Protests often become most intense at night, when some try to make the last train because they have school or work the next day, and TV stations pack up and leave. With fewer eyes watching, the police no longer feel as much restraint. After ten weeks of demonstrations in Hong Kong, the police have become more aggressive after nightfall—though they’re perfectly happy to start firing tear gas in the afternoon, now. And it’s not just police, but sometimes attacks by pro-China gang members, as well.

So I’ve fallen into a rhythm of staying up watching livestreams, starting to write at around 4 a.m., and trying to get a piece out by 6 or 7 a.m. Then I get breakfast/dinner and sleep until mid-afternoon, or until whenever the hot Taiwanese summer wakes me.

I got my piece out by 6 a.m., and, struck by sudden inspiration, started writing another, comparing Hong Kong and Taiwanese political elites. As I worked, with too much pent-up anger and adrenaline from watching all these live streams, I started getting into flame wars online.

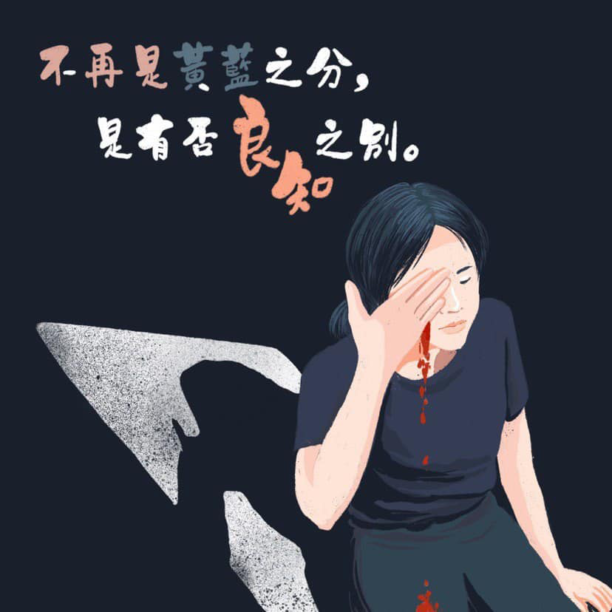

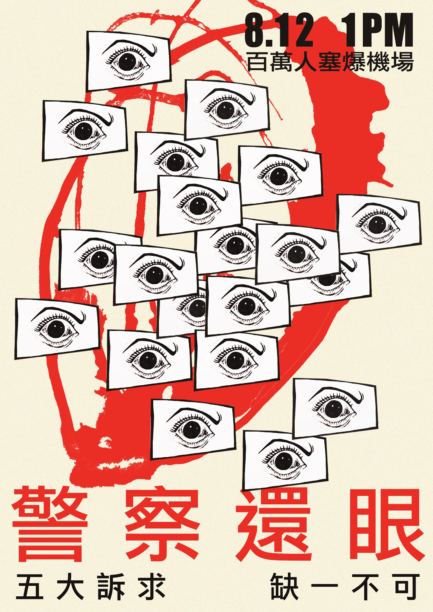

Sunday night saw possibly the highest level of police violence to date. Police shot out the eye of a female medic with a bean bag, fracturing the bones in her face. Another widely circulated video shows police pushing a male protestor’s face into the ground with enough force that he screams that they are breaking his teeth. Tear gas was fired in an underground MTR station with no ventilation, with the tear gas canisters fired directly at demonstrators.

At around 2 a.m. a demonstration had been called for the following afternoon, to occupy Hong Kong International Airport and disrupt its operations entirely. I was astonished by the vast amount of art produced in just a few hours to spread word of the demo, much of which was eye-themed. But some western academic thought the airport action would turn into a riot involving clashes with the police, and began flipping out online in response to my report.

He said he was at the airport, and appeared to be upset about the disruption of his schedule, and the waste of the tickets he’d bought months ahead of time. He claimed to be worried about what would happen to him and his family if there were violent clashes. His remarks seemed extremely tone-deaf to me. He had around…eight hours to get away from the airport, I thought.

There are elderly residents of Hong Kong who’ve taken to wearing gas masks at home because their neighborhoods have been so frequently tear-gassed by police; they don’t have the luxury of escape. Ridiculously, this man claimed that the biggest flaw of the movement was its lack of electoral aims. Hong Kong’s electoral system has long been compromised, with candidates routinely blocked for running for office, or disqualified after taking office.

