I mostly never drink beer and mostly haven’t for over a decade. Sometimes I’ll drink a vodka tonic or a glass of wine or a cocktail or whatever it is that is being made socially… well, not imperative, but the path of least resistance, the “um, yeah, sure, I’ll have one” of whatever the social occasion might be. It’s not that it’s hard to say no, per se, but when it’s harder than saying yes, I’ll say yes (mere moments after deciding I’m not going to drink tonight). This fact—that in the moment I will say yes to a drink that, on reflection, I have already decided to say no to, and will wish I had said no to later—feels like one of those revelatory snapshots of who I am, as a person, that I can know about myself but lack the ability to change. When you turn forty, as I will on Saturday, it’s good to know a few things about yourself that you’re not going to be able to change.

I mostly never drink alcohol because it makes me sleep poorly, something that, as I’ve gotten older, has come to be of paramount concern. I like the taste and I enjoy intoxication in the way that most people do (I partied with the best of them in college, he says, forty-years-oldishly), but I started getting really nasty insomnia in graduate school at the same time I coincidentally also acquired a lot of temperance and pleasure-denying discipline; having always been an early riser, graduate school turned that into the basic rhythm of life. I started getting up at four or five, every day, and starting work immediately, with coffee; I still have pleasant memories of waking up and walking the precisely 0.4 of a mile from the mother-in-law apartment I lived in, then, to the café where I would sit in a window-seat and watch the sky lighten.

It’s 6:37 as I write these words; I haven’t been able to sleep past seven in well over a decade, and I’ve been up since five. Not because I’ve been drinking, but just because. But if I’ve had a beer, or two, the chances are good that I’ll stay up later than usual and then, when I get up at 4:30, which I will, I will be extremely groggy; as the day goes on, I will become increasingly petulant and short-fused, and really cannot be around loved ones who will put up with it, or it will get worse and worse. I will need to find some excuse to go outside—a long walk with the dogs or some shopping errand—and something about being around strangers will force me to emulate a human being who lives in a society. I have learned about myself that if I am with loved ones who will put up with my silliness, I will be silly.

