1.

Guns N’ Roses is still huge. Their “Not in This Lifetime” tour, which kicked off with a small show at Hollywood’s Troubadour in April 2016, and wrapped up its 2017 portion at the Forum in Inglewood, California, in November 2017, grossed over $500 million.

They got $104 of mine, for the November 21 show at Oakland’s Oracle Arena. On the three-hour ride between Nevada City and the concert, I heard their hit “Paradise City” on 96.9 The Eagle, Sacramento’s classic rock station.

“Paradise City” might be my favorite song of all time. It starts off with a single, graceful open chord, ten seconds of gentle strumming, then about five seconds of drums, then the chorus, which goes like this: “Take me down to the Paradise City where the grass is green and the girls are pretty / oh won’t you please take me home” and is repeated 14 times before the song’s end, six minutes later. (Those are full repetitions only.) The last minute of the song is basically a tease—will the entire chorus be repeated again? And finally it is. Axl sticks the ending, holding the word “home,” which somehow turns into the word “yeah,” and then, throwing out a last, perfect pitch, a deadpan sexy utterance of the word “Ba-by.” When I was a kid in the 1980s, I had a friend whose mom was a heavy smoker and whose discipline philosophy centered around screaming herself hoarse. Axl’s voice is like a sexy version of her voice.

If you are between the ages of 30 and 60 and you are white, and you can’t sing the chorus from this song, you are—I guess?—a conceptual artist? Or maybe you are a homeschooled Christian. But no. That’s a shallow read of you, and the song. If you can’t sing the chorus from this song I would be curious to know why, and I am sure it’s an interesting story.

I myself enjoy films in black and white, and ballet, and long, complicated sentences full of big words, emotions, and/or ideas. But if whatever music you’re listening to doesn’t make you want to dance or cry or fuck or bench more than you did last week, well, I guess I’m not quite sure why you’re listening to it, unless of course you’re listening to Brian Eno’s Music for Airports.

2.

I love music but I have always been timid around music people. I want their information but at the same time I know they feel they earned it while I was doing other things, like listening to the Bee Gees, Rosanne Cash, and Robyn over and over, or watching Prime Suspect again.

Sometimes I wish I had an hour a day to ask tolerant music nerds about music but “tolerant music nerd” is a contradiction in terms. At the Oracle, which holds 20,000 people, 15,000 of whom had better seats than we did, I sat between two of them: my old friend Adam, and his friend Gary. Gary and Adam are in an ’80s cover band called Wizard Van that just so happens to be my favorite band. I warned Gary when I sat down that I would be asking him a lot of stupid questions throughout the show and he assured me that was fine, because we were going to be here for the rest of our lives. He produced a set list for this tour, which he had gotten off the internet, and which apparently had not yet been deviated from in any major way, or any way at all, to prove this.

There were 33 songs on it—33 songs for a band with 1.2 good albums. “Jesus Christ,” I said. “Is this a set list or is this L. Ron Hubbard’s Mission Earth?”

Gary agreed that the set list was comically long. “This is where I’ve scheduled beer number two.” Gary pointed to the song “Better,” which I had never heard of. “This is where I’m peeing and possibly getting beer number three.” He pointed to “Wichita Lineman,” which, for the young folks reading this, is an extremely famous country song by Glen Campbell (and for you feminists out there, FYI, Campbell’s crazy ex-girlfriend, Tanya Tucker, is so much better than he was).

Gary continued. “This is where I make my exit.” He pointed to the last song before the encore songs, of which there were five—and of which “Paradise City” was last.

I didn’t know what was more upsetting to me—that Axl Rose was going to sing “Wichita Lineman” or that Gary was going to leave before “Paradise City.” “ ‘Paradise City’ is one of the greatest rock songs ever written,” I said. “I just heard it on the way down here, in Auburn, on a stretch between Target and the exit onto 80.”

Gary said that I should probably retain this as my memory of “Paradise City.”

