When I was ten, I told my parents that I wanted to marry the president. I couldn’t quite read their reaction; something between amusement and disgust. It was a while before I understood why they gave me that look.

I grew up in communist Romania, during the rule of Nicolae Ceausescu. Every day in class, I stood up to sing the national anthem facing the flag; he smiled a kind, lopsided smile at me from the framed picture above the blackboard. His face was on the first page of every single one of my school textbooks, it appeared in gilded frames in paintings, it was on every TV report in the evening; his voice was everywhere on the radio waves. It was hard not to fall in love.

The Western stereotype of life under a communist dictator like Ceausescu is a long nightmare of fear, hunger, and police brutality. I am sure that was the case for some. But life was extraordinarily ordinary for many of us children. We played, we went to school, went to summer camp or travelled with our families. The streets were safe and education was taken seriously; schoolwork kept us quite busy. My parents were neither communist apparatchiks nor dissidents; like most Romanians, they navigated the system the best they could, merely trying to live their lives in peace. During the 1970s, things had been good in Romania, but by the 1980s Ceausescu decided to pay Romania’s debts to the IMF by exporting as much as possible. It became hard to even find the bare necessities of life. Food was rationed, and there were long lines for everything. My mother had to wake up at 2 a.m. to leave two empty bottles in the line; at 6 a.m., when the milk truck arrived, she’d wake up again and go to the store to buy the milk.

Certain life arrangements were strange, for sure, but I could remember nothing else and took everything in stride. Very few people had phones, but we could drop in to our neighbors, and I’d go to hang out with my friends, even unannounced. Even fewer had cars, but public transportation was available and cheap. The power always went off around 11 a.m. and came back at 5 p.m. In the winter, it got dark early, so I had to finish homework before dusk or I’d be forced to read and write by candlelight. It was also quite cold in our apartment during the winter; the heating came on only intermittently, so we huddled in the kitchen and made fun of the situation. One joke went that people who lived on the first floor were forbidden to open their windows in the winter, for fear that passers-by would catch a cold.

There were only two TV stations that broadcast a couple of hours every day—mostly news about Ceausescu—but you could now and then see some Tom and Jerry cartoons. When nothing good was on, my dad would climb on the roof of the apartment building and wiggle our antenna until we could get reception from the Yugoslav or Bulgarian TV stations across the Danube, and we watched Miami Vice or old Westerns. You could even buy blue jeans and western music if you lived close to a border. I remember showing off my first pair of blue jeans in middle school; I had bought them in a small town on the banks of the river, where Yugoslav smugglers brought their wares.

I also somehow learned not to discuss politics on the playground or at school. Or to mention that my father sometimes listened to Voice of America. Or to tell political jokes. How, I don’t quite remember. As children, we were not told about the Secret Police, the re-education prisons, the work camps, or the everyday hardships our parents had to deal with in order to put food on the table. We also did not know about the luxury in which the Ceausescus lived, golden bathroom and all, while most Romanians were allotted half a loaf of bread per day. All that hit my consciousness much later. At the time, the warm wave of propaganda enveloped all aspects of my childhood, giving it structure and meaning.

In second grade, I became a Pioneer. My parents bought me the uniform, the neck-scarf, the belt decorated with the national crest. I felt very special. Alongside all the second graders in my school, I took the Pioneer Oath and joined the thousands of Romanian children regimented in a nation-wide organization that had been steadily growing since its creation after World War II—by 1982, The Pioneers had over two million members. Ceausescu was the designated recipient of our unconditional love and adulation. There were set phrases we were supposed to use when talking about the president; he was the ‘genius of the Carpathians,’ ‘the hero of heroes,’ ‘father of the fatherland, and defender of our freedom;’ he was the country’s ‘first architect,’ and ‘the worker of workers.’ Some of these phrases were quite a mouthful, but we somehow managed.

There was an ahistorical logic in Ceausescu’s pedigree; although he was in fact a semi-illiterate peasant, he was presented as a descendent of the Dacians and the Romans, the earliest ancestors of the Romanian people. By fifth grade, I could almost see the similarity to Julius Caesar in his tall forehead and the shape of his earlobes. The entire trajectory of national history culminated in his presidency; he was equal with the kings of olden days. It was all very glamorous, if politically inconsistent, but we did not know the difference between monarchies and republics, and would not have cared anyway. Even geography classes confirmed how special our country was, just like its supreme leader: Romania was perfect. The country had a perfectly moderate climate, with a perfect variety of relief: fertile fields, sunny hills, snow-capped mountains, the Danube Delta and the Black Sea coast. It also had virtually endless natural resources, from gold to oil. I was almost grateful to Ceausescu for all that too, as if the president were responsible even for the geography and natural resources of the country.

