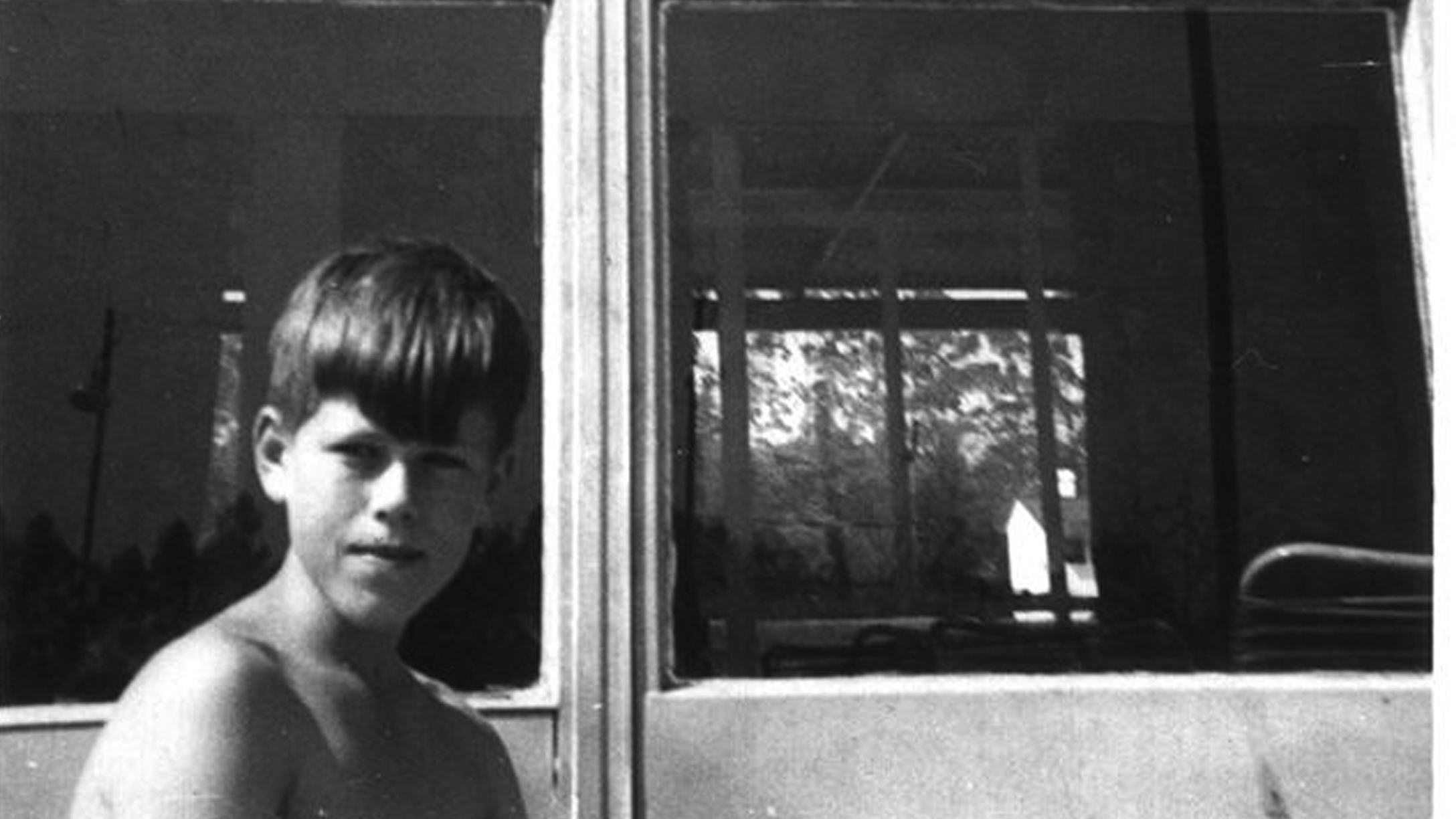

I was born in Blantyre in 1951, in the old hospital on the hill at the far southwest of the town up by David Clement Scott’s church, before they built the Queen Elizabeth Hospital in Chichiri. We lived in Limbe, up Mpingwe hill from Churchill Road—my parents, my older brother Simon, my invalid sister Vicky and Tom the dog. We moved down the hill to a house at the top of Churchill Road, and this is the house I grew up in until I left Nyasaland in 1964.

My father was manager of the Gallaher Tobacco branch in Nyasaland. He had been in India before and during the war, with British American Tobacco. My mother, a war widow with a daughter of six—my half-sister, Pam—came out to join him in about 1948, travelling by ship to Angola and then in a long and circuitous path by rail to Nyasaland. They were married in the Anglican church next door to the club in Limbe, by Padre Hand.

