“So this one is really fascist,” Paolo said, applying some solvent gel to the paint on the dirty wall. Around us, well-dressed couples walked their dogs or pushed strollers. “We gotta get rid of this.”

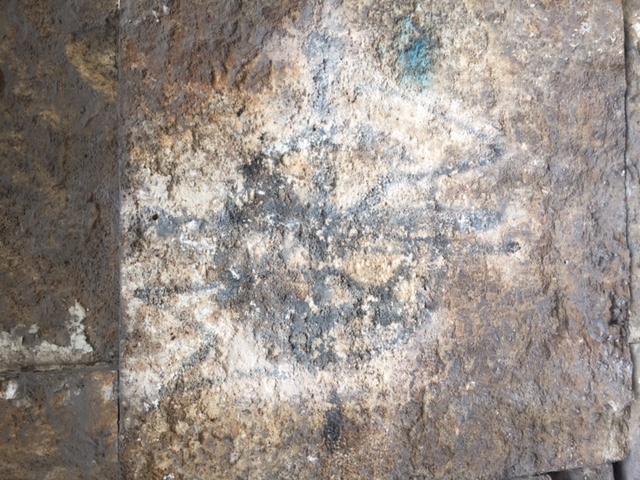

It was around 9:00 on a brisk Saturday morning, in my neighborhood of Monteverde Vecchio in Rome. The graffiti was a cross inside a circle, apparently a pagan “sun-cross.” Above were the letters CML, the initials of Commandos Monteverde Lazio, a fan group of S.S. Lazio, a Roman soccer club notorious for its ultra-right supporters.

Paolo is short and has a smooth, oblong face. His bowl-cut seems composed of exactly 50% brown and 50% grey hair. He resembles a Renaissance prince; not the one who was to become king, but the earnest third brother who busies himself with administrative duties.

“I’m guessing you’re not a fascist,” I said.

“Well, yes, obviously not, but even if I were I’d want it gone,” he replied. “For me it all comes down to legality. If you want to express some sort of political idea, there are other means—hang a banner from your terrace, put up signs, get permission to paint a mural. But not like this.”

After letting the gel set, I sprayed the graffiti with water and scrubbed it hard with a wire brush. It had been written on a once-white pillar, discolored over the years with grime and dust. When I was done I took a step back, and swore; I’d left a perfect white impression of the graffiti in the brown background.

Right now, Rome is a disaster in the colloquial sense, and has real potential to become a disaster in the public-health, financial and political sense. When buses aren’t late, they spontaneously combust. Even areas around famous monuments are unkempt. And everywhere, it seems, there’s garbage — broken bottles, abandoned furniture, whole dumpsters tipped over and spilling ruptured trash bags. Giant seagulls migrate in from the coast to feast, along with families of wild boar. The city’s current state of disrepair has become an empirical fact, acknowledged by everyone who lives here, in the same way that others might say “Seattle is rainy” or “Tucson is hot.”

Who’s to blame? The simplest answer is mismanagement by city government, especially the current mayor Virginia Raggi, a member of the populist Five-Star Movement. Under her administration, Rome plunged from 67th to the 85th on Italia Oggi’s annual “Quality of Life” list for Italian cities.

But back in 2010, long before there was talk of things like closing Rome’s public schools for health risks, Rebecca Spitzmiller, an American professor at Roma Tre University, started cleaning the graffiti off of her own apartment building. She felt “clinically depressed” by the dirtiness of her adopted city, she told me. With another American in Rome, Laurie Hicks, she organized a cleanup of Villa Borghese, Rome’s most famous park. An Italian woman, Paola Carra, joined these two “menopausal blond Americans,” and so was born Retake Roma. Beginning with group cleanups of notable Roman sites, Retake evolved into a movement with volunteer chapters around the city, each working to beautify their neighborhood. The group numbers more than 2,000 regular volunteers, and the concept has spread to dozens of other cities. Spitzmiller received the Medal For Merit, Italy’s version of the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

And yet with all this, Rome feels more degraded and less hopeful than ever. Is Retake working?

“We’re trying to change the culture here,” Professor Spitzmiller said. “It’s not a math problem.”

I have always kind of liked Rome’s laid-back atmosphere. Is Retake merely crotchety neat-freakness in a city with worse problems—a city whose municipal dump literally caught on fire? The garbage crisis is undeniable, but I enjoy soccer-fan graffiti and mouldering buildings, and the way you can drink a beer in a piazza without getting hassled by the police.

Paolo, who runs the Retake chapter in my neighborhood of Monteverde, arrived a few minutes before the appointed hour of 8:30, his little sedan sagging with buckets and tarps and a giant “Retake Roma” flag. I would later learn that he is renowned amongst Retakers, both for his enthusiasm and for driving the volunteers like a forest-firefighting crew.

I was paired up with Alessandra to remove a tall, looping design from the side of a wall. She was a middle-aged woman who dabbed gel on the paint with one hand and smoked thin cigarettes with the other. The smoke mingled with the cocktail-olive smell of the gel, and I got dizzy after a half-hour of brushing with no end in sight.

