It wasn’t that my grandfather Ben lacked the energy, his friend Dianne told me at her kitchen table in Houston, one spring morning last year. He was 75, but she’d seen him gardening like a man half his age, swapping out his entire lawn: shirtless, tearing up all that unsuspecting Houston zoysia just days after he’d arrived next door from out east, to replace it with imported east coast St. Augustine. And she’d seen him drinking and sparring over the news of the day with her husband into the wee hours. She knew he’d have the stamina. That wasn’t the problem.

“I don’t guess there ever was a safe time for a Jew to visit Saudi,” she said, “but it seemed this was the worst time.”

As head of expatriate services for ExxonMobil’s Al-Jubail Project, a joint venture with the Saudi government established in 1980, my grandfather’s wife, Joanne, had made a number of trips to the kingdom for work. She’d so far left her retired writer-producer husband behind.

In 1985 Ben decided he’d go. Joanne was 32 years his junior, a woman of 43 in the prime of her career. She was also nearly six feet tall, while he was no more than a few fingers above five feet. He was also a Jew; an atheist, but a Jew nonetheless.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, while Ben was working primarily for NBC, Saudi Arabia had seen intense development, increased secularization, and greater openness to the West. This changed abruptly in 1979, when religiously motivated critics of the monarchy targeted the Grand Mosque in Mecca. Although the attack was carried out by a small party of zealots, whose firing of guns in the mosque appalled most Muslims, their demand for less extravagance on the part of the Saudi rulers and for a halt to the cultural inundation of the kingdom by the West nevertheless struck a chord across Saudi Arabia. Religious conservatism was on the rise.

By the 1980s a visible uptick in anti-Semitic literature and the deepened authority of its sponsors in the Arab world began to suggest that anti-Semitism had become an entrenched part of Arab intellectual life.

Nevertheless, the United States remained in close cooperation with the Saudi government, and under King Fahd, the kingdom purchased even more, and more sophisticated, military equipment from the US. America and Saudi Arabia also stepped up their decades-old collaboration on oil. When President Trump talks about the alliance these days, we have to remember that this relationship began in 1931, with American geologist Karl Twitchell’s recommendations and, shortly thereafter, a massive infusion of labor and money from the Arabian American Oil Company (Aramco), which led to the first oil boom in the early 1950s. Aramco was behind much Saudi development in the decades that followed.

Public Domain

Public DomainWhen the oil embargo of 1973 and then the mosque attack of 1979 threatened to derail US-Saudi collaboration on oil, it was up to the people behind projects like Al-Jubail to restore and strengthen the relationship.

Ben wasn’t unaware of the risk. Shortly before they were scheduled to leave Houston he knocked on Dianne’s back door. “O.K., I want you to tell me the absolute truth about something,” he blurted. “I want your promise you’ll be completely and bluntly honest, O.K…. Do I look Jewish?”

She took a breath. “Do I look Gentile?”

“My God,” he said, shaking his head, “is it THAT bad?”

So she armed him with a Christian hymn. “I want you to memorize every word and promise me if you get arrested, you’ll start singing it,” she said. “It goes like this: ‘Whaaaaat a Friend We Have in Jeeeeesus/ aaaaall our sins and griefs to beeeeear!/ Whaaaat a pri-vi-lege to caaaaarry/ eeeeeverything to God in praaaaayer!’”

I have a letter that Ben wrote to my mother shortly before the trip to Saudi. They’d been more or less estranged for decades, but when Ben had cheated on his wife, my mother’s mother Hannah, the gulf grew. Apart from a couple of visits so he could attend her wedding or, later, see me and my brother, their only regular communication was a letter or two each year. My mother shared five of them with me.

In the one he wrote her before his trip to Saudi, Ben told her that Exxon would “play godfather” for him, and added that he was really obligated to go. “The Saudi Arab government wouldn’t give Joanne a visa unless she was accompanied by her husband,” he wrote. Why she needed her husband as a chaperone this time and not on previous visits to Saudi, I don’t know.

But this particular husband was also a Jewish-American journalist who’d spent a good chunk of his career producing radio and television programs exposing anti-Semitism and advocating Jewish causes worldwide. Starting, as far as I can tell, with his work for The Jewish Veteran in 1944, he’d scripted and produced and broadcast stories for the Federation of Jewish Philanthropists and the Jewish Theological Seminary (1946), the American Jewish Committee (Passover Drama 1948, labor discrimination critique 1949), and the American Jewish Council (“Free and Equal,” 1949). More recently it had been NBC’s “Frontiers of Faith” (“The Guilty One,” 1961).

