I once owned an olive-green deep-freezer, a modest version of the essential item in the giddy bride’s trousseau. My friends’ models were white, and three times the size of mine. I quite liked that the color and the size of my freezer distinguished it, and it fit my miniature kitchen. But even before the machine had settled in and was softly purring in its nook, a slinking question invaded my proud proprietorship . . . Did I need a deep-freezer?

(It was a bit like bristling for those almond bombonieres at the wedding reception. You couldn’t protest out loud, nor grab the sleeve of the server; you were dressed to showcase elegant nonchalance, not wrangle for wedding-favors with the couple’s faces printed on them (colour-coded for the bride, a quick burst of sentimentality). But the bombonieres were trendy on the Nigerian wedding scene, imported and therefore highly esteemed, and you were indignant if you were passed over and not given your own, indignant without knowing the subterranean reason why you were so deeply wounded. The sugared almonds would almost always end up in the bottom of your handbag in the company of lowly fluff and vagrant tic-tacs, much too sweet to be sincerely relished by the Nigerian palate. The point was you had got your bomboniere.)

The freezer compartment above my refrigerator was a neat hole that could fit enough food for two for the duration of a small apocalypse if one occurred in Eti-osa, our “local government area.” There was no use looking a gift horse in the mouth; the trousseau was a benevolent assemblage from both sides of the married couple, meant to please, to make my first home comfortable and make it clear that I was no “anyhow” bride from an “anyhow” family. (Not every bride got a deep-freezer). And, in the end, weddings and births will eternally be for owning what one does not need: five different dinnerware sets, fifty drinking glasses, an artificial ficus tree, and a fondue set. (What is fondue?) I wasn’t going to overthink the arrival of my deep-freezer.

Before too long the deep-freezer had become a bin I struggled to close. Spilling with solid elbows of blended peppers and tomatoes—i.e. Yoruba woman’s stew blends—soups-for-swallow, bloody guinea fowl parts, fresh snails, catfish, chicken, ready-steamed-moin-moin, portions of jollof rice . . . all of that crackled harmoniously with frost when I opened the box’s door. On some indefinite future date, I would make my mind up about the hoard, I decided.

It was only much later on, after I had rid myself of the freezer, that I admitted that the point had never been to eat the food. I wasn’t never going to turn down leftovers from family gatherings, the “I thought of you Yemisi, and you know they microwave so well” puff-puffs (Fufu microwaves beautifully too, by the way, retaining a soft elasticity, and gaining a hot moreishness, the kind that good swallow needs to carry into the depths of the stomach). The thought of microwavable puff-puffs and fufu was so comforting that it gold-plated my food bank; wherever I was, my mind could travel to it and get a brisk injection of happiness.

But the offer of food had to be accepted. There is starvation in Ethiopia, on autoplay in my head since childhood: whenever you left food on your plate, my mother warned that there was starvation in Ethiopia. (Nigerian starvation did not rank). Because those Arab children at the traffic lights near the Lagos Law school would not be begging if they had hoarded party-jollof in their freezers, you don’t throw good food away. You hoard it. Hoarding is the duty of every conscientious, sensible wife.

It was ridiculous. I was ridiculous. I can testify that not only was I giddy, I was levitating. I needed back-up for the ubiquitous pots of red lubrication that no newly wedded Yoruba woman with an iota of self-respect would unable to whip up in less than thirty minutes flat. I needed ewedu to go with my amala, and back-up ewedu is necessary because who wants to cook impromptu ewedu on a weekday? My titus fish oku-eko had to be present—washed, cut and bagged for upcoming deep-frying, savouring with gari and ice-cold water and groundnuts—in case a craving reared its head in the middle of a boiling hot night.

The point was: when the end of the world arrived, unannounced, as we all know it will—or when floods from Lagos rains swallowed the roads and I couldn’t drive to the market at Lekki Phase 1—I would be prepared, girl-scout prepared. And so it went on; I did not invest an iota of contemplation in a methodology for filling and emptying the bin.

Until our electricity supply disappeared for an entire month.

Our electricity was better than in most parts of Lagos, so we didn’t have a back-up generator. We also couldn’t afford one, and so the money went to true necessities. But as the days in that long month rolled oppressively past—and as the box stimulated emotions of disbelief, hope, negotiating prayers to God, and anger—what angered me the most was the abrupt loss of this previously phlegmatic personality, that lived in my kitchen and welcomed me with soft humming and shuddering when I returned the kitchen. Just days before, it was a personable living thing; suddenly, without notice, I was betrayed by its silence, and second by second, I was given notice in every waking thought, every dream, that my ice, in my box, was melting.

I could not shift my mind from the slow defrosting of its contents. My resolve didn’t thaw, though; that wicked creature “Hope” kept whispering in my ear: The electricity would return, NEPA will come back today… Through the length of muggy days with late sunsets and blistering afternoons, through silent nights pristine and clean of electrical chatter, with no 9 o’clock news reportage floating out of apartment windows, no static from the night guard’s radio. No Dekunle-Fuji struggling to escape from behind the door of the apartment, two floors down, where there always seemed to be a party on. The silence was dense with waiting, weighed down by everyone’s hope, as every part of that Lekki Epe expressway—that our transformer had previously animated over long days and nights—was tense with hope.