“Does Guns N’ Roses really suck in concert?”

Gary looked at me funny. “You didn’t know that?”

“Well I saw them in 1994, at the Coliseum, but I mean, that was, a long time ago. Anyway, if they suck, why are we here?”

“I have no idea,” Gary said. “Anyway. Is ‘Paradise City’ your favorite?”

“It’s my third favorite,” I said. I then listed for him my wholly unsurprising Guns N’ Roses top five, most of them from their first and most popular album, the 1987 Appetite for Destruction: “My Michelle,” “November Rain,” “Paradise City,” “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door,” and “Mr. Brownstone.”

“Wow,” Gary said. “No shame,” he added. Which of course meant, shame. I guessed that his favorite was “My Michelle,” but it was “Rocket Queen,” the last song on Appetite. Such a music nerd choice, and a good song, but “Rocket Queen” is still—just, please. There’s a reason you’ve heard of the other songs but not “Rocket Queen.”

(A year later, I have to confess: Gary was right about “Rocket Queen.” It sounded like dogshit in concert, but the recording of it, which I never paid enough attention to, is fucking awesome.)

3.

Aside from my not wholly paranoid but perhaps outsize fears of terrorism and fires, I enjoy being in a huge concert arena waiting for a show to start. I am relaxed by the outer-space vibe of the vast, lit-up darkness, and warmed by the camaraderie as fellow lovers of this fine band arrive with friends and loved ones.

At around 7:20, I got in the bathroom line. The concert was supposed to start at 7:30, but I figured they’d be late. They weren’t. At 7:40, I was still in line and the opening chords of “It’s So Easy” thudded through the arena. Throngs of people started running past those of us who had made this poorly timed decision. Some abandoned the line and sprinted off, but not me. I could live without hearing this song.

The girl in front of me in line was around 21 and wearing a shitload of eye makeup. She fit in well in this overall heavy-eyeliner crowd. I did spot the occasional tech nerd, but other than that the crowd was not terribly “cool” or “young” San Francisco. In fact, if forced to describe the median attendant of this concert, I would say it was a 45-year-old woman with dyed blonde hair from Concord wearing a lattice-front top, acid-washed jeans, and a lot of black eyeliner and foundation. The girl in front of me might have been the daughter of such a person.

We waited and waited. The girl turned to me and said, “I’ll be fast. I’m always fast.”

“I’m fast too,” I said.

“Yup,” the girl said. “I’m fast unless I’m pooping.”

4.

A typical Guns N’ Roses song starts with a sort of slow, even dreamy beginning, maybe with lightly shimmering or restrained percussion. Then, generally, comes the riff, insistent, menacing. Strong as the riff starts out, it quickly doubles in size—it has to, to match the nasal cruelty of Rose’s voice and the power of the drums. When I was 20 or 21, some Guns N’ Roses’ songs—“My Michelle” and “Mr. Brownstone” in particular—felt as scary to me as horror movies do. I couldn’t listen to them alone, and if I did, my hair would stand on end and I’d start checking closets and stuff.

In the recorded version of “Mr. Brownstone,” different guitar sounds zigzag all over the place. It brings to mind a black ballpoint pen furiously scribbling out a drawing of a buxom woman sitting astride a drooling wolf before the teacher sees. In concert, “Mr. Brownstone” brings to mind an armful of plastic-covered library books tumbling down a flight of stairs.

During the next couple songs—weird songs I have literally never heard of, like “Double Talkin’ Jive”—I didn’t really listen at all but tried to work out why even the good songs sucked. Obviously Axl’s voice was not what it once was, but better enunciation would help a lot. Slash by himself sounded good. But the thing that makes Guns N’ Roses really good are those guitars and Duff McKagan’s Precision Bass® all chasing each chasing the other this way and that. On this particular evening, they were just sort of bumping into each other a lot, like, “Oh, you again?”

They played “Chinese Democracy” and “Welcome to the Jungle.”

