Telford’s Change, a BBC TV show about an international banker, was a hit when it came out in 1979. As Britain teeters on the edge of Brexit, it’s quite striking how closely the show prefigures the arguments being bandied about forty years later.

At the time Telford’s Change hit the (very small) screen, Britain had only been in what was then called the EC for a few years. The UK was still repaying a humiliating loan taken during the bleak years of the mid-1970s when James Callaghan’s Labour government had gone, “cap in hand” as the Tories grimly phrased it, to the IMF—a fate usually reserved for “third world” countries.

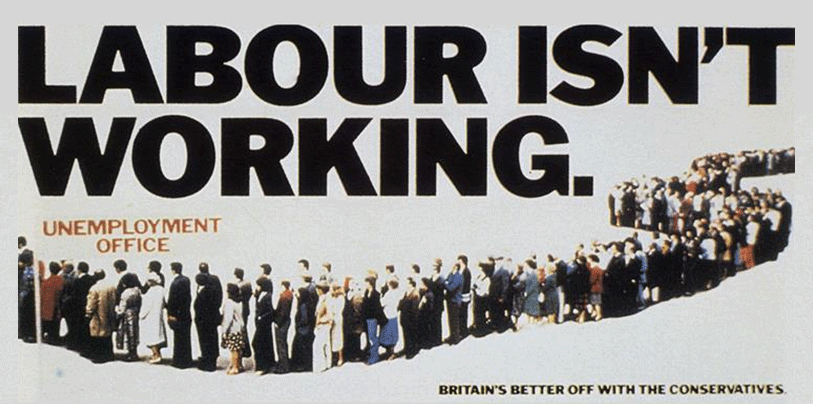

With more than a million unemployed and inflation still rampant, the economy was a mess, and the Labour government was on the verge of being soundly thrashed by Margaret Thatcher and her henchmen. The Tories were helped by the pioneering advertising agency, Saatchi & Saatchi, with its slogan “Labour isn’t working” and a picture showing an alleged unemployment line consisting of the same 20 or so Young Conservatives, photo-edited into a Depression-length queue outside the dole office. (This was the first time a political party in Britain used an ad agency in an election, which the Labour Chancellor of the Exchequer, Denis Healey, derided as “selling politics like soap-powder”).

Mark Telford is the star rainmaker in a City firm. You can tell he’s a jetsetting bigshot partly because he’s in a sharp-shouldered suit with a pay-phone pressed to his ear in an airport somewhere in Europe, telling his wife that he won’t be home tonight after all because he’s got to go to Brussels to sell a big loan to a French multinational. Also because of the “sophisticated” soundtrack, composed by Johnny Dankworth (the coolest of jazz musicians, and the husband of Cleo Laine.)

The giant blue-chip French firm is set to build its first factory in the UK, right across the Channel in Dover, for the impressive sum of ten million pounds. Telford knows the chances of beating out the Frenchman’s continental bank consortium are slim.

While he might sound like the very model of a malefic merchant banker, Peter Barkworth plays Telford as a sympathetic character. He’s obviously very good at international banking, fluent in French and German, a master of the business lunch, brimful of charm but at the same time shrewd and, in his smooth, gentlemanly way, a hard bargainer, and ethical with it. The eyebrows of the knowing Gallic industrialist to whom he makes his pitch testify bushily to a grudging respect for this competent Englishman, even though both know they’re just going through the motions.

The fact is, Mark Telford is fed up with the fast life. He does not deceive himself for a moment that it is the least bit glamorous. Rather than revelling in all the moving and shaking, he is stoically, dutifully, enduring it. Naturally, his flight back to Heathrow is canceled. He tries to take the boat-train but there’s bad weather. Can he still make it home in time for his wife’s dinner party tomorrow? Yes, of course.

When the ferry reaches—coincidentally—Dover, Telford takes a stroll around the harbour in his suit with the flared trousers, with the wide tie and cuban heels, and, as he helps a local yachtsman cast off for Boulogne, you can see in his horizon-scanning gaze, and hear in the suddenly gentle Dankworth soundtrack, a yearning for the quiet life. From today’s point of view, this is the fulcrum of the story: the quiet beauty and tranquillity of “home” balanced against the helter-skelter excitement of commerce with foreigners in the European Community.

Telford stops off at the local branch to cash a cheque and see if it has a manager capable of servicing a large multinational client, and here he gets a pleasant surprise: the manager is the same man who taught him the Elements of Bank Managing when he was but a bright-eyed trainee fresh out of school. Tom something, obviously. Tom is a self-styled dinosaur. He’s the British equivalent of an Eisenhower Republican, the relic of an earlier and worthier age.

“I’m not a manager”, he sighs, “I’m a bloody salesman. Look what they want me to sell: insurance, hire purchase, stocks and shares, even holidays”.

He does not think it’s a good idea to blandish customers into borrowing for consumption.

