Apple’s presentation on September 10th gave rise to nostalgia for the vision of Steve Jobs, the company’s late founder, who was known to be very keen on “taste.” Jobs once discussed his notions of taste in 1995 in a diatribe against Microsoft, which he said “has absolutely no taste,” adding that “they don’t think of original ideas, and they don’t bring much culture into their product.” Great products, he said, were a “triumph of taste.”

Jobs’s exquisite taste was for many years a matter of doctrine in the tech world. Kevin Kelly’s remarks after his death expressed the general sentiment: “Steve Jobs was a CEO of beauty. In his interviews and especially in private, Jobs often spoke about Art. Taste. Soul. Life. And he sincerely meant it, as evidenced by the tasteful, soulful products he created over 30 years.”

The widespread admiration for Apple’s design ethos during Jobs’s tenure was in two parts: one functional, the other aesthetic. The functional aspects of Apple’s products in the era of Jobs were considered magical and thrilling. But the vibe of Apple’s product design is uniformly cool and impersonal, and the monolithic sterility of their glassy retail palaces is really something shocking. So far as design goes, it’s always been an imperial aesthetic, entirely lacking a human dimension — or a potted plant. And this was so no matter how much the marketers tried to soften things up with the aid of Justin Long, John Hodgman and sassy dancing silhouettes.

Bow down, Apple seemed to say. And in the cold, Big Brotherly sway of uniformity that it held, and still holds, over millions upon millions of people, Apple seems to deny or even thwart the natural world, and with it the individual, the mutable, the unscientific, the instinctive, the flesh and blood. It won’t surprise me a bit when they provide snow-white Matrix plugs to poke tidily into the back of your head. Or maybe even the heart plugs from Dune.

For someone who thought that taste was connected to originality, one can’t help noting that Jobs’s taste was pedestrian and derivative in the extreme; he attempted a mid-century minimalism lifted directly from Dieter Rams, for many decades the chief designer at Braun. (Rams’s influence came to Apple largely through its own chief designer, Jonathan Ive, who has acknowledged the debt.) It’s not clear that taste borrowed at two removes can be characterized as exquisite, let alone visionary. And Rams, like Raymond Loewy, that other titan of mid-century industrial design, displayed such absolute originality that it’s clear the efforts of Apple never quite reached the bar they set.

Still more strikingly, there is a huge disconnect between the ethos of Rams and that of Jobs — and Apple. Rams is an instinctive meliorist who believes that design can influence the world in a positive way: that is to say morally, not only aesthetically.

[T]he years around the end of the 50s, beginning of the 60s — there was a movement at this time to make things in another way, yes? To forget the war and all these terrible things — so, especially in Germany, we had to build cities in another way, so it was a movement to make things better and today we have lost this movement to make things better. And I am a little bit [shrugs] about our behaviour and our thinking about the future. And the future is in danger. If we don’t find new ways, new structures for education to start with, then I’m not sure if in 20 or 50 years we still can say that this planet is our home.

Rams was a hands-on craftsman, a carpenter and an architect, a trained landscape designer. He has always styled himself a team player rather than a visionary or “genius”, and yet he really did originate in large part what became the mid-to-late 20th century’s house style of product design. His work is pared-down, but rarely feels inhuman. There are knobs, for example, places where real hands might go. A shot of saturated, organic color, a plane of warm blond wood. In 2011’s As Little Design As Possible, he said, “Indifference towards people and the reality in which they live is actually the one and only cardinal sin in design.”

Rams is also a very gentle man, a pacifist who, when asked to respond to the Proust Questionnaire for designboom in 2000 had no response for many of the questions, saying memorably, “I don’t like heroes.”

This irresistibly calls to mind Apple’s absurd appropriation of the images of Einstein, Jim Henson, Dylan, Gandhi, John Lennon et al. in order to flog their wares, another indication of the stark contrast between Jobs’s approach and that of Rams. “Think Different”, those Apple ads demanded in 1997, but what they really meant was that everyone think, or at least buy, the Same. “It’s not the consumers’ job to know what they want,” Jobs once said, and this boggling remark went completely unchallenged by the hagiographizing press, no, it was widely praised. But wait — weren’t the little people supposed to be Thinking Different?!

This contrast between Rams and Jobs is symbolic of a long struggle in the West, like a pendulum that swings back and forth between the imperatives of art and commerce: The characteristically utopian tendencies of craftsmen, supplanted by a freshly depersonalized vision of a world full of “geniuses” and plutocrats, and of the underlings who are there to consume their “genius” on command. (In response to the Proust question “the reformation I appreciate the most,” Rams responded, “the one which would make the world a better place to live in for everyone.”)

