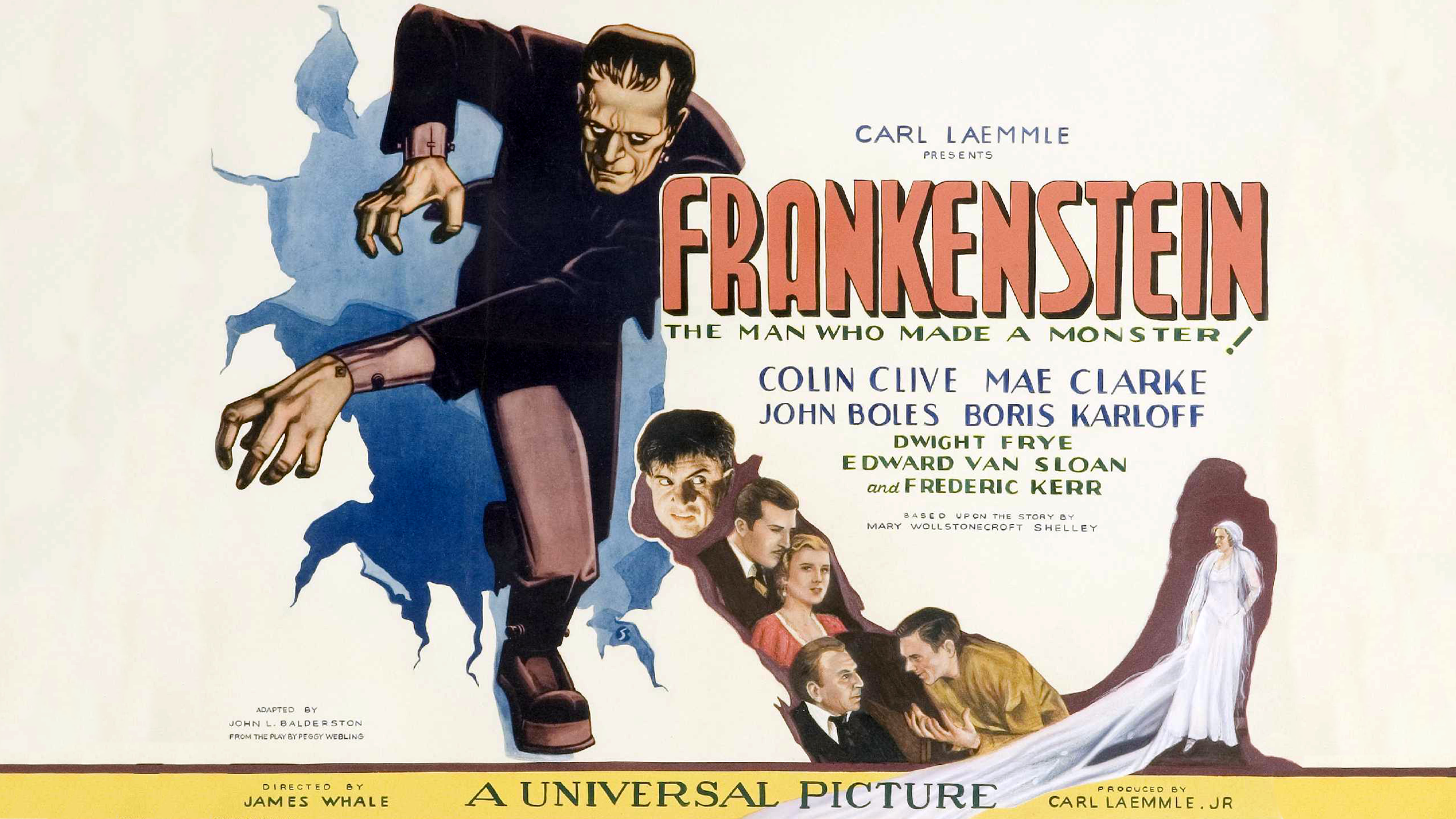

One day early in the term we were discussing the opening of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, and almost immediately the conversation turned to this Robert Walton guy; one student asked why Walton signs each of his first three letters differently: R. Walton, then Robert Walton, and finally R.W.

Are we saying that Walton’s identity is wobbly, right off the bat? I suggested. Another student wondered: what is this map doing before the title page? I’d read this novel six or seven times before, but had never given the map, with its straight edges and embossed place-names, much serious attention before now. A map suggests we know the place, several students replied; we control it—or we desire to control it. Why might a map be of use as we begin this novel? Well, we know that Robert Walton is on a journey, off to discover a north passage. Exploration is in the air. And on the page.

But the map that precedes the text of Frankenstein is strange: it doesn’t even come close to the north passage. It accounts for a later geography in the novel, the area around Lake Geneva.

The conversation was fast-paced, complex and spontaneous and exciting. I hadn’t planned for or predicted any of it. Our allotted 50 minutes flew by.

It was a dream class and yet, just an ordinary class: Sitting in a jagged circle; the invariably awkward start of the conversation; embarrassing silences;—all of us fumbling toward knowledge, confronted with something to read, interpret, learn something about.

It was also pre-registration time around then, which means I was advising students on how to navigate their paths to graduation. I’ve been noticing that more and more of them are saying, “Well, I guess I’ll take an online class or two….” This is code for not having to go to class. It’s a concession, of sorts. And it’s understandable: Many of our students are working multiple jobs to pay for tuition, and pressed for time. Online classes are delivered to them via their computers, their mobile phones. Delivery: that’s what administrators and support staff call it. Uber but for education, as if it will arrive in a box festooned with the semiotics of Amazon Prime.