The Gallaher factory was a little downhill from us, on the other side of a narrow, curved avenue lined with tall jacarandas which gave access to the big, rip-roaring ERF lorries (or “Eriffs” as we called them) hauling bales of tobacco up from the auction floors a few hundred yards down the hill. There was a raised dock where they offloaded these massive, hessian-covered blocks of tobacco, and a slide of polished concrete about forty feet long which plunged from the dock down into the cavernous, echoing main floor of the factory where men loaded them onto “grovens” (don’t ask, I have no idea where this name came from) and raced them off to another part of the factory. Naturally, we kids couldn’t resist this accidental playground and spent many a morning during tobacco season riding the rough, bitter-smelling bales three-abreast down the slide like dodgem cars. Riding the grovens was fun, too. No doubt this was less of a lark for the harried workers, but I don’t remember them minding.

Sometimes on Sundays when the factory was empty we would sneak in and run around its suddenly silent halls. You could get in on the Siemsen Road side through a drainage tunnel, which was big enough to stand up in and full of bats. There were a couple of big machines inside—big enough to take up most of the rooms they occupied—that had something to do with packing or drying tobacco. They had wide metal conveyor belts like chain mail to carry the tobacco through, and you could crawl along these through the guts of the machine, a little nervous that they might spontaneously start up and chew you to bloody shreds. Down the road towards Abegg’s shop, on the opposite side of the road, there was a big warehouse where the bales were stacked to the roof. We used to climb up there and shout taunts at the Indian man who managed the place, whom we called Mr Babu. No doubt he thought us barbarians, which, of course, we were.

To me this place was Eden, and it seems even more idyllic through the rose-coloured glasses of sixty years on. Ours was a big brick house with high gabled roofs of green corrugated iron and a khonde of pink terracotta around three sides, set in an acre or so of lawns and garden cut off from the world by a wooden fence on the factory sides and on the others by a high juniper hedge. (With the aid of a ladder you could actually climb the hedge and sit on top). There was a thatch-and-pole “summer house” at the bottom of the garden (at least until it collapsed one windy, rainy day after being eaten by white ants), and a paddling pool by the back fence under the jacarandas where granadillas and cape gooseberries grew. A sort of Victorian gazebo stood on the other side of the house, made of brick pillars and entirely covered with roses, honeysuckle and other greenery. There were two big peach trees, two spreading avocado pear trees ideal for the building of tree houses and the stranding of cats, two very tall Christmas-tree pines, a hibiscus outside our bedroom window and a massive, completely unclimbable Spathodia on one of the front lawns.

Across the street on the other side by the factory where old Sand the gardener lived, there was a mulberry hedge and a paw-paw tree. If I ever pined for guavas, they were to be had in abundance down the road at my friend Paul Myers’s house (later the Johnson Hills), across the road from Abegg’s; and as for mangoes, there was a good tree up the road on Harper Avenue where the best friend of my early days, Claire Simmons, lived. She tempted me, you might say, and I did eat.

Alas, the glorious idleness of infancy can’t last forever, and at the age of five, after a period at Mrs Knowles’s nursery school in Blantyre, I began school at La Sagesse Convent, a stone’s throw from the house up on the other side of the Zomba road, under the gentle gaze of Sister George, first, then Sister Sylvester, and in the third year by the irrespressible American, Sister Henrietta (who, as I once saw, stealing a glimpse under her wimple, had long brown shiny hair reaching far down her back). Tiny, elderly Sister George taught us a few simple words of her native French. Stern Sister Sylvester’s strong suit was arithmetic. And as for Sister Henrietta, I was too busy admiring her, I think, to remember much of what she taught, but I seem to remember there were poster paints involved. Every month, the best performing student of each class was awarded, in a ceremony in the assembly hall, a pink ribbon inked with the word H-O-N-O-U-R, and wore it safety-pinned on his jersey, like a gymkhana horse with a rosette.

The Country Club Limbe was really the centre of our social life, and especially for my father. On Saturdays he would take us down there quite early in the morning, stopping on the way to get his post out of box 23 at the post office and, usually, to pay a visit to the Standard Bank opposite Kirkaldy’s, a sort of hardware shop. There were two bars at the club, the only open one at this early hour being the one with the sign over the door: Gentlemen Only. It was a long bar of dark wood, with a brass foot rail running along its length. Claire’s father Sam Simmons would be there, and they would spend the next hour or two quaffing Castle beer, smoking and playing snooker in the dim, curtained rooms adjoining the bar. Sadly, though I longed to play this game, children were reckoned too likely to rip the cloth, and we could only sit and watch the grownups stretching over their cues across the brightly lit green baize, their fingers yellow with nicotine. It cost money, too, of course —you had to feed the electric meter which provided the light —and my father, with (by this time) five children to take care of, was apt to grumble a bit when asked to part with any of it.

