In a recent New York Times article Amanda Hess suggested that the rich and famous cheating parents caught up in the college admissions scandal wanted their kids in “elite” schools, and at any price, for reasons far removed from the ideal of a liberal education. The kids were props, used by their parents to excuse their own privilege, to cement their place in the “meritocracy.” The child’s degree—or the bribed simulacrum of it—would confirm the whole family’s right to its high status.

“More than faking their kids’ athletic or test-taking prowess, these parents have faked their own parenting,” Hess wrote. “They did not wind up raising enviable, academically extraordinary children, but they’ve fudged the results so they can drop ‘U.S.C.’ in conversations instead of ‘A.S.U.’” (One of the indicted parents, Mossimo Giannulli, specifically mentioned A.S.U. as an undesirable school in a wiretapped conversation with Rick Singer, the cheating and bribing kingpin.)

The question of “U.S.C. versus A.S.U.” in this piece was unclear to me; to what extent was Hess underwriting this hierarchy? I wrote to ask her, and she replied that she wished she’d had the space to elaborate in the piece. And for good reason:

I’m from a Sun Devil family. My mom worked at Arizona State… I don’t think any of the jokes about ASU are based on a real understanding of the kind of education you could receive there; it’s based on the number of people who can access that education […]

The same people who surely believe that every child should have access to a college education also make sure to rank some of those educations as enviable and others as embarrassing. The idea of an elite, high-class education must be hoarded by a select few, because if everybody had it, it would lose its value to the elite.

Which might explain why someone like Mossimo Giannulli might prefer to say, “my daughter is at U.S.C.”—though it doesn’t explain the ignorance that would support such a hierarchy in the first place.

When people are willing to drown themselves in debt and even commit literal crimes in order to obtain an elite college education for themselves or their kids, what, really, what exactly, do they they think they are buying?

Or selling. What are people thinking, who are selling an “education” that is actively harming a whole society; that wrecks the fabric of a city, that causes people to lose their grip on their conscience, their sanity; that makes them set so catastrophic an example, somehow both before, and on behalf of, their children?

Reaction to the admissions scandal has so far centered on the rich parents and their unworthy spawn, whose lawyers now prepare to spin a tale of misguided, but forgivable, parental devotion. No less a cultural authority than the playwright David Mamet wrote an “open letter” defending accused admissions cheat Felicity Huffman; according to him, “a parent’s zeal for her children’s future may have overcome her better judgment for a moment.” Except that the “moment” went on for months, according to court filings, and involved Huffman’s paying $15,000 to ensure that her daughter would have twice the time to complete her SAT exam that an ordinary, non-bribery-enabled kid would have. Also to hire a crooked proctor afterwards, who could change some of her daughter’s wrong answers to correct ones.

In any case, Hess is right: You can get an ultrafine education at A.S.U., which is an R1 university, positively bristling with Nobel laureates and MacArthur fellows. Walter V. Robinson, who led the famous “Spotlight” newsroom at the Boston Globe, teaches there. It’s wild to think anyone would be willing to blow a half million dollars to ensure a child’s admission to U.S.C. over A.S.U.

Anyone who has been to (any) college can tell you that the proportion of enlightenment to hangovers varies greatly from customer to customer. It’s something else altogether that calls for the half-million bucks.

Coming from a quite different angle—and on March 27th, the very same day as Hess’s piece—Herb Childress, in the Chronicle of Higher Education, asked: “How did we decide that professors don’t deserve job security or a decent salary?” (“This is How You Kill a Profession.”) Childress is one of tens of thousands of Ph.D.s in the United States who failed to find a place on the tenure track, and who were slowly forced out of an academic career as their prospects faded year by year in the academic Hunger Games, as this brutal process is not uncommonly described.

You might assume that people like Childress just “didn’t make it” through some fault of their own, but you’d be wrong. Over the last fifty years academic work has come to look more and more like indentured servitude: Grad students and postdocs are a species of flexible workers in a gig economy, toiling in low-paying jobs waiting for their once-a-year chance to play the tenure track lottery.

Please note that these are the very people who work in the “good schools,” who are compelled to “teach,” for insanely low pay—as low as a few thousand dollars per class—people like Mossimo Giannulli’s daughter Olivia Jade, a famous YouTube “influencer.” This lady’s dad paid hundreds of thousands to put her in the orbit of hugely educated, committed, job-insecure people like Childress. She, meanwhile, impishly bragged to her legion of YouTube followers, “I don’t really care about school.”

And yet scholars like Childress can’t let go of their romantic notions of the academy, and their sense of vocation, which can so easily be exploited; unfortunately they’ll agree to live the dream even at cut rates, as Childress himself openly admitted in the Chron.