Online courses cost the same: For instance, a student at my university pays the exact same tuition for an eight-week online composition course as for the same semester-long composition course “on the ground” (or “face-to-face,” depending on your institution). And an online course’s goals and outcomes are supposed to be the same as those offered on the physical campus. But most instructors will admit that the online experience is not at all the same as being in a classroom with students. And many will even confess that learning in online courses is patently inferior to learning face-to-face.

The word conversation came up many times when I asked my students what they thought about online classes, as the part that was missing. Here is a direct quote: “There’s so much pressure to have something formalized, which completely misses the point of conversation.” That is, while the expectations for discussion in an online class are in some ways higher, because they comprise some formal part of the grade, the online version of class discussion can’t compete with the real thing in terms of quality and nuance.

Online courses are mapped out clearly in advance. From the perspective of curriculum committees or strategic planning groups, I can see how they are attractive. But these classes, no matter how tightly designed and smartly delivered, can never deliver the magic of conversation—the energy and community dynamic such as I experienced teaching Frankenstein that day.

I’m not trying to set up or maintain a simplistic dichotomy between online classes and on-the-ground classes; I once naively tried to do that at Inside Higher Ed, and I got a lot of flak for it in the comments—which took on a surreal quality, ironically reflecting the worst of the internet in their very attempts to counter my claims.

There are innumerable ways, good and bad, to teach, both online and in a traditional classroom. But giving students the bland, neutral default of online learning results in an institutionalized depreciation of the classroom.

And not just the classroom in general, but of the kinds of unscripted, serendipitous conversations that can still happen in these spaces. The sincere excitement and pleasure of not knowing, but learning, together. The unpredictable, live, social production of knowledge, bodies squirming in seats, uncertain minds, feeling shy to jump in—feels all the more precious, almost mystical, as online offerings are made equivalent (and not just supplemental to) classes on the ground.

Classroom learning requires experiences of uncertainty, drawn out for seconds or even minutes—sometimes an entire semester can feel off kilter—but we’re increasingly accustomed to obliterating such time by reaching for our smartphones. There, we can find everything we need—and plenty with which to kill time even when we don’t know what we need; phones have become appendages, natural extensions of our bodies, and we use them to neutralize all the in-between moments in life: waiting for food to arrive; as passengers on airplanes; before the light turns green, in our driver’s seats; walking across campus….

And at this point, smartphones have thoroughly infiltrated the classroom. College students using their phones during class are not necessarily being defiant or rebellious; more and more, they don’t even try to hide their phones when they tap at them mid-class. They’re not ashamed. It’s just life, what they’ve grown up into. But it is becoming increasingly difficult for them to pay sustained attention in order to participate in class—to head willingly into the unknown (to borrow from Queen Elsa, our contemporary explorer of the north.)

Most institutions these days offer, and sometimes even require, online “learning management platforms” such as Blackboard or Canvas. These systems allow instructors and students to upload and access course materials, and conduct discussions—outside of, in tandem with, or even in place of a face-to-face class. They also accommodate grading and feedback. The automation enforced by these platforms mirrors the spread of platforms and apps throughout every aspect of life, from banking and shopping, to medical records, social media, and news delivery.

Despite having grown up online, my students have no love for these platforms. They’re not sold on the efficiencies promised by Blackboard or Canvas. At best, they just work. But either way, these things rapidly become just another app to keep track of, another website to log on to late at night, another password to forget; the Blackboard app is for them some kind of pre-work work vortex, just one more locus of drudgery in a hellscape of never-ending digital labor.

The slickly designed, familiar chat-box cascade on Blackboard seems to streamline and standardize conversation—and invite more voices in, even!—but ends up feeling halting, intimidating, and ultimately like a poor simulacrum. One of my students observed, “The more sophisticated your responses are, the less likely other classmates will engage with them.”

My students say they feel more pressure to produce content for these online discussion boards, even when they have lower expectations for the results of the exchange. And many expressed something like a numb acceptance of these platforms, which to be honest I found a bit rattling.

“It’s the Devil we know,” one of them concluded, rather chillingly.

Blackboard and Canvas, when adopted and normalized by institutions, transform all learning contexts into online learning contexts, to some extent. What matters is the continuous flow of content through the platforms. Fill up the Blackboard, paint the Canvas. The platform is indifferent as to whether the class meets in person or only online, as long as the online folders and subfolders are filled and accessed, files downloaded and uploaded. Sometimes there might be a discussion board, threads about a certain reading or assignment. But, as my students hinted, don’t confuse this with a conversation.

Students also mentioned their discomfort with the surveillance aspect of Blackboard, which registers when they are online, when and for how long they take a quiz, etc. I hadn’t thought about this before, but what use is being made of this information, who is selling it, why and to whom?

Handwriting in terrible script, written in real chalk on the blackboard; awkward lapses after a question has been raised; writing together in the moment, on pieces of paper—these things feel clumsy and slow compared to the online educational utopia, compared with our own little rectangular super computers, compared with the procedural sublime of the online interface and its promises of data-driven achievement and measurability.

There’s something profoundly humbling about being in a classroom with other learners, and with a teacher, working together. There’s really no map for it, no way to measure it in the moment. This is an an ineffable yet crucial part of the learning experience. The classroom interrupts the normal patterns of activity—specifically with regard to being online, creating and consuming content.

In the classroom we are reminded daily of the processual, meandering, stop-and-start nature of learning. Its human aspect, its avenues of mystery and surprise. The unknown is right here, in the real classroom, and we must not lose sight of it.

Maybe I have fallen back into a dualistic position, here, arguing for the inestimable value of “face-to-face” conversations and “on the ground” classrooms, against the new digital ecosystem of online learning. But if conversations dry up, any value that all that educational content may have had will evaporate with them. “Online learning” will turn out to have been a false paradise—not so unlike Robert Walton’s imagined temperate climes of the far north.