“Unbelievable,” I said. “Some dumbass took five minutes to do this, and now it’s going to take us three hours to clean up. Man, if he were here …”

“That’s the thing with Retake events,” Alessandra replied, smiling grimly. “You start out with all these lovely thoughts about community and hard work and civic duty… and then by the end all you can think about is hurting people.”

At lunchtime, the Retake ended. Walking down the street, I paused to look back. The shadow of the tall graffitti was quite visible, the dumpsters still overflowing.

“We’re not just trying to clean the streets,” Paola Carra tells me, sipping her espresso. We were sitting in a bar in the periphery of Rome with two other Retakers and an urban graffiti artist; they’d just finished a panel discussion on the “Power of Positive Thinking” at the nearby high school.

“We’re after a thought revolution, in which every person intimately realizes their responsibility to give something back to their city.”

“Even if we had a highly efficient city government,” she continued, “citizens still need to be—and this is what we’re after—aware that the actions of each individual have consequences for the environment we all live in. A city government isn’t enough to make a city that works.”

I ask whether the nine years since Retake started have resulted in change.

“It’s true that the city is falling apart. It’s true that there are big problems that can’t be solved by individual citizens,” Paola replied. “But schools call us to give talks, more and more people are coming together. We’re sowing the seeds for something.”

I decided to go to a Retake in a wealthy neighborhood. Part of me expected dozens of well-dressed people in dishwashing gloves, ready to sandpaper microscopic imperfections off their apartment buildings; the other part expected nobody to show up at all.

When I arrived at around 2:30 on a Sunday afternoon, Fabrizio Mencaroni, head of the Prati group, stood near the top of the bridge as a misty rain blew around him. He was an imposing character, his Facebook timeline an endless photo-documentation of wrongdoing in Rome: trash bags left on stoops, cars parked on the sidewalk, even a teenage boy lounging on four subway seats. With his heavy coat, beard, and long gray hair swept around his neck like a scarf, he resembled a mountain man.

Before I’d even reached the top of the stairs, he informed me the Retake was cancelled. Too difficult to paint with the rain. He’d shown up to warn off anyone who hadn’t seen the Facebook post twenty minutes before. Before that, he’d gotten into an argument below his apartment with a well-heeled gentleman who’d been tossing his recycling into the garbage dumpster. When reproached by Signore Mencaroni, the man replied that someone at the garbage plant would sort it out. Mencaroni reminded him that garbage is mechanically sorted, and the man snapped back, “I pay my taxes, it’s not my problem.”

“If they don’t fine people, people won’t stop doing these things,” he growled.

I asked him if Prati, being a wealthy quarter, had fewer or more Retake participants than a more working-class one. He admitted attendance was low at Prati events, but he chalked that up to many of its residents being old, rather than rich.

At that moment Riccardo Schiavon, head of the Parioli group, ambled up. He seemed the opposite of Fabrizio: late-twenties, with a scruffy beard, and long hair worthy of a jousting champion. He had just returned from a Sunday lunch with friends, and was still wearing his shiny wingtips and dapper wool jacket. He greeted us in that singsongy, almost Viking-like accent of those from Northern Italy.

We walked across the bridge towards his car. Riccardo said that when he moved from his native Milan to Rome last year, he’d been disgusted by the amount of garbage and decay, and even more disgusted by the apparent apathy of his new neighbors. On that, he completely disagreed with Fabrizio.

“This is a particularly Roman thing,” he said, the olive-green Tiber swollen beneath us by the rain. “The more money you have, the less interested you are. It makes me angry that you have millionaires in these apartment buildings, and yet the outside is filthy. Jesus, you pay people to clean your apartment, why not pay someone to clean your sidewalk?”

We paused in front of a discarded pink blankie, lying on the ground in a puddle of brown water.

“Normally I’d pick this up,” Riccardo says. “But I’m wearing my nice clothes and I don’t want to get them dirty.” The word “hypocrite” surged out of my mind’s gate, but I had to admit he had a point. Retake addresses something so intimate and so constant that you can’t possibly get everything “right” all the time.

In the car, a shiny new Fiat, I had to get into the backseat, as the front was already occupied by dirty brooms and shovels and rakes. Riccardo drove up the river and turned right into the heart of northern Rome, past blocks and blocks of elegant apartment buildings. He slowed down near an intersection, and pointed out an emerald-green beer bottle lying next to the STOP sign.

“You see, that’s on citizens. Yes, it’s on the city for not fining people. And for not putting bins here. But in the end, someone chose to drop that here.”

We parked at in a small terraced area near the Museum of Modern Art, and walked to the Piazza Winston Churchill, above the Piazza Simon Bolivar, each with a statue of its titular statesman.

“The English sometimes give money for the upkeep of this Piazza,” Riccardo told me. “Right now Venezuela can’t help too much, for obvious reasons.”

He led me to a small wooded spot, the size of maybe half a basketball court, in between the two piazzas.