Characteristically, Rams never minded a bit about Apple’s biting his style.

Some colleagues of mine, for example Philippe Starck, I met him in a furniture showroom in Los Angeles, and he said, “What do you think about Apple, the iPod? It’s a copy of your work!” I never feel that it’s a copy, it’s a compliment. Jonathan Ive sent me one of his products and I think it’s so similar to what I tried in the beginning with the brothers Braun what he now is doing with Steve Jobs — it must be a wonderful combination. Without this combination, we as designers… we cannot do it alone, we need entrepreneurs, working together with good engineers.

Steve Jobs was not a cultivated man in the ordinary sense of the word; in describing his favorite reading Jobs’s biographer was reduced to padding out the meager list with diet books:

The books and authors important to Jobs include Clayton Christensen’s The Innovator’s Dilemma which apparently “deeply influenced” Jobs, Shakespeare’s King Lear, Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, Dylan Thomas’ poetry, and the following self-help books: Shunryu Suzuki’s Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, Chogyam Trungpa’s Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism and Paramahansa Yogananda’s Autobiography of a Yogi (the only book on Jobs’s iPad 2) [!!!!], as well as Be Here Now by Baba Ram Dass, which sparked Steve Jobs to try LSD for the first time.

He also enjoyed dieting books, including Diet for a Small Planet by Frances Moore Lappe and Arnold Ehret’s Mucusless Diet Healing System.

His favorite musicians were Dylan and the Beatles.

Jobs likened The Beatles’ creative process to Apple’s own. While listening to a bootleg CD from one of the band’s recording sessions, Jobs remarked, “They did a bundle of work between each of these recordings. They kept sending it back to make it closer to perfect … The way we build stuff at Apple is often this way.”

He also framed his motivations and the principles that drove him forward in terms of Dylan and The Beatles.

“They kept evolving, moving, refining their art,” Jobs said of the artists. “That’s what I’ve always tried to do — keep moving. Otherwise, as Dylan says, if you’re not busy being born, you’re busy dying.”

(None of this is to knock Dylan or Mucusless Diet Healing, but just to observe that what drove Jobs was clearly not a personal obsession with the products of art or culture.)

Noticeably, Jobs affiliated himself with no charitable cause, made no public attempt to harness his power in the service of solving even one social or political problem. In public, at least, the disadvantaged did not interest him. In the Times in 2011, Andrew Ross Sorkin recounted conversations on this subject with Jobs’s associates: “Two of his close friends, both of whom declined to be quoted by name, told me that Mr. Jobs had said to them in recent years, as his wealth ballooned, that he could do more good focusing his energy on continuing to expand Apple than on philanthropy, especially since his illness. ‘He has been focused on two things — building the team at Apple and his family,’ another friend said. ‘That’s his legacy. Everything else is a distraction.’” (Jobs’s fortune was estimated by Forbes to be well in excess of eight thousand million dollars.) This behavior was of a piece with Jobs’s permanent elimination of Apple’s corporate philanthropy programs in 1997. There was one tiny (RED) project, a limited-edition Nano in 2006, and that was it, for the company with the biggest market cap in the US.

Steve Jobs was, in short, too much a plutocrat and too little an artist or craftsman to produce an ultimately satisfying appropriation of the warmer, more humane minimalism of the mid-20th century, which had been rooted in a vision of a more egalitarian and fairer world. To what degree do “good design,” or “taste,” depend on human values?

“The greatest foe to art is luxury, art cannot live in its atmosphere.”

— William Morris, The Beauty of Life

The connections between aesthetics, work, craftsmanship and politics have been evident from the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution. If we look to England, perhaps the first place in the modern world to suffer the terrible downside of capitalism, immediately we find John Ruskin yipping about the debasement of the working man’s character owing to the rise of the Machines, and lamenting the loss of beauty in the daily life of ordinary people and the ruin of the land. Ruskin thought that a restoration of art, of taste and craftsmanship, could rescue England from the ravages of industrialism.

Unfortunately Ruskin was plumb loco, as well as being a great art historian and social theorist. (Tthough it turns out that he never did burn those erotic drawings of Turner’s, as had been supposed for more than a hundred years. He’d just hidden them, is all.) Ruskin was a hidebound conservative who approached every question, whether of art or of social justice, from an unabashedly elitist, Christian moralistic perspective that is difficult to square with modern ideas.

