” she immediately recommended we apply “chuño” to the wound, a potato starch paste.

It was this, and it was simple: potato starch and warm water in a bowl, a thick consistency, wet and flowing, but heavy enough that when you poured it over the burns it would sit, and set; as it became a paste, stuck to the wounds, it would both cool and heal.

It is very strange to (briefly) turn your hand into meat, in part because of how it turns the banal experience of cooking a bit of meat into a moment in time. What would it would be like to accidentally cut off a finger, and see it become meat, there, on the cutting board? I’ve found myself thinking this, wondering this, as I cut slices of the steak we ended up having quite successfully prepared; the irrevocability of an accident makes it so very real, and for a moment—before I was borne back into the current of time deeply enough not to notice it passing—it felt like any kind of accident could do the same as the burn had, could push me out of the flow and make time stop.

The sheer chemistry of the experience is disorienting. And while I don’t welcome these thoughts—like standing on a high ledge and contemplating, against your will, what it would be like to leap off—I don’t try to repress them, either. Our bodies are meat. And time is heat, is entropy, is story: cooking is daily, cyclical, submersive, and amnesiac, but accidents are things you remember, that your body remembers.

Chuño, it turns out, comes from an Andean process by which potatoes are “naturally” freeze-dried. It may well have been humanity’s first invention of what non-indigenous scientists would later re-invent and name “lyophilization,” a chemical process by which moisture is frozen and then sublimated into vapor—rather than melted into liquid—thus removing water from a food (or other substance) without altering its physical structure. Ice will vaporize, instead of melting, in very particular conditions—and in industrial science, lyophilization is usually done by producing a vacuum—but one particular condition in which it will happen is the dry, low-pressure high-altitude areas inhabited by the indigenous people of the Andes, which allowed an open-air version of the process.

It’s simple and brilliant: potatoes are frozen during the cold winter nights and then, during the warmer days, at altitudes higher than 3,800 meters (below a certain humidity), the ice in the potatoes will simply turn into water vapor and float away, leaving desiccated, uncooked potatoes behind. There is more to it—stomping the potatoes allows them to become even drier and there is a process to making both “white” and “black” chuño—but the underlying process–freezing without electricity and drying without fire–is lyophilizing without industrial science.

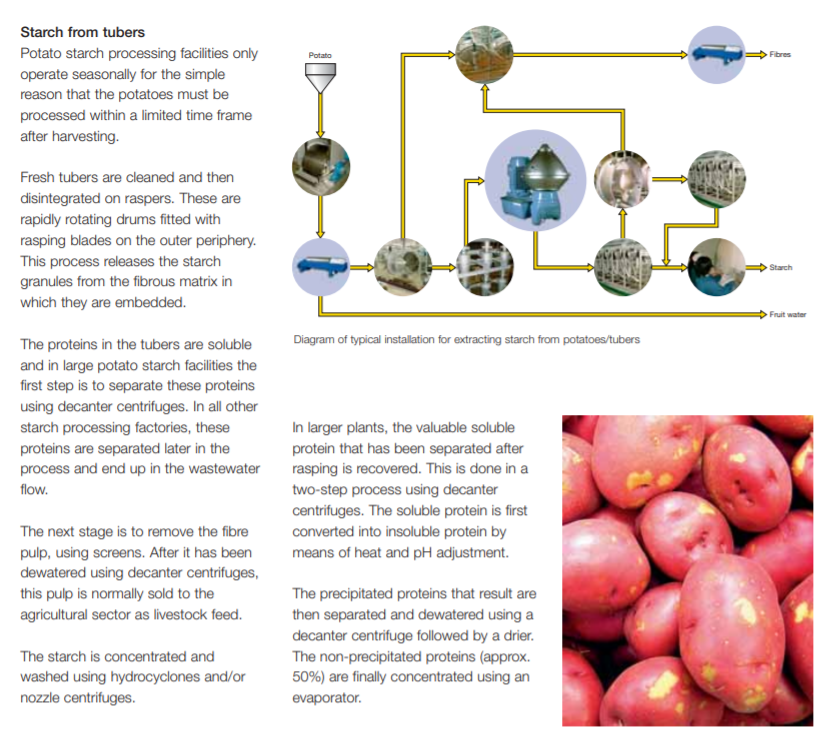

The potato starch we bought at the store, of course, is produced in a very different way, using electricity and fire and industry instead of the very particular climatic conditions of the Andean mountains:

But it’s all potatoes. Something about potatoes can survive being frozen and dried and unfrozen and re-hydrated; something about potatoes can be eaten this way, and something about potatoes can be applied to a burn, to make it feel better, and help it heal.

I wonder. We also wrapped a dressing on the wound: first smearing antibacterial cream on the burns, then folding a non-stick foam pad over the affected area, and then binding it with gauze. It was almost certainly overkill, and I took it off the next day—when the wounds didn’t blister—but it calmed me a great deal, to have the wound creamed, covered, folded away, and bound. It was like throwing a blanket over an angry parrot’s cage.

I called my mother-in-law yesterday, to tell her that my hand is much better; she tells me that chuño is a remarkable curative agent. She recalls her brother having hot water thrown on his face, and the chuño helping; she recalls using it on her children for a variety of burns and ailments; she has no sense for why it would work, for why something so simple could aid in healing, but she has seen it work many times, she says, and she knows what she has seen.

My hand is fine now, well enough that I can use it to type, and to do most things; the raised ridges that threatened to become blisters did not become blisters, mostly, and though I can reconstruct exactly how the curl of my hand exposed certain parts of my palm to the burning hot pan-handle—and how other parts were spared—the superficiality of the burns are the only evidence that they existed. If I could not see my hand, I might not know that it was burned.

But it’s the strangest thing: I’m glad it happened, now that the pain is over and the story is all that’s left. I learned about chuño; I learned about burns; I watched my hand heal, amazingly fast. I had a nice conversation with my mother-in-law, after which we discussed her old chairs, newly placed out in the living room. The leather of the old chairs was very dry, having been sitting out for so long, so she’d been applying mayonnaise. Doesn’t that stink? we asked, shocked; No! she explained. It absorbs, like lotion into skin.

Aaron Bady