When I was studying at Oxford, I spent one week at the close of Hilary term in London with my friend Rosa and her family. Mostly we wandered about and went out with friends, but during the day, we worked at the British Library on Euston Road. I do not remember why we decided to spend the first days of a holiday there, but we did, and so one morning we took the train from Dulwich up to King’s Cross and found the behemoth of red brick.

Anyone can use the British Library, but to access the books, I had to become a registered reader. Rosa already had a membership card so while she deposited her belongings in a locker, I queued up to enrol. Registration is a simple, if time-consuming process that only requires proof of need: I had come equipped with a list of books I couldn’t access anywhere else, not in the whole of Oxford nor the whole of England. I mentioned Beowulf and Renaissance tapestries and a copy of a photography album, and shortly thereafter, I was issued a mint green card printed with a glorious portrait shot flatteringly from below. Ours was an inconsequential afternoon and that day passed like so many other days spent in the library: quietly and slowly, with maybe a short acceleration right before the reading room’s last bell.

More than seven years later I am, once again, sitting in the British Library where I have returned so many times, by cycle and by foot, pushing through crowds at King’s Cross, for short quick trips to use the toilet, for last-minute footnote revisions, for days of interminable writer’s block and computer crashes. So many days that my phone has learned not just to accept ‘BL’ but to suggest it. So much of research is reading widely and generously, which is why I love writing about contemporary art, as everything and anything counts as study material. I spent months learning about carnival, about the history of dioramas, about how exactly a Polaroid camera works, yet only slivers of this material concretely found their way into my dissertation.

Despite these years and hundreds of book requests, I have only gotten to know a miniscule part of the library, with all its oddballs and glorious quirks. I spent a week once looking through books of Helmut Newton’s photographs. These were not particularly rare but somewhat salacious, so I was sent to a special section. Across from me, a woman was perusing medieval medical treatises. Another was delicately thumbing through 17th century scores. And a row away, an empty desk was covered in books upon books about cats in art.

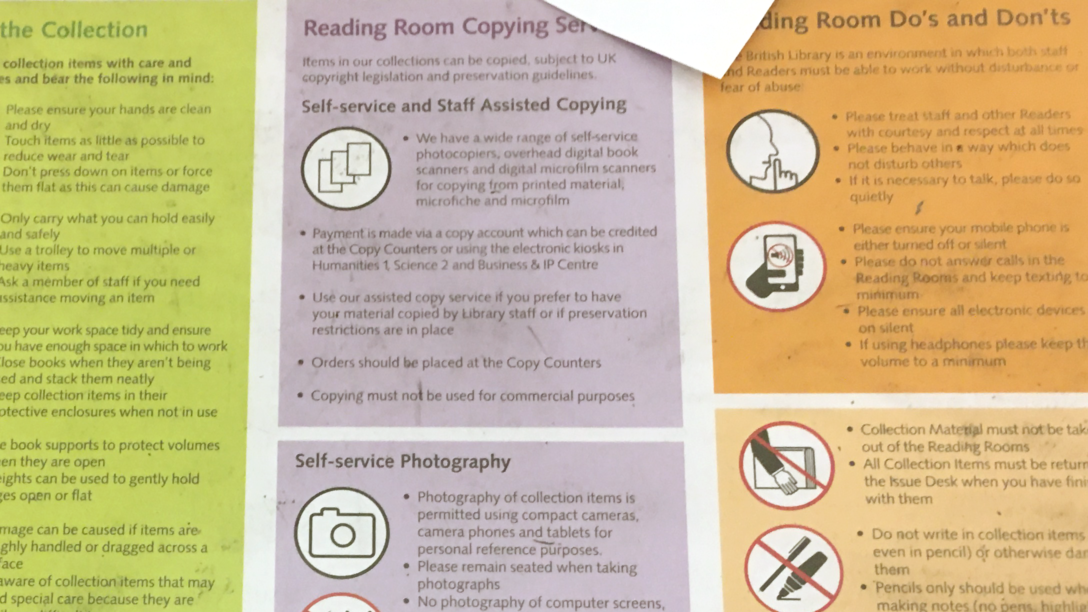

There are eleven reading rooms at the British Library; selecting one is a significant matter, because most end up returning to the same room again and again. Rosa and I spent my first afternoon in Humanities 1, a gaping space I would visit maybe twice more before settling elsewhere. Humanities 1 isn’t unpleasant: like all the other reading rooms, it comes furnished with plenty of large desks, each outfitted with a reading lamp, two electrical sockets, and a placemat outlining the Dos and Don’ts. And like the ten other options, it is also cavernous, bitter and draughty, but this is England where most libraries and classrooms ration heating as if the war had never ended. To dress for the British Library is to wear two jumpers and a blanket scarf. In the reading room today, everyone is bundled in hats and mittens. Somehow, there is a breeze even though the room is sealed off and the windows have never once been opened. As coats aren’t allowed, some have furtively layered down puffers beneath their sweaters. In the summer the rooms are equally cold, which is nice for the hot, thick days of July and August, but mostly miserable the rest of the time.