His disciple William Morris, a secularist, polymath and expert craftsman of nearly incredible gifts, was another kettle of fish entirely.

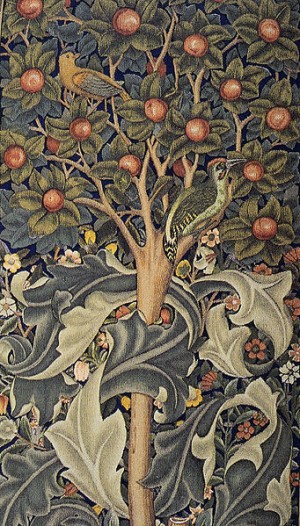

Morris is possibly best remembered as one of the founders of England’s Arts and Crafts movement, a principal figure of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, and as founder of the Kelmscott Press. He also designed and produced textiles, wallpapers and tapestries; he was a painter, a medievalist, a poet and novelist, a co-founder of the still-extant Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, and an early and dedicated Socialist and political activist. His novels gave a certain medieval flavor to the nascent genre of fantasy fiction that it still retains, even today; both Tolkien and C.S. Lewis claimed him as an influence. He also managed to translate stuff from Icelandic, somewhere in all that, and to conduct a really terrifying-sounding marriage and love life.

These capsule-biographical details don’t begin to cover what Morris was really up to, though, because he was working toward a single goal, resting on a single set of principles. He sought nothing less than the reform of English society: to reclaim his country from the soul-crushing depredations of the industrial age. He wanted to restore beauty (particularly, the making of beautiful things), human values and a love of nature to the life and surroundings of the English people. He thought that a return to making and enjoying beautiful things would right social wrongs, would equalize people and ennoble them.

There has been a tendency to trivialize Morris, to call him naively utopian, to suppose that he wanted to turn everybody in England into tapestry-weaving, flowing-haired hobbits or whatever. He and the rest of the English aesthetes are all too easy to mock, as Gilbert and Sullivan did so charmingly in Patience, and as the Italian Futurist Filippo Marinetti did in a blind fury in his “Futurist Speech to the English,” delivered at the Lyceum Club in London in 1910.

When will you disembarrass yourself of the lymphatic ideology of that deplorable Ruskin… With his morbid nostalgia for Homeric cheeses and legendary wool-gatherers, with his hatred for the machine, steam and electricity, that maniac of antique simplicity is a like a man who, having reached full physical maturity, still wants to sleep in his cradle and feed himself at the breast of his decrepit old nurse in order to recover his thoughtless infancy.

Here is the big disconnect of the industrialized world, then and now. On the one side we have the futurists, clamoring for faster, better machines, for progress, capitalism, competition and the creation of wealth. On the other, William Morris, who quoted Ruskin in his lecture “The Beauty of Life” in 1880: “Art made by the people and for the people as a joy to the maker and the user.” What faint, clumsy little echo of this message can be heard, or seen, rather, in the hand-knitted iPad covers on Etsy!

Morris mastered the techniques of manufacture personally, as a political act. He learned to weave tapestries, to make carpets and wallpapers, inventing new designs for these techniques that are still in use today. The Kelmscott Chaucer is widely reckoned to be one of the most beautiful books ever produced. Note that Morris wasn’t anti-machine, per se, but he wanted machines to free people, not enslave them. He thought that making things can empower each of us, give us a sense of agency and meaning.

In his (really good) book Dreams of an English Eden, Jeffrey L. Spear might be speaking of our own times as he delineates the problems Morris faced in realizing this vision. “The function of the machine should be to free the workman from drudgery, not to displace him nor to reduce skilled to unskilled labor, an aspect of mechanization Morris attributed to the competitive need to make the cheapest possible product.”

The urgency of these difficulties in the 19th century was nothing compared to what it is now, when industrialization is threatening the stability not only of societies, governments and institutions, but of the planet’s capacity to sustain life. Add to this the possibility of using technology to improve the lot of ordinary people, and despite all the “forsooths” and “verilys” with which Morris’s work is liberally peppered, he acquires the visionary quality lacking from Steve Jobs, or from any of our own most prominent industrialists, innovators or titans of “design.” Considered from this perspective Jobs, Elon Musk, Page and Brin, Jeff Bezos, et al., show up in their true colors: as profiteers, charlatans with little imagination or intelligence, and still less humanity.

It says something very scary about our own times, that it is almost impossible to think of any great designer, artist, politician or industrial potentate who would dare to make concrete proposals for improving the lives of ordinary people, let alone imagine how to create an earthly paradise, as Morris did in his News from Nowhere (1890). It is blisteringly obvious that the present age, in which influential patrons of the arts are to be found at a banquet wearing white hospital coats and quarrelling over vagina-shaped bits of cake, is deficient in this area.