The grief of not finding a home in higher ed—of having done everything as well as I was capable of doing, and having it not pan out; of being told over and over how well I was doing and how much my contributions mattered, even as the prize was withheld—consumed more than a decade. It affected my physical health. It affected my mental health. It ended my first marriage. […]

Like any addict, I have to be vigilant whenever higher ed calls again. I know what it means to be a member of that cult, to believe in the face of all evidence, to persevere, to serve. I know what it means to take a 50-percent pay cut and move across the country to be allowed back inside the academy as a postdoc after six years in the secular professions. To be grateful to give up a career, to give up economic comfort, in order to once again be a member.

Consider the benefits-free, pension-free pittance paid to the vast majority of people providing the “elite” education—who never saw a dime of all those millions in bribes—and a more complicated and larger picture than we’ve yet seen emerges.

I asked a very brilliant friend who attended Harvard to tell me about his admission there. He hails from an academic family of relatively humble origins, a family where the expectation was that the kids would work hard, go to college and do well. His parents taught at a big university and in those days one of the faculty perks was tuition for the kids—a full ride at their home institution, half elsewhere. But both of my friend’s parents were faculty, and so that meant a full ride literally anywhere, half from each, paid in full by their employer. Imagine this today!

He’d been accepted at a lot of places, including, suddenly and unexpectedly, Harvard—a longshot “fancy” school he’d added to the list on a whim. After spending a revelatory weekend at Oberlin, he’d all but made up his mind. But he went dutifully along to take a look at a couple of the Boston schools that had accepted him.

And I rode up to South Station and I found my way to the T—I literally could not understand the token seller’s accent—and got to Harvard Square. And it was nice, the dorms looked nice, the city was a city, I went to a record store and discovered that Doolittle existed and bought it.

Met some fun people, some good-looking people, went to a couple of real good parties, if not as good as the Oberlin parties.

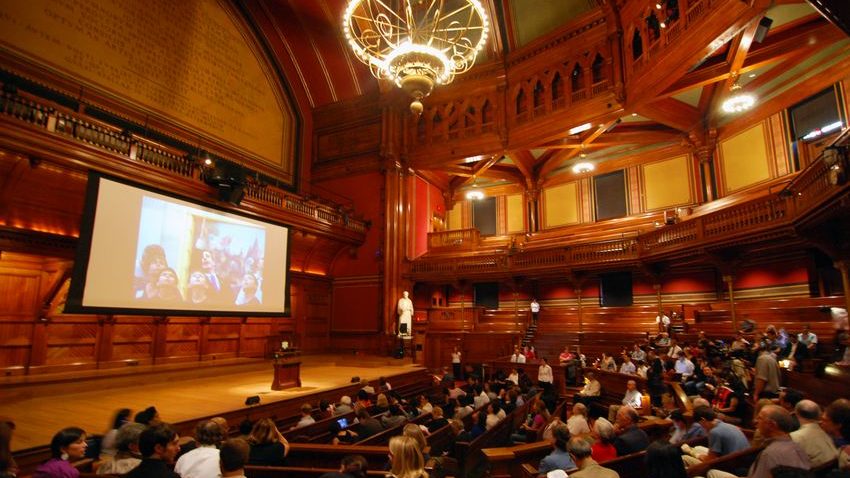

And then I went to sit in on a class. It was Foreign Cultures 48, The Chinese Cultural Revolution, taught by Roderick MacFarquhar (R.I.P.) It was in Sanders Theater, the huge dark wood theater at the end of Memorial Hall.

It was packed.

And I sat there, squeezed into a distant antique bleacher seat, looking down at the distant stage, and I listened as Roderick MacFarquhar delivered a lecture about how Chinese politics and historiography had to reckon with a problem: the Soviets could divide up their history between the figures of Lenin, the idealist who brought their new nationhood into being through revolution, and Stalin, who committed the brutality and crimes that went with institutionalizing and ruling the post-revolutionary order; but in China, Mao had played the roles of both Lenin and Stalin, founder and dictator, and there was no easy way for them to divide his career into the good and the bad.

But so I knew nothing about post-revolutionary China, or China at all, and not much useful about the USSR, and the lecture was totally lucid and powerful and—educational.

I wasn’t nearly as much of a paragon, but as a brown-trash “gifted” kid who came up poor and went to fancy schools I can easily understand how listening to this brilliant lecturer dazzled my friend, and changed the course of his life. This feeling comes to students anywhere, everywhere, in every school with a good teacher with time and attention to give us.

There was and still is something vital, something good and real, to want out of an “education,” something quite beyond the ken of the kind of people who would pay an SAT proctor to cheat.

