Reading poetry and Googling rates of decomposition, on my fourth cup of coffee, I prepared myself for the nasty task of exhumation. I didn’t want to disturb her remains, but if somebody had to dig her up, if anyone must pry her bones from the soil, it was going to be me.

I wasn’t about to let the capitalist cucks of our property management company touch my fucking tortoise.

Years ago, in Harlem and in love, my ex and I took a Russian Tortoise off the hands of a wealthy little girl on the Upper West Side. She (or more likely, her caretaker) no longer wished to take care of the animal. Along with a terrarium, wood chips, light bulbs, and other paraphernalia, we carted our new pet home in a cab. We named her Rita and we loved her.

Concurrently, my mental health was severely deteriorating, made worse by a burgeoning opiate addiction. I slowly imploded myself and the relationship. I was undeservedly awarded custody of Rita in the breakup, even though I was the one leaving. Likely, my ex knew I needed Rita more than she did: Even in my wake of destruction she was the stronger one, without need for some reptile crutch. All my New York friendships had been made in the web of our love and had been snipped, appropriately, by those who cared more for her well-being than mine, in the taking of sides; she knew deep down I was weak, and she released Rita into my care with my health in mind, not letting me crumble alone.

But I was very alone, save for Rita, and spiraling. The peak of the thermometer burst when I was 51-50’ed for a suicide attempt. After an extremely dark winter, an opportunity came to move back to Los Angeles. Rita came with me, mailed by a friend, according to the appropriate standards I’d researched on a Russian Tortoise forum.

Shortly after her cross-country expedition, she died.

Teary-eyed, I wrapped her in an old shirt and delicately placed her in a shoebox. I borrowed a shovel from the neighbor and buried her on the side of the house. Face red and wet, digging a hole in the hot summer sun, I mourned New York, the relationship, my friend.

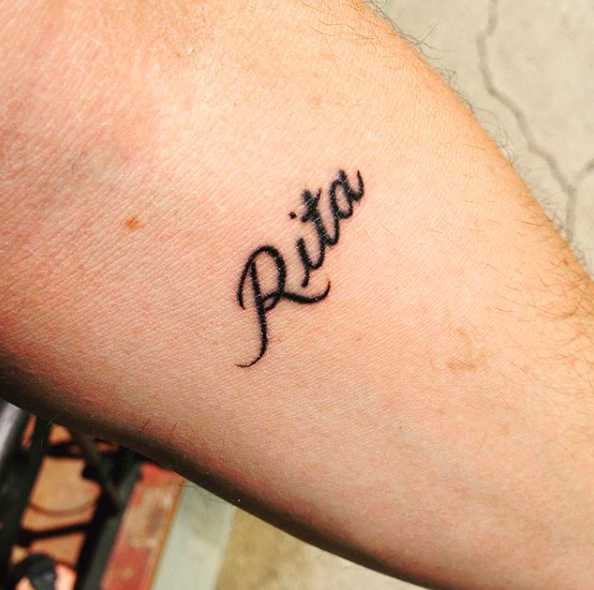

Later that day, I got her name tattooed on my left arm. Sometimes, when people learn that “Rita” was a tortoise, they ask if I’m joking. I’m not sure what the joke is, other than myself. I loved her. I loved where she came from. When she died I felt a small hole suck into me, but I like to remember good things, finding it harder all the time. It’s just one small monument, as permanent or impermanent as I plan to be.

Of course, a pet means more than itself—it is a symbol too, no? An emblem of that seminal relationship, the first person I loved as an adult, the first romantic partner I lived with, the subsequent fallout. A representation of my second life in New York, post break-up, a symbolic archive of long depressed nights lying sleepless in my shoebox Park Slope apartment, staring glassy-eyed at her terrarium while she clawed back at me, knowing, seeing, all my depression and abuse beside her comfort. And who cares if that was impossible, scientifically speaking? Who has measured the empathy of tortoises? If I felt it real, was soothed and my interior life affected, then does it matter? Absolutely not. She was my friend.

Three years after Rita died, I had moved down the street and the house where she was buried was still occupied by friends, and we assumed it would be for a long time—until the property owners decided to evict them and sell the house.

Rita had to be retrieved.

Why did I need this? I’m not sure I know, even now. I often wonder, if my mental health had improved, if the opiate usage had decreased rather than increased, if I’d existed in some healthier, drugless parallel universe, would I still have dug her up? Maybe her remains were symbolic of the light before the dark. Maybe I was just insane.

I began by Googling things like “how long does it take for animal bodies to decompose” or “standard rates of decomposition.” I found most of my information using cats as a proxy; the internet possesses far more burial knowledge of felines than it does of the noble tortoise.

I wondered if I should buy a shovel, or just hope that the neighbor was still there and home to lend it to me again. It felt absurd, suspicious even, for a single man in a second-story apartment to own one (1) shovel and… absolutely no other tools.

Luckily, the neighbor and her shovel were still there. I set to work digging Rita up, first removing the terra cotta marker I’d placed where I buried her. As I got as deep as I remembered having buried the box, I noticed a few threads of dark blue cotton, undoubtedly from the shirt I had wrapped her body in. Then I scratched her shell—all that remained. Almost the entire shirt and all of the cardboard had completely disintegrated. Same for her organs and bones. I carefully removed the shell from the grave, perfectly intact, dirt cascading from the vessel.

I cleaned the shell and drove with it to my favorite spot in Griffith Park, a quiet cedar grove with a view of downtown. I figured if I’d been buried for three years, I might enjoy some fresh air, dead or not. It may sound silly but I do silly things all the time, and often without thinking. I sat with her on a bench for a good long while, contemplating rates of decomposition. How long does it take for love to rot? For depression and Oxycontin to decay the heart and mind? For time to deteriorate pain?

A large part of hurt and guilt, at least for me, eventually requires some distance, putting it in a box and burying it for a while, thinking about it less and less, only to unearth it one day hoping all the organic tissue has magically disappeared, now just shell and bone, petrified memory and pain, still and small enough that you can turn over in your hand, reading its history without getting any shit on you.

That’s how I look back on that dark time in my life, still and skeletal, details blurring, decaying. Seeing it as a product of choices, circumstances, and environment, now fixed in place, removed, the decaying at an end, where I can examine it with some perspective.