The aim of Morris and his associates, people so original, energetic and imaginative, was to create as much beauty as they could for as many people as they could. To fill their whole nation and people with beauty; to show that everyone craves and deserves and can himself be a maker of beauty, and a participant in culture; that everyone has some stake in maintaining a commons rich in beauty, in art, music and literature. From such guys comes the idea that beauty, the operation of taste, can elevate humanity.

In a scathing 1992 New York Review of Books essay, “ Art, Morals, and Politics,” Robert Hughes disparaged the idea that art, or taste, can ennoble:

Nobody has ever denied that Sigismondo Malatesta, the Lord of Rimini, had excellent taste. He hired the most refined of quattrocentro architects, Leon Battista Alerti, to design a memorial temple to his wife, and then got the sculptor Agostino di Duccio to decorate it, and retained Piero della Francesca to paint it. Yet Sigismondo was a man of such callousness and rapacity that he was known in his life as Il Lupo, the Wolf, and so execrated after his death that the Catholic church made him (for a time) the only man apart from Judas Iscariot officially listed as being in Hell — a distinction he earned by trussing up a papal emissary, the fifteen-year-old Bishop of Fano, in his own rochet and publicly sodomizing him before his applauding army in the main square of Rimini.

Hughes is quite right. The difference between William Morris and Sigismondo di Malatesta (or Steve Jobs) is that Morris wanted to share the making and appreciation of beautiful things. He wasn’t looking to impose his own taste on the little people; instead he wanted everyone to share in the appreciation of beauty, and to create their own responses. Taste by itself doesn’t ennoble anyone, but sharing it does.

Aesthetic values are inescapably interwoven with the political values of a period. When machine-age, Futurist or Constructivist or Space-Age aesthetics have taken the reins, you’re looking at a period dominated by moneyed interests; one side of the pendulum swing. Progress, in the form of machines. Then people get to longing for a little chaos, dirt, a flower or two. This happened in the 1980s, for example, a time of truly frantic wealth-worship, the Reagan years, when Republicans began to succeed in their efforts to dismantle the New Deal. This too was a quite chilly era, designwise; the years of Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo, the black-and-white world of Calvin Klein. It was a revival of machine-age Italian futurism; hard surfaces, stainless steel, sharp corners; everything black, grey or white, with the occasional shot of red or some other unnaturally concentrated, acidic color. (Quite a lot of the one percent, meanwhile, were lounging around in plushy chintz-stuffed apartments decorated by the likes of Sister Parish.)

The horrors of Memphis furniture alone might have been a big reason for the relief felt by millions at the sight of the hopelessly scruffy, howling Kurt Cobain. Too much machine makes us miserable. His plaid flannelly uncombed unshaven genius was a welcome reminder that we aren’t machines.

The same strain of exasperation can be heard in the yodelings of the many Apple haters among us. Maybe what they really dislike isn’t just consumerist conformity or the inexorability of technological “progress.” Maybe what they dislike most is being made to serve The Machines. Wouldn’t it be nice if there were a telephone that wasn’t also a surveillance device?

These days, instead of Cobain we have got the young people of Oakland and Bushwick working toward solidarity and sustainability, and punching a few fascists. Painters, writers and musicians looking to make a decent living at their art, rather than to get rich. People who want to grow their own food, or crochet their own bedspreads. To use less and have less, but to have more beautiful things, and more mindfully. There are craftsmen trying to bring things back to a more human, manageable scale.

William Morris was celebrated in his lifetime, but he suffered a profound political disillusionment, as visionaries and revolutionaries often do. Even so, his vision really kind of succeeded, because Morris’s influence is in part responsible for the fact that there are so many unspoiled places left in England, so many unbutchered buildings and carefully preserved works of art. The Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings has got a website now; I wonder what he would make of that. He influenced countless collectors and patrons, curators and policymakers (to say nothing of Prince Charles. Oy.). But for the influence of Morris, England might be as carpeted in mini-malls as Los Angeles is. Being the visionary he was, Morris dimly foresaw this turn of events.

I pondered all these things, and how men fight and lose the battle, and the thing that they fought for comes about in spite of their defeat, and when it comes turns out not to be what they meant, and other men have to fight for what they meant under another name.

—William Morris, A Dream of John Ball

Editor’s note: a version of this essay appeared at The Awl in November 2011.