“Look how dirty it still is here,” Riccardo says. There was a whole assortment of trash: a broken loveseat, a filthy cupboard, splintered umbrellas, discarded rugs and heaps of broken bottles.

“We did this all yesterday,” Riccardo said, sighing. “Do you know hard it is to move all this wood? It’s not like we have chainsaws or trucks.” He gestured towards a dead tree, thick as a telephone pole, that he and his group dragged out of the center of the area. “Now what are we supposed to do with it?”

The dumpsters behind us were still full of grass trimmings and sticks from yesterday’s Retake. Above us, the chic cafe of the museum was tapering down lunch service.

“So why’d you make an ass like this?” I asked, forming my thumbs and index fingers into a wide circle, the Italian way of saying “work your ass off.”

“If we clean all of this stuff out, hopefully people won’t see it as a place they can just dump stuff.”

One of the guiding principles of Retake is Broken Windows Theory, the increasingly-criticized idea that cracking down on small-scale disorder or crime, like graffiti or public drinking, will prevent more serious stuff from happening. Rebecca Spitzmiller still believes in Broken Windows (“I’ve seen it work with my own eyes,” she told me). But for all I had seen of Retake, it didn’t seem like Broken Windows at all. Broken Windows is about fixing the small to prevent the large.

Maybe I just needed to see something bigger, more important, a Retake so grand and thorough that I’d finally see a better future for Rome reflected there. I signed up for a piazza clean-up in Garbatella. This neighborhood is known for its beautiful public housing, in the “Garden City” style of octagonal buildings, originally built to house workers constructing a new port for Rome.

I arrived at the Piazza Benedetto Brin at 8:30 on Saturday morning; it seemed a mess, with a crumbling, dripping fountain in the center, and the edges strewn with garbage. Gianni Stifano, the head of the Garbatella group, was trim and graying, with wraparound sunglasses and sweatpants; there was something of the weekend warrior vibe about him. Gianni told me that this Retake was merely a touch-up. AMA and the state archaeological service had apparently cleaned the Piazza a few weeks before.

“It was practically useless before they came. If we hadn’t pushed them, they wouldn’t have come.”

They put me to work removing adhesives off the metal roller-shutter of a nearby business—these are stickers advertising businesses like movers and roller-shutter repairmen. Technically, they’re abusivi, meaning placed without a permit, but they’re so small that businesses pay people to stick thousands of them around the city.

The flexible plates of the roller-shutter rippled and rattled with every stroke.

“What’s the point?” I muttered to myself. “Who cares if there are some fucking stickers on a metal door that’s rolled up during the day.”

I moved to painting duty. A group of us worked on a metal railing, painting over the rusted and scratched spots. It was pleasant, working together and chatting as the sun rose up and shone off the freshly-lacquered fence.

More and more people, noticing my reporter’s notebook, came up to talk to me, wanting to express how Retake was like a drug, the most inspiring thing they’d ever seen with the most inspiring people they’d ever met, how this little movement had become something big. As I politely scribbled their quotes, I had the strong feeling that I was different, that I was not really a Retaker, that whatever joy this work brought to them I did not share.

A few days later I called Rebecca Spitzmiller to ask whether people like me were a roadblock to achieving Retake’s goals. The mess in Rome is, supposedly, everyone’s problem. But if everyone doesn’t become a Retaker, what’s going to change?

“I think about that a lot,” she said. “We don’t expect to convert everyone to active Retakers. We want to make everyone aware of these problems. So that maybe next time, they don’t throw their garbage in the street. Or they have a talk with their kid when they find a can of spray paint in his closet … In the end, democracy is our best hope. And people need to realize that in a democracy, yes, they have privileges and rights, but they also have duties.”

The next Sunday after Garbatella, my duty was, again, removing adhesives. This time I was in Monteverde Nuovo, the neighborhood adjacent to mine. Paolo, of course, had come to help out, and we attacked a psoriatic streetlight pole with our wallpaper scrapers.

Later the head of the group, Donato Sciunnache, called me over to a large apartment building whose white wall was covered in graffiti. Donato is a Roman Jew, who took up Retake after a childhood spent in Hashomer Hatzair, a Zionist-Socialist scout movement. He’s a big grizzly bear of a guy, who brings a power-sprayer to blast graffiti off walls. Luckily, for me, that would mean no scrubbing. We chatted as we applied solvent gel to the black and blue squiggles. I noticed him sniffling all the while, and asked why he hadn’t stayed in bed.

“It’s early, I have a cold, I have two kids at home,” he explained, cranking up his power-sprayer. “I have more ‘important’ things to do. But again, I go back to scouts, and the idea of being an example for others … like my kids.” With that he put on carpenters goggles and turned the sprayer onto the wall. It was addictive to watch, like a tattoo-removal video on Facebook, as the paint vaporized and left behind only an ivory-white wall. By the end you wouldn’t have known there had been graffiti on it. Some of the residents of the street stopped and thanked us, saying they had always wanted to see those ugly scrawls disappear.