By eleven or twelve o’clock the car park outside, and the jacaranda-lined avenue down its middle, were thronged with cars—Studebakers, Chevrolets, Nashes, Fords, Chryslers, Plymouths, Pontiacs—with the white-walled tyres, muscular chrome bumpers and flashy rocket-ship fins that were the style of those rather vulgar times. (American cars were, by and large, preferred, though my father, who had the then traditional English distaste for almost anything American, drove a Humber Super Snipe—number plate BT5945—then a series of Vauxhalls. If he ever won the pools—and he filled in the coupons assiduously every week—he was going to buy a Rover or a Bentley. As for my mother, she drove an old black Hillman Minx, at least until my father surprised her with a Morris Mini station wagon for her birthday—it was, I was told, the first Mini in Nyasaland, and cost £600).

By this time, most of the wives would have arrived and the men had leaked reluctantly out of their male-chauvinist seclusion into the brighter and more public bar, a sort of skylit patio in the middle of the club. We children would drift in occasionally to beg fourpence for a bottle of Coca Cola or a Crunchie bar. (The Blantyre dentists, Mr Halford Ness and, later, Mr Newsome—or Gruesome Newsome, as my father called him—no doubt enjoyed a bustling trade). If things were particularly raucous and the grownups couldn’t tear themselves away, we might be lucky enough to get a meat-pie from the kitchen, on a little white china plate bearing the “CCL” monogram in a blurry blue ellipse, or chips with vinegar. I used to pester the waiter, Benson, to let me try on his fez—a reddish purple one with a sort of stalk in the crown, somewhat like those worn by the KAR.

Sometimes on Saturdays there were cricket matches. My father, in his youth, had been a champion in almost every sport known to man (or Englishman, anyway). There was a shelf of silver cups in the living room to prove it. He had been a keen cricketer, though by this time, in his forties, he reckoned himself too old to play and usually only umpired now and again. Occasionally, the CCL side would play away, at the Blantyre club, a rather bigger and grander affair than the Limbe club, or one of the two Indian clubs, or Cholo, or Mlanje, and Dad would drag us there to watch. In the home games we would sometimes be deputed to man the scoreboard.

On the raised ground behind the scoreboard were the tennis courts, and a beautifully kept bowling green where elegantly attired older members — even the ladies wore hats, I seem to remember — were occasionally to be seen sedately rolling. There were three or four red-clay tennis courts, each with a tall umpire’s chair painted dark green, and a stand behind and above for spectators.

At one time, which I can only dimly remember, there had been a tiled swimming pool behind the bowling green, but this was superseded by a new, larger pool. It cost, I think, threepence or fourpence to get in, through a gate in the wire fence where a khaki-uniformed character known to us as Shorty Pyjamas sat in a little straw hut dispensing tickets from a roll. Shorty was a friendly man but took no guff, especially from kids.

You had to watch out for water beetles in the pool, especially early in the day. These hardy beasts were apparently immune to chlorine. They fizzed around in groups on the surface of the water, furiously like little dark beads of sodium, and could deliver a fairly nasty sting – though nothing like as bad as that of the water scorpion, as I once discovered to my extreme discomfort when one somehow found its way inside my “cozzie”.

On one side of the pool was a lawn for sunbathing; on the other side was the so-called Dog Box, the clubhouse for the golf course beyond it, with yet another bar. You could buy Coke, Fanta or Miranda through a little window which gave on to the concrete slab outside.

The golf course was a nine-holer whose first hole, a par three, ran across the other side of the Dog Box and the practice green beside it. The second hole was a long par five on which my father boasted of having once driven his ball, down the threadbare, sloping fairway, four hundred and twenty yards, almost into the little brook which crossed it. On the far side, behind hedges, were houses, including that of my father’s friend who rejoiced in the name of Bunny de Grandholme, and his pretty wife. There was also there a two-storey house with actual stairs—a cause of great excitement to us kids, who had rarely seen houses other than bungalows and found stairs most strange and fascinating.

When very young, we had a nanny, Labson, who played the guitar and made sure we didn’t get into too much trouble. He also had a wind-up gramophone on which he played 78s. The only one I can remember was a song called “Teddy Bear’s Picnic”. No doubt it got broken fairly quickly, as these old records were as fragile as china. On my Dad’s real gramophone in the living room you could play LPs at 33rpm, and these didn’t break.