Adam said, “I feel like I’m watching KISS.”

I know who KISS is. Still, I didn’t know what he meant. I asked him later and, like a true music nerd, he pretended not to hear me.

5.

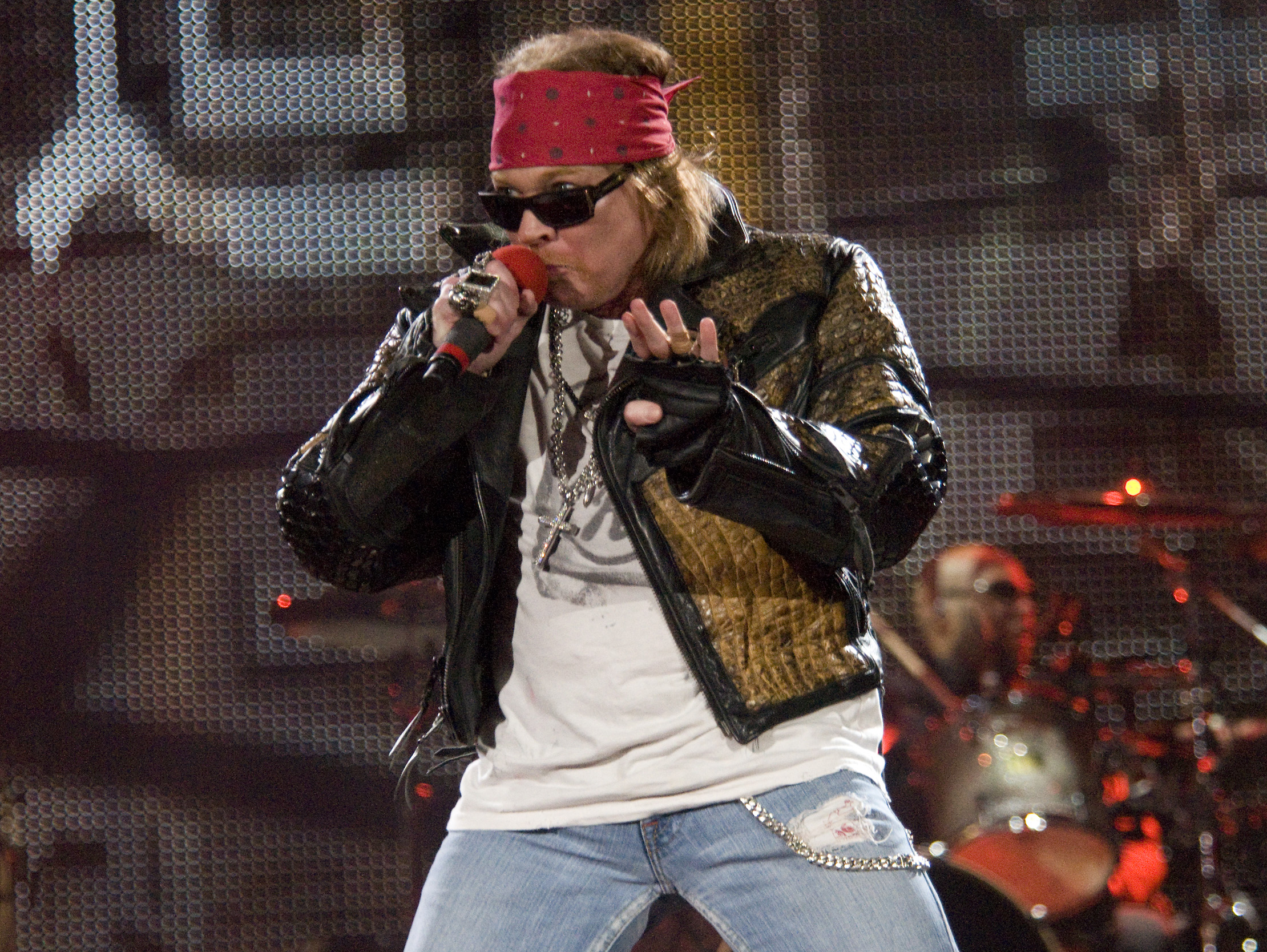

We were pretty far back: section 212, row 10 million. In the authentic arena-rock tradition, my concert experience was mediated by the screens. Much of my enjoyment of the show came from staring at Axl, trying to get a sense of his face. I had seen photos of his not-very-well-considered plastic surgery, and now, seeing him on video, I wondered: When he went to the plastic surgeon and was asked, “What are your goals?” was Axl like, “fuck if i know,” or did he have an idea of how to restore his youthful beauty, which had been considerable, and it went FUBAR? It probably would have been nice if his doctor had told him that feline sleekness of his face had an expiration date that could not be extended with the use of preservatives.

I think it is particularly hard for people who were at one point gorgeous to accept aging. Those of us who are merely good or average looking, or ugly, we don’t know what it’s like to lose a face like that, and it might be less painful to have some funhouse version of it than just a generic old one. When I saw Axl play next door, at the Coliseum, I was 24 and he was 31. I still remember the way he moved, the trademark elastic shimmy of his body, which used to be snake-like. It is now, I’m sorry to say, more squirrel-like. There are of course no injections for this, so Axl made up for the loss of erotic flexibility by running around a lot. He ran to the left side of the stage. He ran to the right. He ran backwards. He threw the mic into a corner of the stage, then, retriever like, retrieved it.

Someone threw a white scarf or T-shirt onstage and he waved it over his head. He set it down, and a few songs later, he picked it up and waved it again. I had forgotten Axl was from the Midwest—Indiana—but there is a gee-willikers midwesternism in his gestures. For example, when signing the titular line from the song “I Used to Love Her,” he turned a hand up hopefully toward the heavens, like, “Hey, I am a good guy, this all started out innocently enough!” Then, signing the song’s next line, “But I had to kill her,” he turned his hand upside down to indicate, “Hey, you know, there’s a limit to my goodwill, especially with the ladies.”