Next, a friend subtitled and posted the video of the male protester whose teeth were being shattered by the police. It was quickly taken down due to a copyright notice from the originating media outlet. The editor-in-chief of this outlet was apparently protesting the loss of hits and “virality,” whatever the hell that means. Despite having been credited in my friend’s work, this editor preferred to see the subtitled version deleted.

Osamu Dazai once said that journalists are like terrorists, the suggestion being that journalists profit from bloodshed. This editor seemed me to be exploiting the previous night’s suffering; I was reminded that the same editor had run an outlet that staked out territory covering Hong Kong in the English language in the wake of the 2014 Umbrella Movement.

I’m a journalist too. I also need to eat. But I cannot understand in what context I would ever prefer, say, that a translation of my work, posted on a website not run by myself, cease to exist on the internet, period, rather than retain exclusive control for those sweet, sweet hits.

Lastly, I got into a flame war with a bunch of Taiwanese Donald Trump supporters on a political meme fan page on Facebook who were evidently unaware of the fact that Trump had claimed protests in Hong Kong were a “riot”, that he viewed this as an internal matter, and that he had faith in Xi Jinping to take care of things.

Well, I tend to suffer from Internet rage issues. I finished my piece, wrapped up my flame wars, ate breakfast and slept at around 11 a.m., setting my alarm to wake up at 1 PM for the airport protest two hours later.

I awoke to learn that Handy Chiu, the chair of the Taiwanese New Power Party (NPP)—and perhaps the politician with the worst English name in all of Taiwan—had resigned in a press conference.

The NPP was one of the third parties in Taiwan formed after the Sunflower Movement; many of my fellow activist friends were part of it. The party has experienced an internal crisis in the past few weeks, rocked by scandals and seeing the departure of key figures, such as heavy metal star turned politician Freddy Lim.

Not exactly what I’d expected to wake up to. I dashed off a piece and got it out by 3 PM, while simultaneously keeping a live stream of the airport protest open, then edited a friend’s piece on the resignation.

Never put all your eggs in one basket, I thought. As the years went by, I knew I would eventually discover some of my old friends to be inept politicians, or even see them grow as corrupt as the opposition we’d fought to supplant. I can’t even rule out the possibility that eventually I’ll become someone not exactly myself, as time goes by. That’s the nature of power.

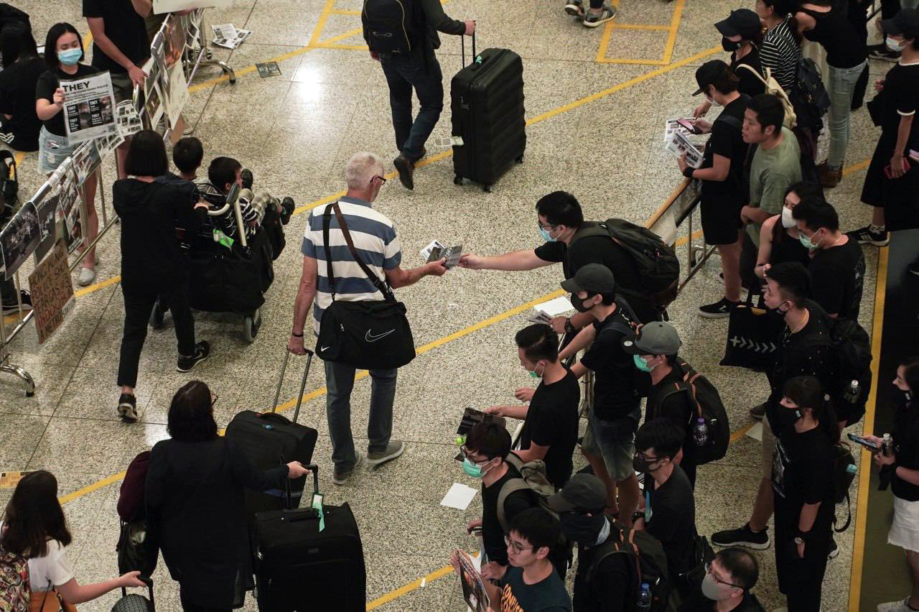

Then it was time to focus on the airport protest.