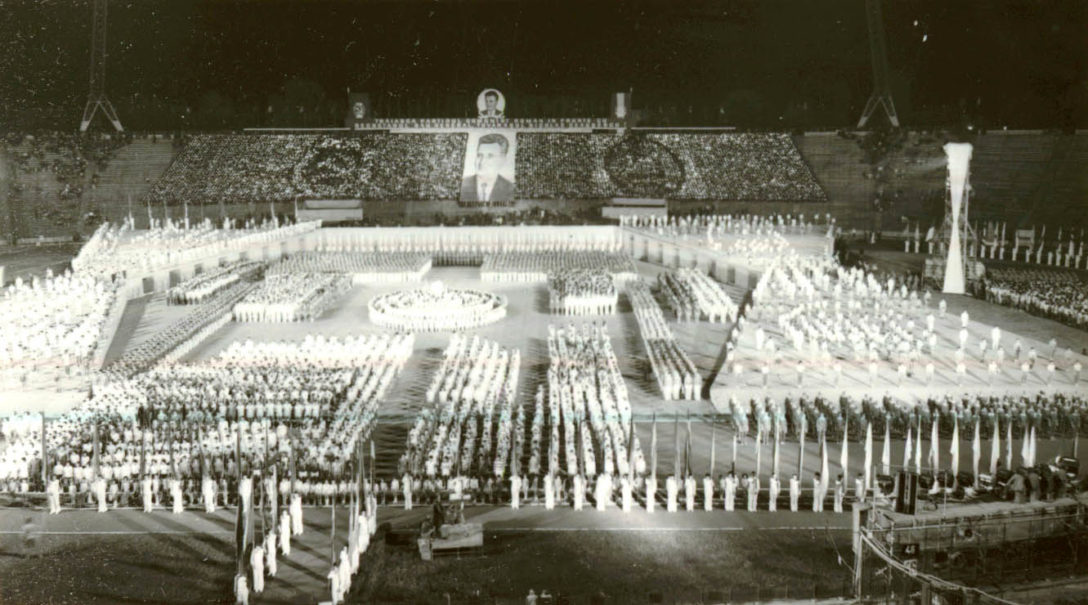

Periodically we were taken out of school to march in parades and recite poems to the dear leader; we sang songs, held flags, stood in the hot sun celebrating the national day, August 23, and were generally excited to be out of the classroom. We also believed—at least a little—the things we had been repeating all our lives. We had to thank the president for the wonders of our childhood, even when he was not physically present: Ceausescu micromanaged everything in the country and therefore had single-handedly brought about Romania’s ‘Golden Age.’ Probably, because he was a genius, he could give recommendations on anything, from school textbooks to the architectural style of public buildings: even the megalomaniacal Palace of the People, the world’s third largest public building, had been built based on his ideas. Ceausescu must have even been an expert in baking: I remember seeing him on TV visiting a bakery, assessing the quality of the loaves and giving advice to the workers. In short, the leader was everywhere and we, the Pioneers, had the duty to worship him and worship the country; our lives were his gift to us.

Like all autocrats, Ceausescu was in it for the long haul. He came to power in 1967, and by the time I was making my declaration of love he had been president for two decades. There was hardly an area of public life untouched by the cult of his personality: three generations had lived their childhoods under his watch.

