On the 17th of February 1944 in the Austrian village of Gaaden, then part of the Ostmark of the Third German Reich, a young priest was making the rounds of the parish. He was Pater Cornelius Steffek, O.Cist., a monk of the nearby Cistercian Abbey Stift Heiligenkreuz. (Cistercian monks in Austria often serve as parish priests). When Pater Cornelius finished his rounds and returned to the rectory of Gaaden, he was met by the housekeeper who said “there are two gentlemen waiting for you in the parish office.” The “gentlemen” turned out to be a pair of Gestapo agents. They searched the rectory, and found numerous letters that Pater Cornelius had written to young soldiers in the Wehrmacht. They were letters of spiritual counsel, and they contained many veiled criticisms of the Nazi regime.

Some years before, Pater Cornelius had founded a Catholic boy scout group. After the Anschluss in 1938 the group was disbanded, like all non-Nazi youth organizations. But Pater Cornelius continued to meet weekly with his former boy scouts for an informal Bible study. He stayed in touch with them over the next few years as they grew older and were conscripted into the army. “Under the pressure of neopagan opposition,” he would later write, “their faith was strengthened.” And he tried to encourage them in their spiritual journey through the letters that he wrote them.

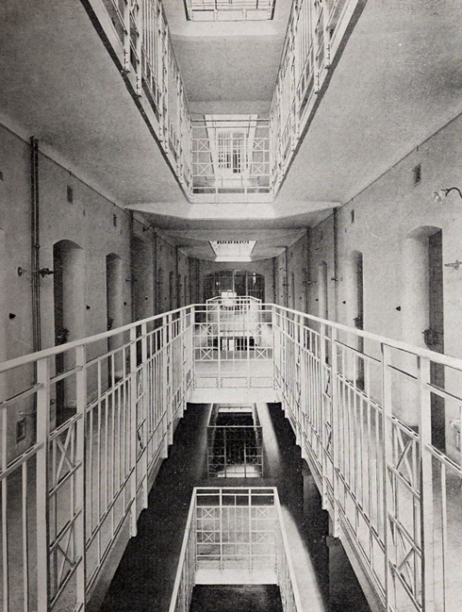

Pater Cornelius’s arrest on February 17th was part of a coordinated Gestapo operation against a number of priests in the greater Vienna area suspected of supporting illegal youth groups. According to the Gestapo’s report, they were arrested “on suspicion of conspiracy to commit high treason.” Pater Cornelius in particular was said to be “urgently suspected of being a threat to the security of the Volk and the state, because of his treasonous support for a bündisch -confessional youth organization.” After a long interrogation at the Gestapo headquarters in Vienna, he was brought to the Rossauer Lände Jail— the infamous Liesel— which was full of political prisoners. He was supposedly awaiting trial, but his trial never came.

He spent five months in the Liesel in a single cell. Another priest was in the cell next to him, and removing a screw in the wall they were able to talk to each other and pray. Every evening he gave his blessing through the window to the cell on the other side, in which he was told a nun was imprisoned. He would later recount that the food was so bad that he didn’t eat anything for the first few days, but that after that hunger proved itself to be the best sauce. After the attempted assassination of Hitler in July, 1944, he was moved to the Landesgericht Prison, where by autumn they were cramming seven prisoners into each cell. He stayed in this prison till April 1945, when the Russians were about to march into Vienna. There was a plan to move the prisoners out into the countryside, but events moved too quickly, and eventually they were simply released. A few days later Pater Cornelius was able to return to his parish.

When I entered Stift Heiligenkreuz in 2006, Pater Cornelius was already 98 years old, the oldest monk in the monastary, but still in better shape than many of his juniors. I was impressed by his remarkably good posture, and by the old world courtesy with which he addressed his confrères. He had been born in 1908 in Niepołomice, which is now in Poland, but was then in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. His father was an officer in the Imperial and Royal Galician Uhlans. To the end of his life, Pater Cornelius remained an ardent monarchist. The year after I entered Heiligenkreuz, Otto von Habsburg, eldest son of the last emperor of Austria visited us, and Pater Cornelius was moved to tears.

He was not entirely free of the childishness of old age. His younger sister used to visit occasionally and he would play cards with her in the guest wing of the monastery. The card-game usually ended in a quarrel, complete with accusastions of cheating.

Pater Cornelius died in 2008 at the age of 99, with the monks gathered around his bed praying. His death was one of the most moving experiences of my life. We could tell that he really saw his death as a passing over into the next life. At the time I had not yet made final vows in the monastery. Pater Cornelius’s death helped me to decide that this kind of life and death was what I wanted for myself. Later, after I was ordained a priest myself, I was stationed in one of the parishes in which Pater Cornelius had been pastor in the 1950s. The older parishioners often talked about him. Especially the old ladies. They talked about how much they had admired him. “Such a pious priest, and such a fine man. So polite, and so handsome!” He had taught them catechism class in school. “He was very strict, but in a good way.” I’m afraid they found me a rather disappointing specimen of priesthood in comparison.