True to his word, Gary headed to the bathroom during “Wichita Lineman.” It’s a pretty repetitive song, and Axl has the opportunity to sing the line “The Wichita Lineman is still on the line,” several times. Every time, he presented this as if it were simply good news, with a sort of easy, palms-up shrug, as if he were telling us all, “You see? He’s still on the line! Nothing to worry about, all you nice folks who like linemen to be where they belong, i.e., on lines.”

At one point someone threw a plaid shirt up onstage and he tried to tie it around his waist and sing at the same time but I think the shirt was kind of small and he didn’t have a lot to work with, and it was both cute and sad. It became less cute when, announcing the members of the band, he introduced all the male members by talking about how they shredded or whatever and when he got to the sole female member of the band, he said, simply, “This is Melissa, she hates me.”

6.

The highlight of the show was that our friend Jeremy and his wife were sitting a few seats away from us, and Jeremy stood for every song and danced and air guitared a bit, and Adam kept taking videos of Jeremy and sending them to him with messages like “You look really good,” “Awesome 2 see u rocking out so hard,” and “Someone tried to tell me you were not that cool and I punched them they are dead now you’re welcome.”

The second-best part of the show was this dude sitting in front of us, a guy around 35 who had retained the stink of the frat. Every time there was an iconic song or moment, like Slash’s solo during “November Rain,” or the chorus of “Civil War,” he stood, turned around, raised his beer, and shook his head incredulously at those of us who had not bothered to stand. It was a performance he’d clearly perfected, in a long life marked by disappointing showings from people he wished would party harder and just be more stoked.

7.

November Rain was song 24. (I should mention this article was written prior to Joshua Clover’s excellent article for Popula on the “November Rain” solo.)

“This is a terrible song, except for the solo,” Gary said, citing a popular opinion.