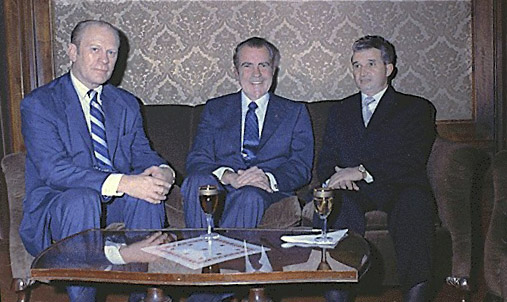

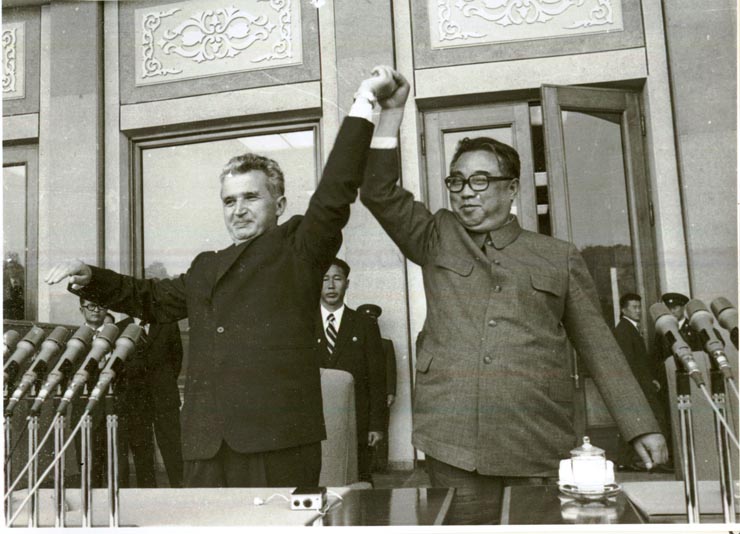

Ceausescu was of a special breed among communist rulers—a nationalist, rather than an internationalist. He stood up to Moscow, refused to join in the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia, and criticized the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. All this made him the darling of Western leaders. American and British leaders courted my dictator; Nixon visited Romania in 1969, and Ceauşescu went to Washington several times, at the invitation of presidents Nixon, Ford, and Carter. He was even knighted by Queen Elizabeth, although she later regretted it and withdrew the knighthood. In 1971, he visited North Korea and was awed by the cult of personality surrounding Kim Il-Sung’s presidency. He came back determined to get the same thing at home. It was all downhill from there.

Romanian National Archives, ID 44994X201X390

fototeca.iiccr.ro

Romanian National Archives, ID 44994X201X390

fototeca.iiccr.ro By the time Ceausescu was deposed in December 1989 I no longer believed in the stories about his greatness, but I did not really hate him, either. I remember watching his execution on TV, a rather gory Christmas Day broadcast. I was scared, because I knew there was shooting in the streets, but vaguely wondered whether killing him was really necessary. At the end Nicolae Ceausescu seemed harmless, a puny, shriveled and incoherent old man, quite unlike the vigorous presence that had loomed over my childhood years.

Fast forward thirty years; I am now living in the U.S. and I hardly think about Ceausescu anymore. Yet I feel his shadow in my instinctive reaction against anything that smacks of nationalist propaganda. And, to me, my new country seems awash in it; from the profusion of flags on every street, lapel pins and bald eagle paraphernalia, or the quasi-military chanting of the national anthem before sports events. The character of my childhood makes the sight of a whole stadium standing up and chanting in unison “The Star-spangled Banner,” hands to heart, a frightening one. Election season, too, is disturbing; I am perpetually baffled by the politicians of all stripes who routinely declare, with a straight face, the absolute greatness of the American nation above all others. Are these displays of American patriotism in any way different from the nationalist propaganda I experienced as a child? Do they work differently on the psyches of American children?

I also wonder about what it must feel like to be a child in the United States these days. How does the constant narrative of American exceptionalism that pervades political culture and social ritual work with or against the visible efforts to promote critical thinking in schools? How are American children negotiating their collective identity these days, given the divisive rhetoric and conflicting messages around the concepts of “freedom” and “democracy”?

As a child I can remember brief moments when I grasped the contradiction between doing homework by candlelight and hearing Ceausescu on the radio speaking about Romania’s Golden Age, but usually I quickly pushed the thoughts aside. Do American children struggle with a similar kind of cognitive dissonance? Perhaps the desire to cling to an image of uncritical American greatness in the economically depressed areas of the country can partially explain the popularity of President Trump and his rhetoric. Perhaps the logic of ‘if you build it, they will come’ works not only for wildlife and urban development projects, but also for nationalist propaganda and dictators: build an infrastructure of belief and dogmatic thinking about the nation, and sooner or later someone is bound to come and weaponize it.

When that happens, facts no longer matter, because the propaganda version of the truth is freely chosen. I don’t know. I may research, teach, and write about American culture and I understand its dynamics on an intellectual level; emotionally, I will always still experience it through the filter of my own childhood. Which means that I will probably continue to cringe whenever the Boy Scouts parade around the room in their uniforms saluting the flag, and I will continue to fidget at every Pledge of Allegiance and every national anthem sung before a sporting event.

Is this really propaganda? Or is it just my own dictator playing tricks with my mind, three decades later?