Slogans are an integral part of Chinese politics, and a constant of daily life in modern China. Red banners bearing slogans hang from highway overpasses and line the railways along sidewalks, the banners’ deep apple red a prominent color in Beijing’s urban palette.

But the messages they bear, in white characters two feet tall, are likely ignored by the majority of the city’s 22 million inhabitants. They are busy going about their own lives in an already ad-saturated environment. Commercials are increasingly aggressive—they appear even on bathroom mirrors and in residential elevators. Flyers paper the walls in office building stairwells. Shops that open up to the street hang handheld megaphones that play pre-recorded phrases at blaring volumes: “Good news! Big discounts! Good news!” While some sectors may still be beholden to a planned economy, capitalism is thriving in Beijing. Keeping tabs on the latest political slogan is not top of mind.

That doesn’t stop the propagandists from trying, though. As of late, the most pervasive slogan is “别忘初心”. This phrase, which is most often rendered in English as ‘never forget why we started’, has its origins in a poem from the Warring States Period (475-221 BC). Similar to how Mao Zedong would repurpose phrases from classical literature, poetry, and songs, Xi Jinping has given this ancient slogan new uses.

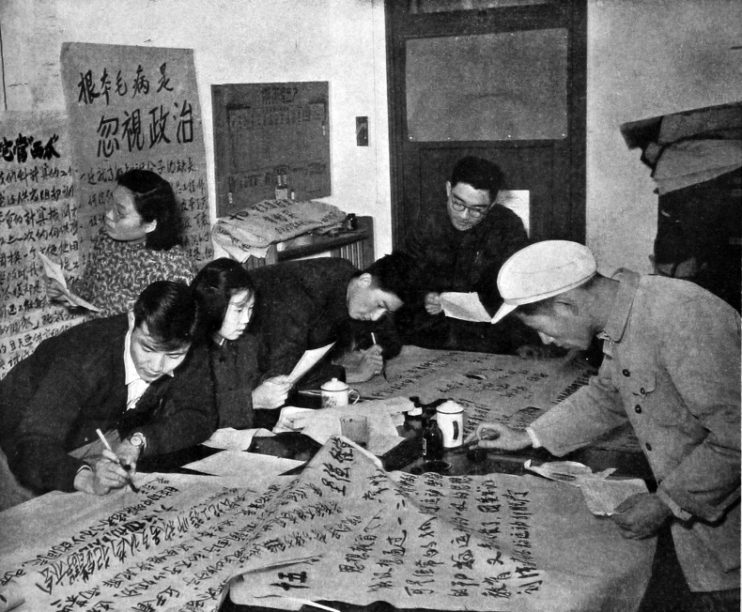

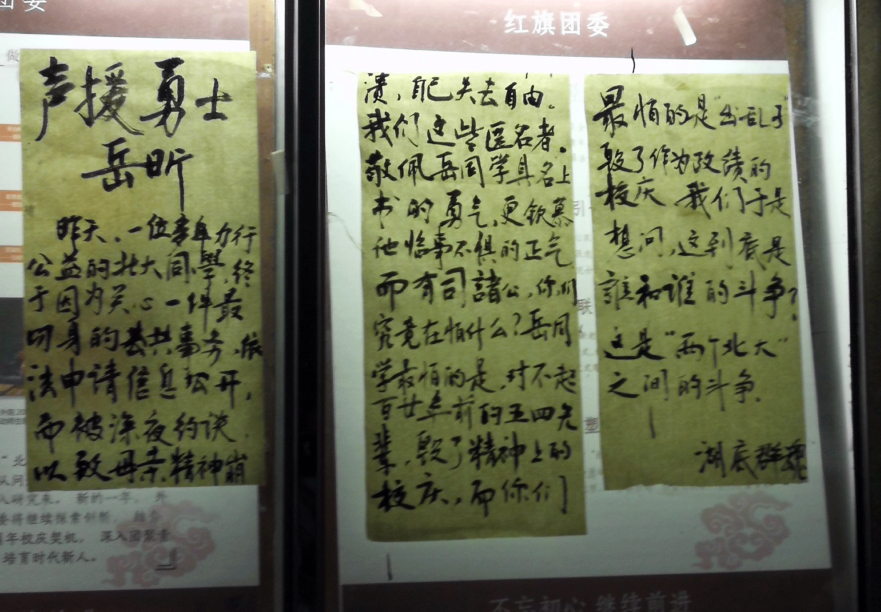

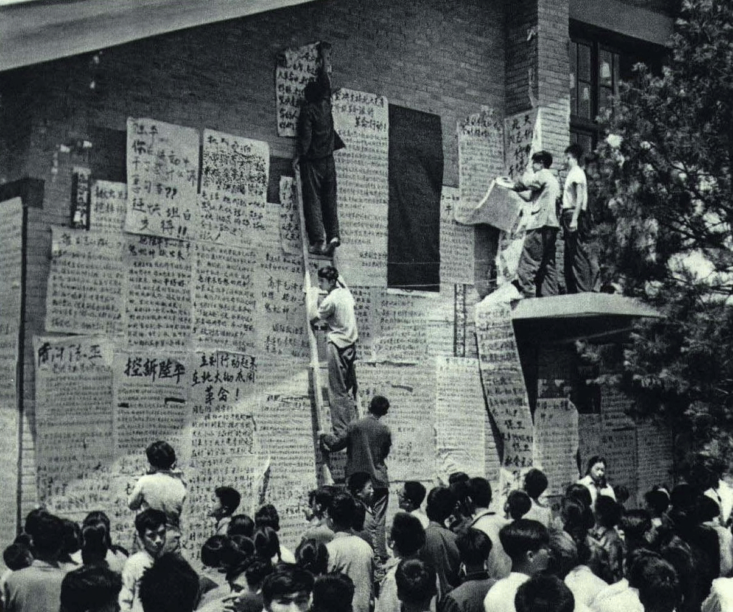

During the years under Chairman Mao, as a new nation was coming into form, slogans were often direct calls to action. Large swaths of paper with thick hand-painted characters would be pasted throughout the city, hung in public places. Sometimes the slogans could be devious in their design. For example, to show a willingness to hear criticism of the communist party, Mao opened the conversation with “let a hundred flowers bloom; let a hundred schools of thought contend” 百花齐放 (1956). But when people produced strong denunciations of the CCP, they were punished. (There’s still no definitive analysis as to whether the campaign was a genuine one that soured, or a ploy to get “counter-revolutionaries” to reveal themselves.)