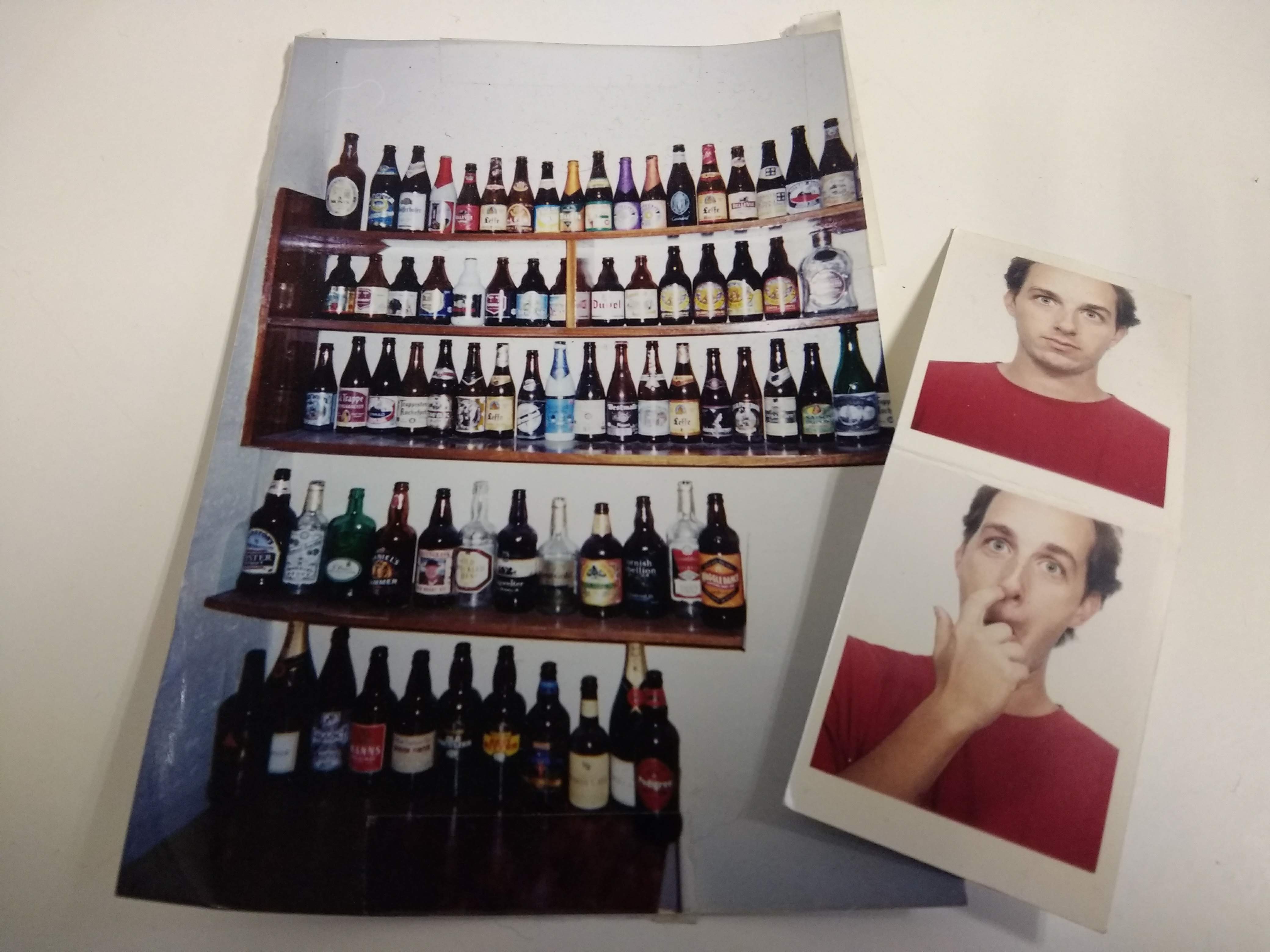

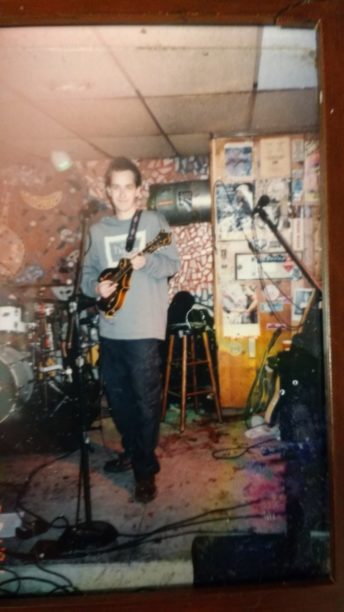

Before I went to graduate school, I drank beer. I used to brew it, in fact. When I was a seventeen-year-old soon-to-be ex-Appalachian, the guitar and banjo players in my dad’s band (I played mandolin) taught me how to brew beer from malted whole grains and for my birthday, my parents gave me a nice set of boiling pots. It was not a problem that I was not nearly close enough to legally purchase alcohol; if you brew your own beer, you will not run afoul of the law against purchasing alcohol. One of my brewing uncles lived on a farm without running water or electricity in Lincoln County; the other had a PhD in philosophy. One of the songs I played with both of them was “Whiskey Before Breakfast.”

A propos of nothing: the county I grew up in was dry. To buy alcohol, you had to drive over the river into West Virginia, where the “Last Stop” was also your first stop, unless you wanted to continue on to Krogers. It never seemed like any of these restrictions hindered anyone’s ability to get very drunk as needed.

To brew beer, you don’t need to do very much beyond use good ingredients and keep things very clean. If you want to hit a precise flavor profile—match a particular style or create a particular new one—you have to worry about a lot of things; you have to get temperatures just right, measure amounts precisely, time everything just so, and if you want to learn a little chemistry, it will not go unrewarded. But the underlying process, as one of my brewing mentors told me, was simple enough that it could be done by people on every corner of the planet using some of the most basic implements and cookery. You need starches which you’ll use heat to turn into sugars and you’ll need yeast to turn those sugars into alcohol; if you keep everything clean—so that other bacteria can’t get to the sugar before the yeast does—then what will come out the other end of the process will be excellent beer.

Anything else is a desire for control: you can make precisely the beer you want—and re-create it later—by controlling all the factors that go into it.

I decided that I didn’t want much control. Does one drink beer for control? I was seventeen. I wanted each beer I brewed to be a surprise, or as I preferred to think of it, a discovery, and one that was impossible to replicate. Less an achievement than an event, and less an experience than a memory.

In my greatest innovation, I decided to see if it were possible to brew beer over a wood stove in my backyard. It was: the trick was to build a small wood fire, let it burn all afternoon to build a nice bed of coals, and then use a leaf blower as a bellows, to stoke the fire when you needed it to be hotter. It was not precise. It was smokey and dirty and it took a long time; my nice clean pots that I had always used on our kitchen stove got extremely sooty—permanently—and all the equipment would be filthy by the end of the 8-10 hour process. But it could be done.

Here is how to do it: grind the malted grain—roughly ten lbs—and after bringing the water to a boil, let it cool it down to about 170F, so that when you add the malted grains, you can keep the water at 150F or just a hair hotter; after letting it mash for an hour or so, start draining the wort—the sugary not-yet-beer—while adding more hot water to the top, so as to gently strain all the sugars out of the mash; after collecting all the wort, bring it to a rolling boil, add hops in the last five minutes of the boil, and then remove it from the flame. Place it in the bathtub, filled with ice, to cool it down as quickly as possible; you want to minimize the time in which the wort is hot before you’ve pitched the yeast, but you can’t pitch the yeast until it’s cooled below 80F. Pitch the yeast, seal, and wait.

I suspect I will never brew beer this way again; it’s a memory because the factors that made it come about are no longer available. My father doesn’t live in the woods anymore, and I don’t live in West Virginia; I don’t have brewing pots and kettles—not a huge expense, but a necessary one—and I’m no longer 17, no longer living in a dry county playing music with my parents’ friends. I mostly never drink beer. But I still sometimes play the mandolin, and “Whiskey Before Breakfast” is still the first tune that falls under my fingers. (Lord preserve us and protect us…we’ve been drinking whisky ‘fore breakfast).

Aaron Bady