Meanwhile, my freezer was second-by-inching-second becoming an oozing, stinking watery nightmare, breaking my heart. There is no way to truly express the long, drawn-out, and torturous heartbreak of wishing back electricity in Nigeria. Sometimes I suspect that Nigerian resilience is connected to this NEPA torture.

Today . . . today . . . today. No, not today-o.

I believe I gave up hope—in the communal way we do, when it concerns NEPA—about two weeks into the month, when the aroma of frying meat pervaded the estate. This smell is the smell of defeat, of unanswered prayers, of preserving precious meat by long deep-frying into dark threads of salty meat. When the dense and delicious and disheartening smell of frying beef lingers after days of no electricity, you understand that your neighbors have given up, and so you too give up.

The experience took me back to the year at university, when a group of engineering students were building a freezer that would run on pig’s dung. We thought it was hilarious; why would anyone want that anywhere near their food? If we all had dung-run freezers, how would we breathe? But as my defrosting freezer released its last lungfuls of cold breath, thawing audibly as chunks of ice came off the inside and crashed dramatically to the bottom—as I would sometimes walk past, stroking the pristine creature and hoping that by some miracle my touch would bring back the electricity—I realized how foolish I’d been not to celebrate their genius staring me in the face. What I would have given for a pig’s-dung freezer, ensconced in a shack in the backyard with a padlock on the door to bar my neighbors’ urban snobbishness. That is, if I cared what they were thinking. I would not care to shield them from the assault of my bags of fuel; happy that my pigs’ dung—concrete and reliable—would be in reach, I would care for nothing. That was one genre of hope that would not disappoint.

What was the use of this stupid Nigerian electricity, that powered nothing and broke your heart? I would have lived my night life by candle light for a year and not breathed one ungrateful word if only my fridge and freezer could run on some alternative spirit. But the pig’s-dung freezer is interred in the Nigerian museum of Nigerian hope.

There are very few things as traumatic as throwing good food away; my God, what shame I felt, thinking of the Ethiopian starvation I have been worrying about since I was a child. And so, I swore to never own another deep freezer, a promise I have kept to this day. Who needs that receptacle of dead things anyway? That glorified morgue, that bottomless pit for food that we really really don’t want to eat? Who was it that said, very insightfully, that the deep freezer is where good food goes to die? I want to eat something fresh, something picked out of the ground, vibrant green, red, yellow, and sentient.

I suppose my uneasy relationship with deep freezers goes back to my childhood, to my mother’s purchase of a smoked bush rat.