public domain via Wikimedia Commons

public domain via Wikimedia CommonsLater Mao extorted peasants to join collective farms with the slogan: “Dare to think, dare to act” 敢想敢干 (1958). This policy eventually proved disastrous, resulting in widespread famine and death. Then, during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) there were slogans that were either meant as incitements to violence, or were interpreted as such. There was “smash the four olds” 破四旧 (1966) and “to rebel is justified,” 造反有理 both of which led to loss of cultural artifacts. As of yet, there has been no official account of the damage done, eyewitnesses recall the destruction of classical literature, paintings, architecture, and other works of art.

Post-Mao, when Deng Xiaoping became the de facto leader of a young country, his slogans were less like calls to action and more like notifications—indications of a changing China. He set China on a new path of economic development and greater international connectivity when he announced the policy of “reform and opening up” 改革开放 (1978). In direct reversal of “the collective” and “the dictatorship of the proletariat” there was a new concept swirling around: “wealth is glorious” 致富光荣. Previously there had been an emphasis on “correct thought,” but Deng took a different view: “it doesn’t matter if a cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice” 黑猫白猫能抓耗子都是好猫.

Deng was straddling a difficult divide; by bringing in free market capitalism, so vilified under previous leadership, the CCP faced an existential crisis. After all, how can one be politically communist whilst embracing a market economy? Ever a statesman, Deng used clever maneuvering; naturally he had a slogan to go with his solution. He gave us a new concept: “socialism with Chinese characteristics” 中国特色社会主义.

Political slogans, read backwards, can be a kind of CliffsNotes on modern China.

Each generation of the PRC’s leadership has defined its time in office with slogans. In China, where the government rules top-down, slogans are more than pithy catch phrases—they inform the general populace of the Party’s plans, which act as the blueprint for the nation’s development.

