My grandmother died during the August break in 2014. She was buried a few weeks later according to the customs of the Catholic Church, a faith she had accepted only a few months before her death. When the obituary came out, her name was written: “Madam Maria Igede Emojevu.” My grandmother, who had spent her life resisting Christianity, who had an insane knowledge of herbal medicine, whose gifted fingers loosened taut muscles and straightened bones—this woman who’d stayed faithful, well into her old age, to the gods her own mother had worshipped—was in death “Maria.”

We called her Titi. She loved her tobacco snuff and ogogoro. One of my earliest memories of Titi was of her and my mum at each other’s throats after my mum emptied her bottle of ogogoro in the gutter in front of our house in Warri. She rarely visited us, but if someone in Egbeleku, the village she lived in, was coming to Warri she would send food items—dried fish, garri, plantain, spices, cocoyams, and medicine when I started having period cramps. The most painful cramps started during my teenage years when my allergy to Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs meant I couldn’t take easily accessible painkillers. When my mum got tired of hospital trips and prayers that didn’t reduce my suffering she went to Egbeleku. There Titi made me a herbal mix of roots, spices, and dry gin that reduced the intensity of my cramps.

Perhaps she was tired of fighting with her children over her religion, or scared of the unknowingness that comes with death. So she accepted the Church and was baptized “Maria,” because a name like “Igede” would lock her out of heaven. A funeral mass was held for her in an old Catholic church a short distance from her father’s compound in Ewvriyen. The mass was offered “for the repose of the soul of our mother, grandmother, wife, sister, aunty Maria…” in our language, Okpe. I wondered how God could hear masses in Okpe but would not admit people with Okpe names into heaven.

In her obituary posters she appeared sitting on a chair, wearing a blue blouse with puffy sleeves sewn with a thick lace fabric, a large brown gele accentuating her thin face, her sharp eyes peering into the camera, unsmiling, as if she knew it would be her last photo.

Every two years, choristers from Catholic University Chaplaincies in Nigeria gather in a designated university for the Forum for the Inculturation of Liturgical Music (FILM). It is a quiet music competition with simple rules: every participating university choir must perform original liturgical music, written and composed by them in indigenous languages. Choirs are also to sing in languages other than the ones spoken locally. For example, the choir from the University of Ibadan must perform an original song in a language other than Yoruba. These songs, in Urhobo, Bini, Esan, Hausa, Fulfude, Ijaw, Idoma, Tiv, Kalabari—there are more than 200 languages in Nigeria—move from FILM to parishes and become regular songs, sung during masses.

University choirs aren’t the only groups composing liturgical music in Nigerian languages, but FILM brings a large and very diverse cohort together, so there are more songs, and they travel faster. They’ve gone on to replace the traditional Latin/English Kyrie, Gloria, Creed, Agnus Dei, Santus, Pater Noster. Even the classic Ave Maria, composed in 1825 by Franz Schubert, took a new form when the choir from Nnamdi Azikiwe University composed an Igbo version: Ave Maria, I ju puta ra na amara onye, ekele dirigi maria, nwanioma ezigbo nne.

In my third year at the University, my choir had to learn the Creed in Izzi, a language spoken by the Izzi people of Ebonyi State. It is an Igbo dialect but quite distinct from other Igbo dialects. Over weeks, we gathered under a mango tree for rehearsals. The tune was simple enough, but to pronounce the words with the correct Izzi intonation was grueling. After weeks of constant rehearsals, the words became as smooth as river pebbles on our tongues just in time for our joint mass with the indigenes of Izzi. Usually, students and indigenes worship separately, but on a few occasions we had joint masses, during which the Izzi people—many of whom couldn’t read, write or understand English—looked on numbly as we sang in Latin or English.

That Sunday was different. When we began to sing the creed: Mu kweru le Chileke bu Nna/Kweta le Chifu Nna/Bya kweta le Chileke du nso, I watched as recognition lit up their eyes and when they were certain of what we were singing, they joined in the chorus: Mu Kweru le Chifu Nna.

No choir has been as preeminent in the FILM competition as the St. Albert Choir from the University of Benin. The choir has always delivered nearly flawless renditions of original songs, blending melodies, harmonies and choreography smoothly into their performances. Their 2013 composition and delivery of The Creed in Bini titled Iyayi won them the competition that year.

It received high praises from the judges and other choristers and soon, many chaplaincies and parishes began to use that version of Iyayi for mass.

There are more than fifty Catholic parishes in Benin, and the relationship between the church and the kingdom is dynamic. The Benin Kingdom was one of the first African kingdoms to receive Catholic missionaries from Portugal as far back as the 15th century. Although diplomatic relationships developed for the sake of politics and trade, the missionaries were unable to convince Benin people entirely that the God of Israel whom they could not see was greater than their gods, than their Oba.

Converts found an eventual balance between Benin and Catholic; they became a people who received Holy Communion at mass and returned home to pay homage to their ancestors. Even today Benin City is a Catholic-Bini merger, neither completely Christian nor traditional, a thriving dilemma.