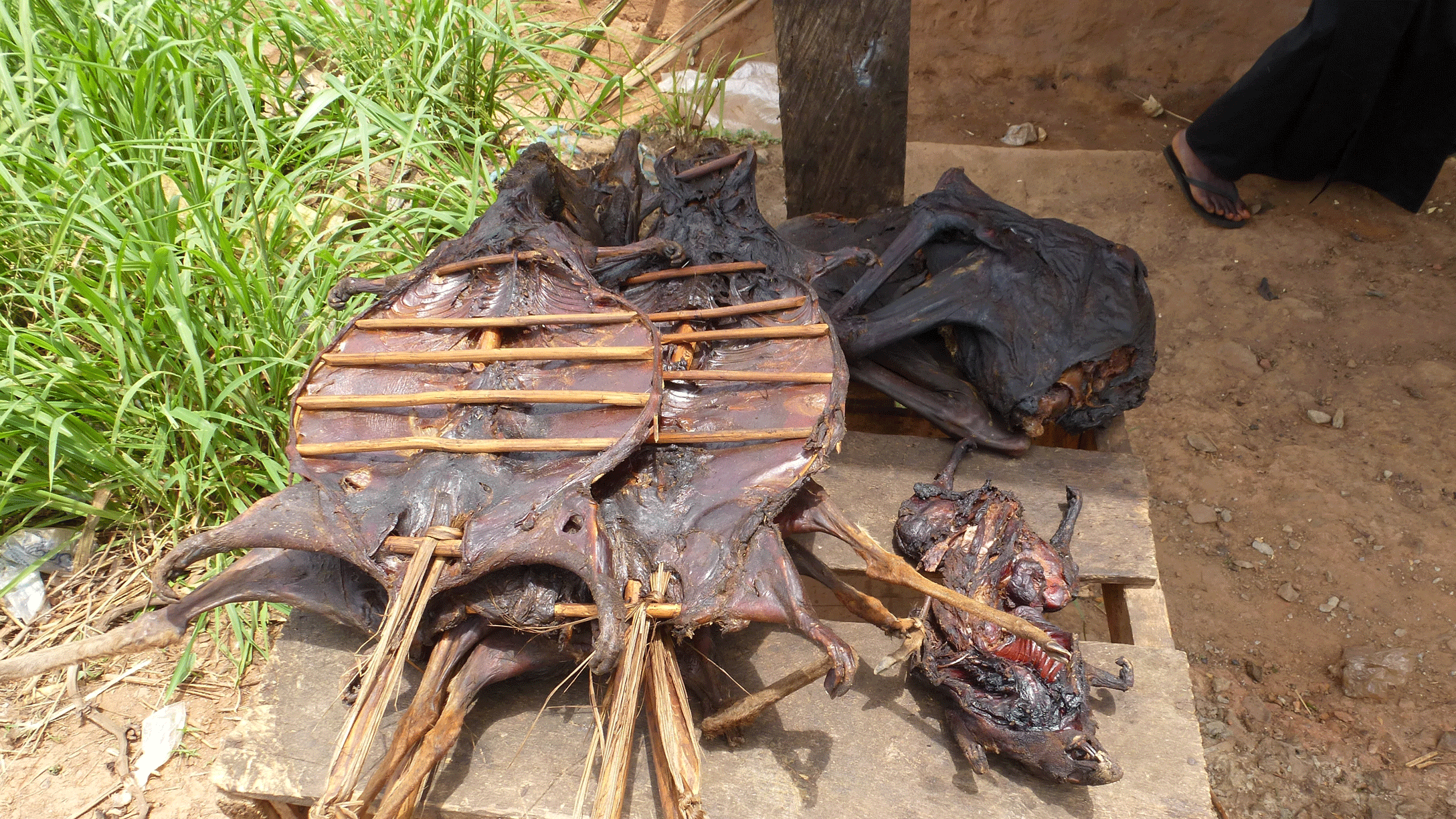

If someone arrives at your house with one of these smoked creatures as a gift, they must hold you in very high esteem, indeed. They are expensive. And it’s a triumph to buy a conscientiously-smoked cane rat (for cooking Efo riro or Ekpang or Egome). You can’t buy one in Lagos, in a supermarket or a city market. You have to be flying down some expressway between Ibadan and Ile-Ife, or between Calabar and Ikom, in some rural part of the country where tall bush flanks the road and people stand holding, at arm’s length, up for sale, freshly harvested corn, dodo-ikire, impaled porcupine, Afang, creamy bananas and plantains, and bush-ewedu. When you sight a potential buy, you have to slam your brakes like a madwoman and swerve onto the banks of the road. You have to have an expert eye to find the bush rat that was hunted with integrity and a humane trap, whose hidden parts were not ridden with pellets from a Dane gun. You have to smell out the kind of tree branches used in holding the rat’s body apart like a taut tent, since the branches affect the flavor of the meat. You have to know what concealed rot smells like. You have to be able to read the body language of the vendor. All this you do while also keeping your wits about you for attacks by armed robbers.

I’m not sure how my mother came to possess her own smoked cane rat, but the expression of death on its face terrified me when I saw it in the freezer. Cane rats are usually smoked with their heads still on, which most Nigerians don’t mind because some people eat the heads. If you mind, you are a wimp and must never say so.

(I mind.)

I was just starting school, and just tall enough to see clearly into the contents of the freezer. My mother’s deep freezer was the ideal Nigerian woman’s size. Not the size of the one in my trousseau, it was big enough to put me inside and close the door over my head (a thought, in itself, the subject of nightmares). I had no clear view into the contents of the freezer, but I had seen the animal being brought home and lovingly, reverently tucked into the cold dark interior. My mother said she noticed that I kept going the long way around the furniture, so as not to go near it. But this realization only settled after the fact of what happened.

When you are that age, I think, you don’t understand death but suffocation and darkness and cold, you can imagine; to see something with an agonized face in the freezer, a face that forces empathy, you can believe the creature is in pain, without knowing that it was dead. There was a time in the past when it wasn’t imprisoned, when it roamed as it liked; perhaps it was naughty, and the freezer was the naughty box, that creature so much closer to your size than adults. What if you, too, might end up in the box?

When my mother picked me up from school, on one of those first days, a teacher queried her whether we ate cats; if so, had we recently bought one to keep in the deep freezer? My mother didn’t put two and two together at the time, I think, and didn’t realize that the “cat” was her delicacy being hoarded for a luxurious efo riro. She just laughed; “Of course not.” But it came together another day, when my mother turned up at school and found that I had disappeared into thin air. My poor brother, only two years older, got his ears viciously twisted, but he could only confess that I had entered the car with some other children, and gone home with them, ignoring all his pleadings. (A driver and nanny had done the pick-up that day and hadn’t noticed the discrepancy, or must have presumed that a new child had been added on).

My mother took my brother home and then came back to the school, to wait in the hope that I would turn up. And I did, late in the evening, returned by the parents who had come home after work to find some strange child among their own children, eating gari and pretending to be one of them. Only then had my mother realized I had fled the house on account of the cat in the deep freezer.

Next, in Tempo: Kiang in the Taipei Underground, by Brian Hioe

Yemisi Aribisala