President Xi Jinping faces unique challenges in delineating a path to achieve two goals: to ensure the continued survival of the Communist Party, and to strengthen China. Neither is straightforward. The communist party has experienced a slow-burning crisis of faith ever since Marx was swapped for the market. And with economic growth slowing, the credibility of the CCP comes into question. An unspoken pact had kept the peace between a single-party state and the billion-plus citizens it governed: if the party fostered conditions that spurred economic development, and eased the nation out of poverty, there’d be limited calls for political reform.

This impasse, in part, informs their usage of the slogan: 别忘初心 (biewang chuxin), or “never forget why we started.” Xi’s proliferation of the phrase “China dream” or “Chinese dream” 中国梦 has received more attention in the Western world. The slogan, “China/Chinese dream” has several interpretations. Some suggest that the term refers to a broadly held aspiration for national rejuvenation; a vision where the next one hundred years are “China’s century” and the PRC regains its mantle of global superiority. Others suggest that the phrase is more or less the same as “the American dream,” a national aspiration for economic mobility. The only difference is this time the dream is dreamt in China.

public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

public domain, via Wikimedia CommonsIn either case, the future-looking “Chinese dream” is directly in contrast to the past-looking 别忘初心. This slogan has been translated into English with varying iterations, including remain true to our original aspiration and remain true to the founding mission.

These renditions remind CCP cadres to stay the course of the original goal of the communist party. At the same time, exhorting party members to “remain true” to an earlier aspiration suggests that there has been a deviation from that original path.

Looking back to the early 1900’s, the nascent CCP was both a political party and a revolutionary movement. The early members, just a handful of people, were seeking an alternative method of development for China that would achieve several aims. One goal was to strengthen and industrialize a massive country that was largely poor and agrarian. The second goal was to regain the national pride that had been lost after the “century of humiliation” (1839-1949) a perceived period of national weakness that had been taken advantage of by foreign powers.

Marxist-Leninist theories held an understandable appeal for Chinese radicals. Communism promised a new kind of society, where class exploitation and oppression would disappear. With experiences of being exploited at the hands of outsiders so fresh in the collective memory, it seemed that communism would protect China from future incursions. And while Marx and Lenin may have been Westerners, they provided a stinging condemnation of Western imperialism and a lucid explanation of what had happened in China. Seeking to understand and avoid what had happened over the past century, Marx and Lenin provided a guiding light.

Thus the ‘original aspiration’ of the CCP was to regain national pride and strengthen the nation, via communism. When Xi Jinping or other leaders use this admonition 别忘初心, to ‘remain true’ to the founding impetus of the CCP, they invoke, too, a sense of national humiliation; a disgrace to China that should be rectified.

The phrase is also frequently translated as “never forget why you started.” This rendition again refers back to the formative days of the CCP, but it uses a slightly stronger tone than the first. The imperative “never” sounds like admonishment. The phrase—”never forget”—is a goading to recall that chip on the shoulder. It reads as a folksier, almost familial version of the more formally translated, “remain true.”

The ambiguity of the slogan’s resonances works in Xi’s favor; the phrase can be interpreted differently for different audiences. It can be at once both formal and familiar. It can also be read differently depending on what you think of as the “mission,” or exactly what former time is being referred to.

Never forget why we started. The slogan is malleable in other ways, too. It puts emphasis on the earliest days of communism and calls to mind the founding fathers who sought to pull the nation out of poverty, regain prominence on the international stage, and recover the “face lost” after the century of humiliation. The mission here is clear then: stay true to communism, even in its changed form.

Then, when the phrase (别忘初心) is directed at the general public, the Party paints itself as the inheritor and successor to a 5,000-year-old Chinese empire. Similar to “make America great again,” the phrase in context nurtures a sense that there is some real (or imagined) former glory that can and should be regained, and a rich history that has gone awry. It calls on people to stick with the party and fosters patriotism—again as in the USA, perhaps, a patriotism tinged with the sting of victimhood. Whether the public takes it on board or not, the subtexts of the slogan are revealing.