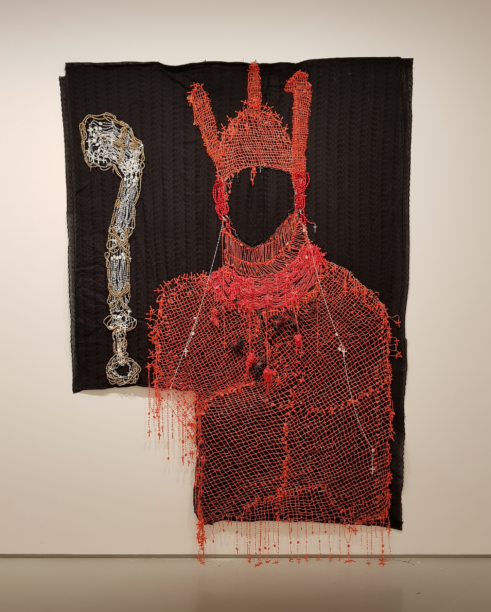

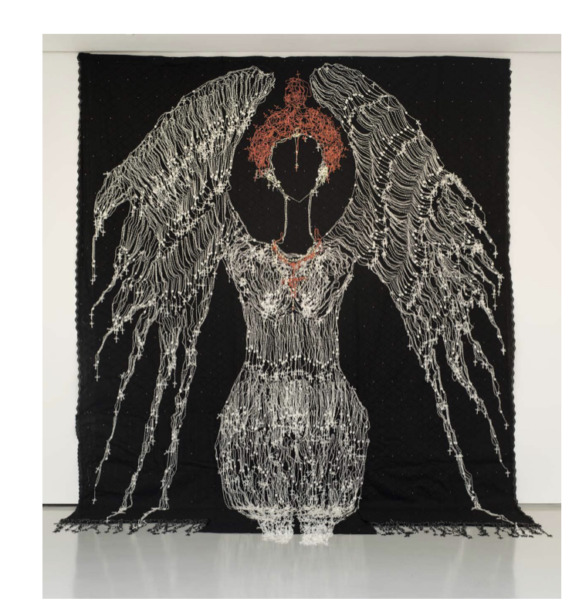

The work of Nigerian artist Victor Ehikhamenhor speaks to this hybrid culture. Consider three pieces from his recent collection, “In the kingdom of this world”: “I am Ogiso, King of Heaven”, “Queen Idia, Angel of Kings” and, the most intriguing for me, “my last dance as King before sir Harry Rawson army arrives.” These three figures are deeply embedded in Benin culture. They represent the beginning, peak and decline in power of the dynasty. By recreating them with rosaries, the most popular symbol of Catholicism, Victor affirms this dynamic relationship between Church and Kingdom.

Victor portrays these historic Benin figures with hundreds of red, black, white translucent rosaries and traditional red coral beads: Ogiso, one of the god-kings who founded a great dynasty; Queen Idia who led men to war to preserve the dynasty; and Ovonramwen a direct descendant of the first Oba, Eweka 1, who held off British imperialism before he was violently deposed and exiled for colonialism and Christianity to thrive in his kingdom. While Ogiso sat majestic on his throne with his sword, Idia glowed in the dark like a guardian angel, and Ovonramwen performed his last royal dance, standing tall, fully clothed in rosaries and coral beads before Harry Rawson arrived.

After my grandmother’s funeral, my amusement at her name being Maria morphed into curiosity. I had secretly loved her resistance to the church. What had the Catechist told her, that made her change her mind?

I was born Catholic, baptized as an infant and indoctrinated through various means, the most effective being the catechism classes where I was taught about faith, and hope, and the sacraments and commandments of the church. I felt special, and proud; I had a dedicated guardian angel and patron saint, white cherubs with curly blond hair, always willing to do my bidding.

Decades flew by and my pride was replaced with shame when I began to read about the history of the Church in Nigeria. How could the missionaries preach the love of a father who could not abide what we were unless we shed ourselves completely, and became Marias and Josephs? Why did evangelization condemn, destroy and erase our cultures through oppression, and through carrot and stick approaches?

I am a product of that aggressive evangelization. An Okpe girl, Catholic before she is other things, able to chant prayers in Latin but not one in her mother tongue.

It is intriguing to watch the gradual Nigerianization of the Church. I admire priests like Rev. Fr. Moses Iyara who wrote, “The Eucharist: Pantheon of Family Rituals” and other priests writing research papers, drawing parallels between rituals in the Church and Nigerian culture. Priests and clergy members who have translated the bible, Catholic missal, hymn and prayer books into many Nigerian languages.

It gives me a heady feeling, that after those decades of white priests celebrating masses in Latin with their backs to the congregation, our familiar home things, words, names, and imagery from within and around us are represented in the Roman Catholic Church. I am silently ecstatic that children can be baptized as Ifesinachi, Imoter, Ufuoma, Osasuyi. That God who first came to us as Jehovah, El Shaddai, Elohim, is also Oba, Oghene, Chiefu, Chukwu, Aondo; that I can now see the almighty not as an old, greying white man, but like Victor Ehikamenor’s “Ogiso,” adorned with rosaries and coral beads, our own God. Uku Akpolokpolo.