I had two chatrooms open during this time, one of a Hong Kong left group I had become involved in, and the second the internal chatroom of New Bloom, the Taiwanese left publication I founded with a bunch of other then-student activists after the 2014 Sunflower Movement,. Reading the messages in the Hong Kong chatroom was weirdly calming, while the Taiwanese chatroom was incredibly anxiety-inducing.

I am not sure why. I would have expected the opposite.

Everyone in the New Bloom chatroom seemed to have a friend or knew someone who happened to be in the airport at the time or was panicking about the possibility of military intervention. I guess that says how much air traffic passes through Hong Kong International Airport. Or how interconnected the world is nowadays. Some of us tried getting our friends to pair up, for safety in numbers.

All the flights for the day were canceled. Then the rumors started floating around. That the lights, Wi-fi, and electricity in the airport had been cut. That tear gas warnings had been issued. That the Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office, which was holding its third press conference on the protests at the same time as the demonstration, had declared this to be “first signs of terrorism,” possibly as a pretext for an imminent crackdown. Videos began circulating online of inbound military vehicles.

I’ve had a half-baked notion of flying back if the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) were ever to intervene. I know my being there really wouldn’t change anything. But, emotionally, I feel some kind of obligation to bear witness to history, no matter what the risks are. I thought, that’s the least I owed to my Hongkonger friends.

But now I realized that, as the skies over Hong Kong on flight radars began to look terrifyingly empty—with all flights to Hong Kong redirected, or turning back to their points of origin—that if this if this ever came to pass, I would likely end up being shut out in Taiwan. And if it ever came to that point, God forbid, who knows if I would actually have the nerve to make that leap.

Watching all these livestreams, chatting with a Hong Kong journalist based in Taiwan, I realized how little of the stream content I getting apart from the images, given my total lack of Cantonese ability. There was one with a male reporter wandering around the inside of the airport; another with a reporter wandering outside. A third, which I could understand because it was in Mandarin, was of a reporter discussing English-language protest signs for the benefit of those who couldn’t understand English.

I can usually understand most of the Cantonese press conferences held by the Hong Kong government by watching the live comments section. All the angry responses in the comments usually provide a pretty good live translation of whatever government officials are saying. But all the livestream comments here were just things like, “Add oil!” (加油), a term of encouragement, “Be careful!”, “Thank you journalists!”

In the end there was no crackdown. They were all just rumors. The lights, electricity, and Wi-fi weren’t cut. Videos of military vehicles inbound had been released by Chinese state-run media outlets, supposedly for drilling in neighboring Shenzhen, but they weren’t necessarily signs of an imminent crackdown. Most demonstrators left peacefully, following the ethos of the protests to withdraw at the first sign of police responses, as a way to keep a step ahead of police actions. Tear gas wasn’t fired in the airport, nor were riot police deployed.

One can’t be certain that the situation for future protests planned in the airport will resolve so peacefully, though. With plans for continued protests in the airport, flights were canceled for a second day. Rumors continue to swirl of a possible military intervention.

Uncertainty is terrifying, let me tell you that. Nothing happened and I’m really quite glad that nothing happened. At the same time, risks are necessary. One isn’t going to get anywhere without taking risks.

At around 8 PM, I talked over Skype with a friend in Taiwan who had had a breakdown during the airport occupation. Like me, he had felt that he should immediately go to Hong Kong during the events of the afternoon. I told him how I’d realized that if it had ever came to a PLA intervention, unless we acted extremely fast and decisively, we would both be stranded in Taiwan after flights were cut off to Hong Kong. And, of course, it could be a one-way trip, frankly.

He asked me what kept me going, despite that I’m pretty open about feeling negative all the time. I’m not really sure there’s anything rational to it, just the conviction that some things in the world are wrong. Or maybe the conviction that this world itself is wrong. Honestly speaking, these manic days of high adrenaline and working in a state of complete exhaustion are the only times I feel alive sometimes—maybe because they’re the only times that I have a sense of complete certainty that the things I do are meaningful, that the life I lead is meaningful.