They flew to King Khalid International Airport and made their way to Al Jubail on the coast. While in the kingdom, Ben mostly stuck close to Joanne, her Exxon colleagues, and a driver. Like many expats, he drank scotch or homemade wine every night, indoors and under the radar. Outdoors he took photographs.

One day he was snapping shots of what he believed were nothing more than sand dunes when Saudi police collared him. What interest did he have in military installations? They wanted to know.

You’d think a man who’d seen his own father killed in a pogrom by anti-Semitic state agents would have learned caution, particularly in a nation whose ruling class was at the moment hot with anti-Semitism.

In one of two albums of memorabilia I inherited after Ben’s death some ten years after his Saudi trip, I found two color drawings he’d made after returning home—grotesque scenes, exaggerations or outright fictions, I’ve always assumed, of his encounter with the authorities. They’re ridiculous Orientalist caricatures, and somehow also chilling. In one a female figure meant to be Joanne is on her knees before an angered, cartoonishly villainous Saudi man pulling film from a camera. She’s entreating him, with raised arms and wrists shackled, “But your honor, we don’t do it quite like that in Houston.”

In the other cartoon a shirtless and bony Ben kneels on the ground with manacled hands behind his back chained to manacled ankles, his head on the stump of a tree, neck exposed. He’s a caricature with an inhumanly narrow head and a giant nose, a wayward soul in the allegorical-stereotypical Beleaguered Jewish Body, but he’s also clearly my grandfather.

The Saudi man from the first sketch grips Ben by the hair with one hand while in the other he wields aloft a golden scimitar.

“Before you chop my head off,” the cartoon Ben is saying in a cartoon bubble, “don’t you think we ought to shake hands first?”

The Wall Street Journal published reports from anonymous sources that the journalist Jamal Khashoggi was tortured in front of Mohammad al-Otaibi, Saudi Arabia’s Consul General, before he was killed.

According to Reuters, which cited a Turkish intelligence source, Saud al-Qahtani, the top aide for the crown prince of Saudi Arabia had made a call to the consulate while Khashoggi was held there against his will. Via Skype Qahtani reportedly insulted Khashoggi, who responded in kind. According to the Turkish source, Qahtani then asked Otaibi and his team to kill the prisoner, saying, “Bring me the head of the dog.” According to several sources, the president of Turkey is in possession of the audio of that Skype call.

Khashoggi was still alive, sources have alleged, when Otaibi and his colleagues, while listening to music, cut his body into pieces. “There was no attempt to interrogate him,” one source said. “They had come to kill him.”

“It could very well be that the Crown Prince had knowledge of this tragic event,” Trump said in a statement the other day, “maybe he did and maybe he didn’t!”

According to Nazif Karaman of the Turkish pro-government newspaper The Daily Sabah, an audio recording with sound taken from inside the consulate revealed Khashoggi’s last words. “I’m suffocating…Take this bag off my head, I’m claustrophobic.” More recently various sources reported his last words were “I can’t breathe.”

Examining Ben’s artwork again, I wonder how hyperbolic his sketches are. How much they amplify the danger he was in. How much they’re played for laughs. Whether they conceal, in their corny cartoonishness, real anxiety he felt in the moment, or past trauma that the experience dredged up, whether from his childhood in war-torn Latvia or from the accident that took his mother’s life, or the pogrom that took his father’s.

Before you chop my head off, don’t you think we ought to shake hands first?

Ben tried explaining what he thought he’d been capturing on film—sand dunes, not some military base—while Joanne and his driver, “in all their wisdom,” managed to switch the active film with a new roll.