I wagged my finger at Gary the way women who grew up with insane dads think Bernie Sanders wagged his finger at Hillary Clinton. “You are incorrect,” I said.

I acknowledged that the main part of the verses is treacly and kind of tuneless:

When I look into your eyes

I can see a love restrained

But darlin’ when I hold you

Don’t you know I feel the same

But as he heads toward the chorus, Rose’s adenoidal desperation brings the song to life:

If we could take the time

To lay it on the line

I could rest my head

Just knowin’ you were mine

All mine.

Then it gets awful again, except for the solo. Fully 65 percent of this song is awful. But the 35 percent of it that’s not awful is really good, and I don’t know if those parts would be so good without the awful parts. “November Rain” is a song Guns N’ Roses created to express what Guns N’ Roses is.

8.

One stares at Axl in perplexed wonder and awe. One stares at Slash with only awe, followed by, because of the hat and sunglasses, a giggle. Yes, at 55, Slash still wears a hat and sunglasses onstage, and possibly when bathing. That said, when he plays he looks like he thinks he’s the only person on earth and the hat and sunglasses are what support this mythology. Plus, there is something extremely ridiculous about Gun N’ Roses. They have a great song whose main lyrics are “Well well well. You just can’t tell. Well well well, my Michelle.” Slash has to wear that dumb hat, and the sunglasses, because if the dumbness were not constant, each dumb part might be too dumb.

I read on Wikipedia that Slash first become obsessed with music when he went over to a girl’s house to “get in her pants,” but when the girl put on Aerosmith’s Rocks, Slash forgot all about her and just listened to the music. I don’t know where Slash lives right now but I bet it’s in some giant house in the Valley, and whenever I think of this concert I will think of him standing out by his pool, in headphones, listening to Rocks, wearing a tracksuit and his hat.

His hands covered the entire screen, and were adorned with so many rings they looked like Gaudí chapels. His hands are creatures all to themselves and they have created so many sounds that have shaped so many moments of our lives. If I had not learned—again from Wikipedia—that Slash wanted the chorus of “Paradise City” to be “Take me down to the Paradise City / where the girls are fat and they’ve got big titties,” I might actually want to ask him how he feels about all of it, but I think it’s enough to just listen.

9.

I mentioned I saw Guns N’ Roses at the Coliseum in 1994, in a bygone era. The plan was to watch them from the floor. We were standing there, drunk, stoned, waiting for the show to begin—Metallica opened—but the moment the first notes rang out, thousands of rangy white boys rushed the stage. We were three preppy college kids and we ran in the other direction. During our escape, we found $400 on the ground, and we bought a bag of weed and beer and sat way up top, watching everything from afar. My relief at being away from the stage and the swirl around it was actually intoxicating. That’s the moment I knew I was a chickenshit dork 4 life.

The first line of “My Michelle” is “Your daddy works in porno now that mommy’s not around.” They used to seem so terrifying to me. Whoever was being addressed here (Michelle?) seemed to have no future. These days, the idea that this song might be viewed by Michelle as some kind of rebuke, that anyone could get to her with that stuff, seems laughably archaic. If her dad works in porno, well, she probably lives somewhere where no one even cares, where maybe everyone else’s dad works in porno too, and where working in porno is totally fine—the important thing is that Michelle’s daddy has a job and may even lives in a big house with a swimming pool. This changed partly because we have been freed from this kind of repressive thinking, but mostly because Michelle now shares her shameful lack of a future with everyone.

Guns N’ Roses promised that something dangerous was clawing at the edges of your life and about to get you. They were right, but they were wrong about their idea that the clawing thing was vice. Bad life choices, doing drugs, fucking too many people, being a whore—it’s all just circus stuff now. The sun, the acid in the ocean, the rain that doesn’t stop, it doesn’t give a shit how much coke you do or how many people you fuck.

As Gary left I told him I figured out why we we were here.

“Oh yeah?” he said. “Why?”

“To bear witness,” I said.