Then there’s this other angle. I first went off to college already inured to the idea that I was involved in an economy; that we were trading. Everything had been made easier for the rich kids, of course, and it wasn’t their fault, all had been bought and paid for by their parents and grandparents, but also—a crucial thing—they had also lacked our luck; they lacked certain desirable qualities, qualities as randomly distributed as wealth, things with which some of us had won a different lottery, had skipped grades with and been celebrated for: the sort of “intelligence” that made school easy. There seemed to be a natural symbiosis in this structure, crazy and shameful as the whole business of “meritocracy” appears to me now.

But also like all college kids we mainly didn’t give a fuck about any of that and just got to be friends for true reasons, just loved one another. The rich kids happened to be able to teach the poor ones what fork to use and how to ski, and the poor and/or brown kids of halfway reasonable intelligence gave them books, new kinds of food and family, music and art, a view of the other side of the tracks, new ways to have fun. We poor ones brought, say, a taste for Lester Bangs, arroz con pollo, Brian Eno and Virginia Woolf; they treated us to foie gras and Tahoe and big old California cabs on our 18th birthday. Gross, right? Really gross. But the (grotesquely mistaken) idea was that we were bringing each other into a better world, a different world, and a little at a time the true, good world would finally come.

This may sound a bit tinfoil but now I suspect that the problem may have been, all along, that all the college kids started to realize together (as I think they are still) that there was something sick at the roots of this tree of knowledge as it was then constituted. Strangely, dangerously healing, egalitarian ideas began to take hold; demographics changed, and the country began to move to the left. The 90s was the era of the tenured radical on campus, and the culture wars grew white-hot. Al Gore was elected president, and was prevented by the merest whisker from taking office. Even a barely left of center President Gore would have made things a little too parlous for the powers that be, who are on the same side as the Giannullis of the world.

Hess told me that some people think there’s one kind of education within the purview of everyone willing to work to get it, the “embarrassing” kind, and then there’s another kind that is luxury goods, strictly for “elites” from “elite” institutions—however corrupt the latter may be—served tableside by an underpaid servant class.

But the egalitarian view of education and the luxury view are mutually exclusive. Pulling up the drawbridge around your ivory tower only cuts it off from the larger world, which alone can provide the intellectual atmosphere in which a free society, and its academy, can breathe and thrive. Power wants its “meritocracy”: thus the eternal cake-having rhetoric around higher education, the queasy mingling of “exclusivity” and “diversity.”

Note too that the ruling class protects its interests as starkly on the fake left of the centrist Democrats as it does on the right, where the Koch brothers have long bought professors like they were so many cups of coffee. In Jacobin, Liza Featherstone’s bracing denunciation of the noisily multilingual, Harvard- and Oxford-educated Democratic presidential contender Pete Buttigieg addressed this centrist hypocrisy plainly (“Have You Heard? Pete Buttigieg is Really Smart”).

The professional-management class (PMC)… tries hard to make their children “gifted” and to nourish their talents, an effort that is supposed to culminate in the kind of august institutional validation that [Buttigieg] has enjoyed… Smartness makes some people more deserving of the good life than others. Smartness culture is social Darwinism for liberals.

So the problem we’re looking at turns out to be a political one. It’s obvious enough that the intelligentsia of the United States finds itself reduced to literal servitude. Writers, professors, even the votaries of STEM, doctors, scientists and engineers, increasingly play the role of servants to the ruling class, who are systematically diminishing their roles, their numbers and their economic and decisionmaking power, concurrently and on all fronts.

In government, in the current administration, experts are made explicitly subservient to cretins with almost miraculously inadequate credentials. In the press, hedge fund managers who’ve never read a book outside of Atlas Shrugged are stripping the fourth estate and selling it off for parts. In the academy, administrators who’ve never taught a class starve the adjuncts, even as they themselves enjoy walloping six-figure salaries and exit bonuses.

The American intelligentsia is also in the process of being strangled in its own citadels with the aid of rampant both-sides-ism.

In the New York Times alone, unqualified writers like Bret Stephens, Bari Weiss, David Brooks and Thomas Friedman are permitted to style themselves “public intellectuals” despite their permanent and boggling inability to form or defend a cogent argument. This has the double effect of discrediting newspapers and the newspaper business, and devaluing the profession of journalism. And the independent voices that would once have challenged such poor work amid a mighty chorus must increasingly fight to make themselves heard.

To watch Donald Trump, who is an imbecile, boast day after day of his own intelligence and how well he did in school, to hear his followers yabber on about “protecting Western Civilization” when what they mean by that is plain white supremacy, is to arrive at the bottom of the fiery slide to damnation that began with George Wallace’s inane insults about “pointy-heads,” Reagan’s aw-shucks Morning in America Arms Sales Spectacular, and Dan Quayle explaining how to spell “potatoe.”

What there is to protect isn’t what they call Western Civilization, nor even what used to be called Western Civilization. But there is something still to protect, and even to fight for; a teenager in a crowded old auditorium, listening for the first time to a university professor speak, and entering almost unconsciously into the vivid light of a changed world.