On Tom’s urging, Telford decides to go and have a look at the site proposed for the French factory, acres of unspoiled English fields which the environmentalists, surely, will not give up easily. It will be a protracted and costly battle. But, with so many people looking for jobs, the bankers and industrialists will certainly prevail in the end. Traditional England will be swallowed up by the inexorable purveyors of modern commerce.

“You know “, says Old Tom when they’re back in the car, “it’s a funny feeling selling land to foreigners so near the White Cliffs of Dover. A thousand years of defying anyone to take them and now they can have them for a few miserable euro dollars”.

Telford is not going to take this lying down. Here he gives the rebuttal which the pro-EC campaigners delivered in the 1975 referendum and the Remainers are still repeating today.

“That thousand years of defiance, as you call it, has caused a lot of graveyards. Those White Cliffs are echoed in tombstones all over the world. If we can only find a way to work with other countries, in other countries, we’ll all be so interdependent that wars are impossible. And, my God, that’s worth more than all your piddling ideas about Great Britain. Or Little England, if it comes to that”.

“I was beginning to wonder how far to the right I had to go to get a rise out of you.”

A line that might have been written yesterday; Tom had only been trolling.

Predictably, Telford finds a way to bring home the deal with a clever solution which will please everybody, including the environmentalists, and also cut the cost of the project by a whopping million pounds. The price, however, is that he is late for dinner and incurs the wrath—or rather, since these are English people, the chilly disapprobation—of his wife. In his exhaustion, he gets into a fierce argument with his brother-in-law the bolshie doctor about the greed and pointlessness of bankers vs. the underfunding of the National Health Service.

“Bankers”, says Simon the brother-in-law, “they don’t produce anything tangible, they just move around all the cowrie shells keeping back one in every ten for themselves.”

On another familiar note, he’s pissed that the bankers do themselves so proud on the wining and dining front when the money they suck out of the system might be spent on something more worthwhile, like healthcare.

“If I have a consultation with a colleague I don’t expect the hospital to pay for a twenty quid [sic. hoho!] lunch while we talk, it’s two different sets of standards”.

Telford defends banking as a necessary, indeed a crucial, means of channeling savings into making a productive future, not to mention paying taxes to fund the NHS.

“Without a banking system it would be very hard to produce anything.”

But you can see in the end that he lacks conviction. He is the embodiment of an ambivalence which carries through to the Britain of today. On the one hand he is nostalgic for a time when things seemed simpler and more solid, to the days of Old Tom when he felt “safe, somehow… secure”—a time before Britain’s entry, following a referendum, into the EC. And on the other, he sees the financial and moral benefits of belonging to a greater community.

What is most striking about this dinner is not that the arguments haven’t changed in forty years. If there’s one thing most Britons will probably always agree on it is the poor state of the NHS and the railways, and the noxiousness of bankers. What has changed is that the bankers have since outdistanced the doctors (and everyone else) by an extraordinarily wide margin. One in ten cowrie shells looks quite a miserly take nowadays. Today’s international financier lives in a mansion and wouldn’t be seen dead in Telford’s rather modest little abode. And while Mrs Telford is something of a figure in London’s social life, chez Telford she still does the cooking and puts the dirty plates in the dishwasher. Unlike his modern counterpart, Telford flies coach or even goes by ferry. Doctors, in the meantime, still struggle trying to keep the NHS afloat and are now so far below the executive suite in the pay leagues that seem barely to live in the same country. Many doctors, apparently, even before the Brexit referendum, were giving up the struggle and moving to Australia where they can make a better living.

This raises perhaps the most puzzling aspect of the whole fiasco. The Tory party has always been the party of the bankers and industrialists. It seems clear that membership in the EU has been unequivocally good for business and, especially, for the City. Leaving the EU will very likely be a disaster for the London bankers and for commerce as a whole. And yet the whole mess was brought about by this party of the bankers, or at least by its chronically Eurosceptic right wing: it was to shut them up once and for all that David Cameron called for the Brexit referendum (which he thought the Remainers would easily win) in the first place. Whence this suicidal impulse from the party of the rich?

Nobody knew, at the time Telford’s Change was being written and filmed, that Margaret Thatcher was just around the corner, making Old Tom look like Aneurin Bevan, nor that 40 years later the Little Englanders would have overturned the entire applecart. Nobody knew, either, that, under the ruthless rule of Thatcher-Reaganomics, one million unemployed would in a few years come to seem like the good old days. Well might the modern average Briton ask: “What has the EU ever done for us?”

Perhaps that is the nub. Perhaps with the logic of post hoc ergo propter hoc the Tory Brexiteers are parading a giant exercise in denial. Admit the cataclysm that the “free market” has created and just… blame it on Brussels. While Telford’s Change highlights the issues with extraordinary prescience, Telford himself might well be baffled by the way it turned out.