I participated once in a British Library focus group, and raising the ambient temperature was my main policy objective. I also wanted better seating options for where I could eat my packed lunch. This was a one-on-one interview, and I learned later that my responses were so extreme compared with anything anyone else had said that they were circulated amongst the consulting firm’s staff. I can only assume that other respondents see the library as a hallowed hall and not, like I do, as an office, laboratory, conference room, and therapist’s couch.

In addition to coats, beverages of any form, hand cream, backpacks, purses, pens, sneezing, phone ringers, highlighters, and Post-It notes are all either verboten or frowned upon. During the day, security guards casually roam the reading rooms looking for contraband to confiscate. Sometimes their prowl is cursory; sometimes it seems they have a quota to fill. I like these men and women who eye my ID when I enter and my plastic bag when I leave, and they too are the same faces, year after year. But their attention can be perfunctory and erratic. I have seen them spot a Bic across an expanse of desks but fail to notice a woman whose vape pen filled the room with vanilla clouds.

Regarding Humanities 1, I no longer sit there simply because I am not eighteen and trying to pick someone up in the library; nor do I necessarily want to watch these boys and girls try and fail to pick up each other. Instead, I moved around the reading rooms for a few weeks, giving Rare Books and Sociology a try, before settling in Humanities 2.

After spending nearly every waking hour there for close to four years, the librarians wave aside my ID when I go to collect my books. I know their faces and tics, the matron with carpal tunnel, the French woman who is always reading a novel, the man who gave me pencils when mine were broken. Sadly, our across-the-desk banter ended when he decamped back downstairs to Humanities 1.

I couldn’t possibly entertain the thought of leaving desk 3103. Switching would be rash and dramatic, tantamount to getting bangs after a breakup or betting one’s savings at the dog races. At this desk, I wrote the bulk of my dissertation. It was here that I fundamentally changed my entire writing style and approach, and where I would finalise all my image captions. Change was not a real option.

The British Library in its current home has been open for only two decades. Previously, the collection was part of the British Museum, where it had lived since 1857 under the round dome at the centre of the Great Court. Lack of space for an ever-swelling collection led museum trustees to propose expanding the library in 1951, and the project began development just over ten years later. But as the needs of the new library diverged from those of the museum, in 1966 the two institutions formally separated.

On June 25, 1998, the Queen opened the new library site, designed by Colin St John Wilson. As a legal deposit library, the British Library exerts a powerful gravitational pull, sweeping up a copy of every work published in the United Kingdom and a vast number of those printed abroad as well. Two decades on, the British Library is now home to almost two hundred million books, maps and objects, including the Magna Carta, a Gutenberg Bible, and documents belonging to nearly all faith and language groups.

There are few spaces anywhere that encourage the traffic of knowledge so freely and expansively, that value the pursuit of truth in all its brutal, uncomfortable beauty. Whole lives transpire here in the library. Babies who become flirty undergrads who grow into sweaty PhD students who mature into elbow-padded thinkers and snoopers. Whole lives lived with sniffly noses; whole lives sat together poring over books in a silent and frosty communion. For years, an old man with a terrible cough sat in Humanities 2 at the row of desks that run along the room’s terraced edge. He often wore a red jumper over a checked shirt and coughed away as he sifted madly through piles of papers. He no longer comes to the reading room, and I haven’t seen him elsewhere in many months. For years, his wet hacking made me brace tensely. Now I miss him.

To enter the British Library, one must pass through Wilson’s large piazza. On warm days, visitors and researchers spill into the forecourt to sunbathe and eat lunch. Undergrads splay out on the wide steps and picnic at the feet of Newton. Children race along the bricks. And in the mornings, in the minutes before the library opens, the forecourt is filled with a serpentine queue as visitors await a new and now-mandatory bag check.

Inside, they are greeted first by an enormous and ugly bronze bench cast in the shape of an open book. In a nod to libraries past where valuable texts were secured in place to prevent their theft, the book is held down by a ball and chain. The British Library is not and never was a chained library, though in its rooms a chaining of sorts does occur, of us, its patrons. It is a difficult orbit to extricate oneself from even if its fundamental forces appear to be governed more by whim than rule.

There is a guy I know vaguely, in the way that academia is small and we both studied art history, who finished his dissertation a few months before I submitted mine. He wrote his thesis from a desk in the middle of Humanities 2. After handing in, one assumed that he would leave the library for a while, freed as he was from arctic temperatures and permanently chapped skin. But he still comes in most days. He picks up his reserved books and sets up his laptop at the same old desk and then leaves to meet friends at the coffee bar; the British Library is his living room and social club. And I too am still here, even after submitting my dissertation and finalising the edits, despite the cold and my dry, scratchy tongue, and the fact that my pencils are always broken and the light too dim.