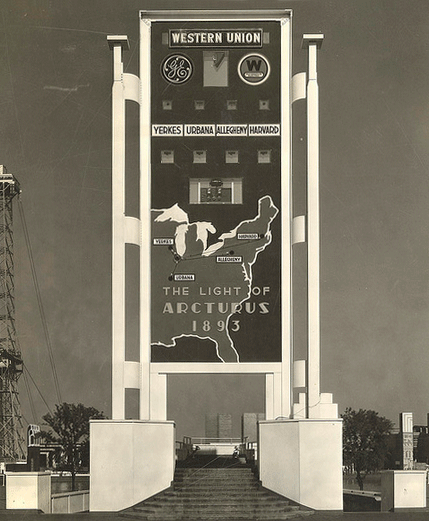

1933. Chicago was hosting the World’s Fair, heralding the Century of Progress while still in the throes of the Great Depression. Since the opening night, the eyes of the fair had been trained towards the heavens, turning its lights on when the rays of the celestial newcomer Arcturus had reached them.

Only new light would do for this new dawn, and predictably, the fascist governments of the world wanted their piece of it. The Graf Zeppelin had already made a showing on the behalf of Germany that October, commemorated by the U.S. Postal Service with a memorial stamp; when fascist Italy flew in for a visit, she made sure to leave us with a Roman column she’d stolen for the occasion.

Library of Congress

Library of CongressFinding said column was my brother’s idea: he’s the kind of person who keeps you up to date on the latest developments in the Spanish Civil War, and maintains a particular fascination with the cultural detritus discharged by the collision of fascism with the demands of polite history. That Christmas, he’d gathered my family in the living room so we could learn about that war by way of a fifty-two part animated series commissioned by the Canary Islands, in which a knock-off Berenstain Bear is conveniently present for every single major event up to and during the war, including spying on (what my brother has taken to calling) El Almuerzo del Golpe, the infamous forest picnic in which Francisco Franco and his senior brass decided how they were going to Do The Whole Thing.

From that perspective, it was inevitable that he’d take us there. It was the bottle of wine that you buy solely so you’ll have one in hand when you arrive at the party, a housewarming present given to you by actual fucking fascists that you still can’t manage to throw away, perhaps out of some sense that it might still contribute to a preferable history, but predominantly because that would be rude.

There was steel and sputter here, once. Twenty-five fascist angels, bearing fascists and a pilfered marble column, flying in on the last stage of a world tour to sing their songs of tradition and rebirth.

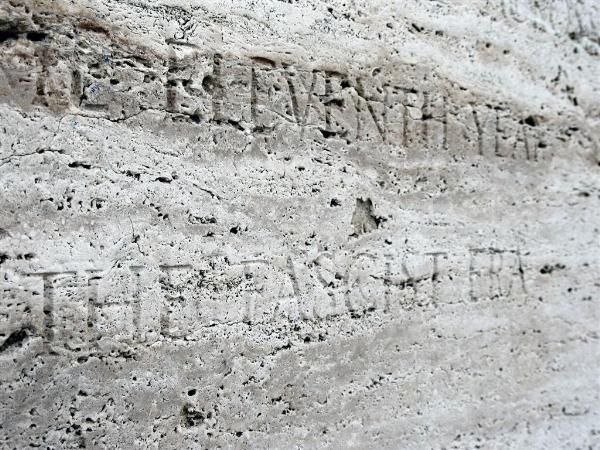

A stolen Roman column could be considered “hidden”, what with having been lodged next to Soldier Field and a memorial to dead cops, but it’s hard to get any other impression. The site is unlit, surrounded by dead trees, and from the path that trails next to it, it’s an arbitrary hunk of rock. It had an inscription, once, but time has made good progress healing over it; with a cell phone’s torch, one can barely make out the letters.

THIS COLUMN

TWENTY CENTURIES OLD

ERECTED ON THE SHORES OF OSTIA

PORT OF IMPERIAL ROME

TO SAFEGUARD THE FORTUNES AND VICTORIES

OF THE ROMAN TRIREMES

FASCIST ITALY BY COMMAND OF BENITO MUSSOLINI

PRESENTS TO CHICAGO

EXALTATION SYMBOL MEMORIAL

OF THE ATLANTIC SQUADRON LED BY BALBO

THAT WITH ROMAN DARING FLEW ACROSS THE OCEAN

IN THE ELEVENTH YEAR

OF THE FASCIST ERA

I stood there, in front of this dead thing, wondering what do with myself; I felt complicit in something that I couldn’t name. I checked over my shoulders, twice, and saw nothing; I asked my partner idly whether or not we should even be here. I was taken by the asinine – if not entirely incredible – notion that this place was somehow being guarded by the last vestiges of this certain kind of fascism, made esoteric by its Americanization, but the grass wasn’t flattened, let alone in any pattern approaching rows, and the only boot prints I could make out were ours. If it was worshiped, it was worshiped from a distance standing back on the path, on the way to places far more worthy of spending one’s time.

I wondered if this was a victory, but then I wondered whose it could have been. Anti-fascists – the kind you capitalize – wanted the statue taken down, and those who were more broadly against fascism at least wanted it to be moved, reshaped, somehow recontextualized. Neither got what they wanted. The statue exists; the fascists exist; they hold power we do not, use it in ways we would not, how could we have won?

Eco was right: it would be difficult for me to find the specific historical formation enshrined before me anywhere else, but within minutes I could leave this place and find the cults of tradition, the fear of difference, the promise of the common privilege of nationalism and the perverse need to be humiliated by a self-constructed enemy, and to extract revenge for that humiliation. Just because I found something unrecognizable doesn’t mean we’re at a comfortable distance, or that it’s left. “Take away imperialism from fascism and you still have Franco and Salazar. Take away colonialism and you still have the Balkan fascism of the Ustashes. Add to the Italian fascism a radical anti-capitalism (which never much fascinated Mussolini) and you have Ezra Pound.”

So what do we call ours? Call it white supremacy; call it the ideology of the Wall; call it America; you can see it if you haven’t already felt it. But I stood there, did nothing, and nothing happened.

I expected something ancient; what I found was something forgotten. I expected something evil, and that I suppose it is, but I expected a profane, dusty sort of evil, the type of evil that lodges bits of stone in your lungs if you inhale in front of it too quickly, but to describe it like that would be inappropriate flattery – the statue, at this point, is dead. It’s not a victory, but it could be a scene from one. Not everything can be destroyed, after all, and not everything is worth the time. Imagine less a world without the statue, and more a world where it may as well not exist.

In 1940, Italo Balbo was blown apart over Libya by his own anti-aircraft guns, but that death is immaterial to America’s Balbo. Ours may live again, resurrected in fascist resurgence. But for now, Balbo is dead.