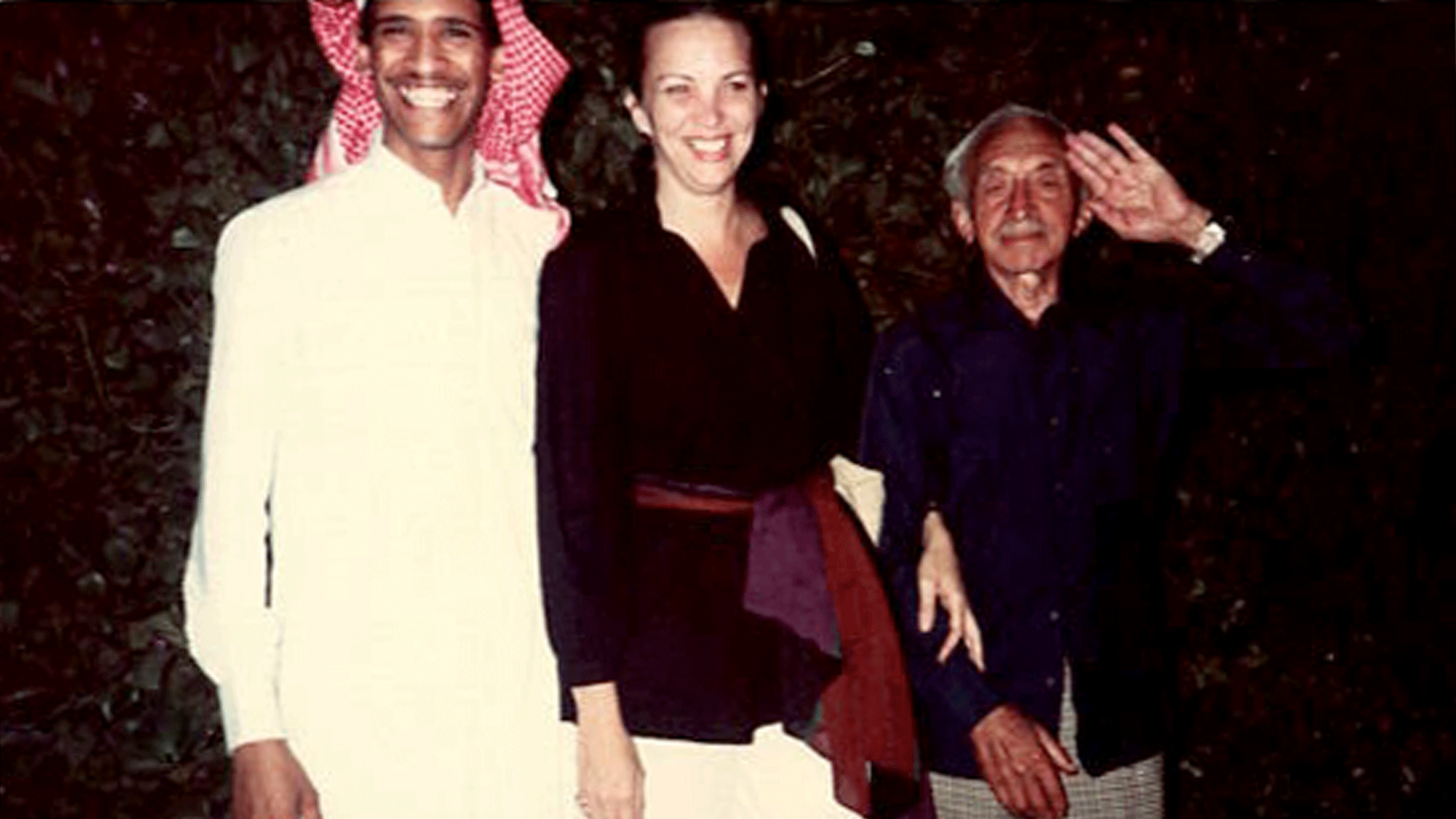

In a photograph from the trip, Ben stands in a pair of brown and blue checked slacks and a midnight-blue collared shirt with the bottom button undone. Next to him is Joanne, a full head taller, and next to her a young man with a huge smile wearing traditional Saudi garb: white long-sleeve, ankle-length thawb, red-and-white-checked headdress. Ben has cocked his huge left hand at his temple in a strange, palm-forward salute whose meaning I can only guess. I wonder if the photo isn’t somehow satirical, taken after his brush with authorities. Hail to the kingdom! Joanne has slipped her arm into Ben’s and is holding him above the wrist. Gently, but steadily.

“Considering the climate there, I got off rather easy,” he’d write my mother upon his return. “No jail sentence, no fine, no deportation proceedings (a common fate there)—they were just intent on confiscating my film.”