After almost two months, the nationwide lockdown has ended here in Italy. We have now entered the so-called “Phase 2”, which is a bureaucratic expression meaning that we can no longer afford to keep factories closed, even though we still register hundreds of COVID-19 deaths and a thousand or so new cases every day. So once again we are fulfilling our role as the Australia of the Coronavirus crisis: the first country to enter a new phase in a rain of fireworks, and show the others what comes next. We’re among the first countries to start living the “new normal” we all kept predicting would come back in February. The difference being that other countries cautiously attempting to “open,” such as New Zealand and South Korea, have apparently managed to contain the spread of the virus extremely well.

There’s no question that keeping people inside was becoming more complicated every week. Italy’s lockdown has been so strict that people weren’t allowed outside even for exercise. Consequently, everyone was out of his mind. Me and my girlfriend used to argue so rarely before the lockdown, but in the last month, we’ve found ourselves increasingly prickly with one other. Generally speaking, everyone was becoming more and more annoyed by the mere existence of everyone else. Even the new trend of doing Skype call during the aperitivo—there’s a new word for it, Skyperitivo—at last peaked; video calls became increasingly terrible. I deliberately missed two in two days with my father, and skipped a family Zoom meeting last weekend. It’s tiring, increasingly consuming, one hasn’t the mental energy to bear it.

Being always overworked didn’t help. My daily routine during “Phase 1” or total lockdown went like this: waking up, working from my bed, eating, working from my couch, eating, going to sleep. I often thought about Mark O’Connell’s book about transhumanism, To Be a Machine, and thought that maybe Zoltan Istvan and his peers should try working from home during a pandemic, without being able ever to go outside. Day by day, I was becoming less able to live this way, and sometimes I’ve found myself banging my head against the headboard after reading an email from my boss, which is a totally normal way of dealing with work. So the easing of restrictions was probably to some degree necessary: there must be a lot of people in my situation right now, and at least starting this week we can go for a walk and choose exercise over self-harm.

But on the other hand, “Phase 2” will probably end badly. Or rather, already we know it will. The disease is still raging; we merely managed to halt its spread by staying home, and beyond that, nothing more has been done. There is no mass testing, no contact tracing, nothing. And now we’re all going out again. You don’t need to be a virologist to realize that the situation will worsen very soon. On top of which, as usual, the new rules for going out are a mess, so basically everyone will do what they want and hope to avoid getting caught. For example, the government has decided to let us visit family and loved ones, but their announcement used the word “congiunto/i”—which can include any person you deem important in your life—and then tried to clarify, using the expression “stable relationships” plus some FAQs attempting to explain what they mean by it. The result was a lot of confusion and a few memes, like the one where a police officer stops a car and asks the driver, “So, do you really love this girl?” in order to decide whether to fine him or not.

So, while we’re happy we can finally see our congiunti again, after two months that felt like two years, we also have this feeling of living through an intermission in the same tragedy, of watching a car crash in slow motion. This feeling that we’re cheering right now, but we’ll regret it tomorrow.

In the first day of this “Phase 2” deal I went to see my brother and my sister, we drank a beer on the balcony of his house, we noticed how we’d all changed during the lockdown, and were really happy to hang with each other again. But a part of us was already thinking about what will come next, and finally, truly, realizing how long this thing will last.

Last January, just before everything started, my sister booked a flight to Mexico for next summer. In February she postponed the trip until December; only now has she realized that even that will probably be too early. My girlfriend has a villa in the countryside of Tuscany, with a pretty big garden and a little pine grove; we rarely go there because we’d rather spend our summer holidays backpacking abroad, but now we’re craving the day when the restrictions of movement between regions will be relaxed and we’ll be able to leave Milan and move there, where we plan to stay until the pandemic is over. We’ll live through a real-life version of The Decameron, after all, even though we’re starting a bit late.

Most of all, the end of the so-called “Phase 1” of the emergency has forced us all—as a country, as a society—to take stock in these first months. We did this by ourselves, a fact which I suspect the media and the government have not really grasped. Following the news nowadays, it looks like business as usual: yes, there’s a pandemic; yes, the worst is over; yes, we’ll soon be able to re-open everything and “go back to normal.” You’ll hear about how to save tourism, how to go to the beach safely in a couple of months, and about how to pay for it (they’re talking about a ‘holiday bonus’ of 500 euros from the government). But all this talk is pretty far from the reality of what is happening here.

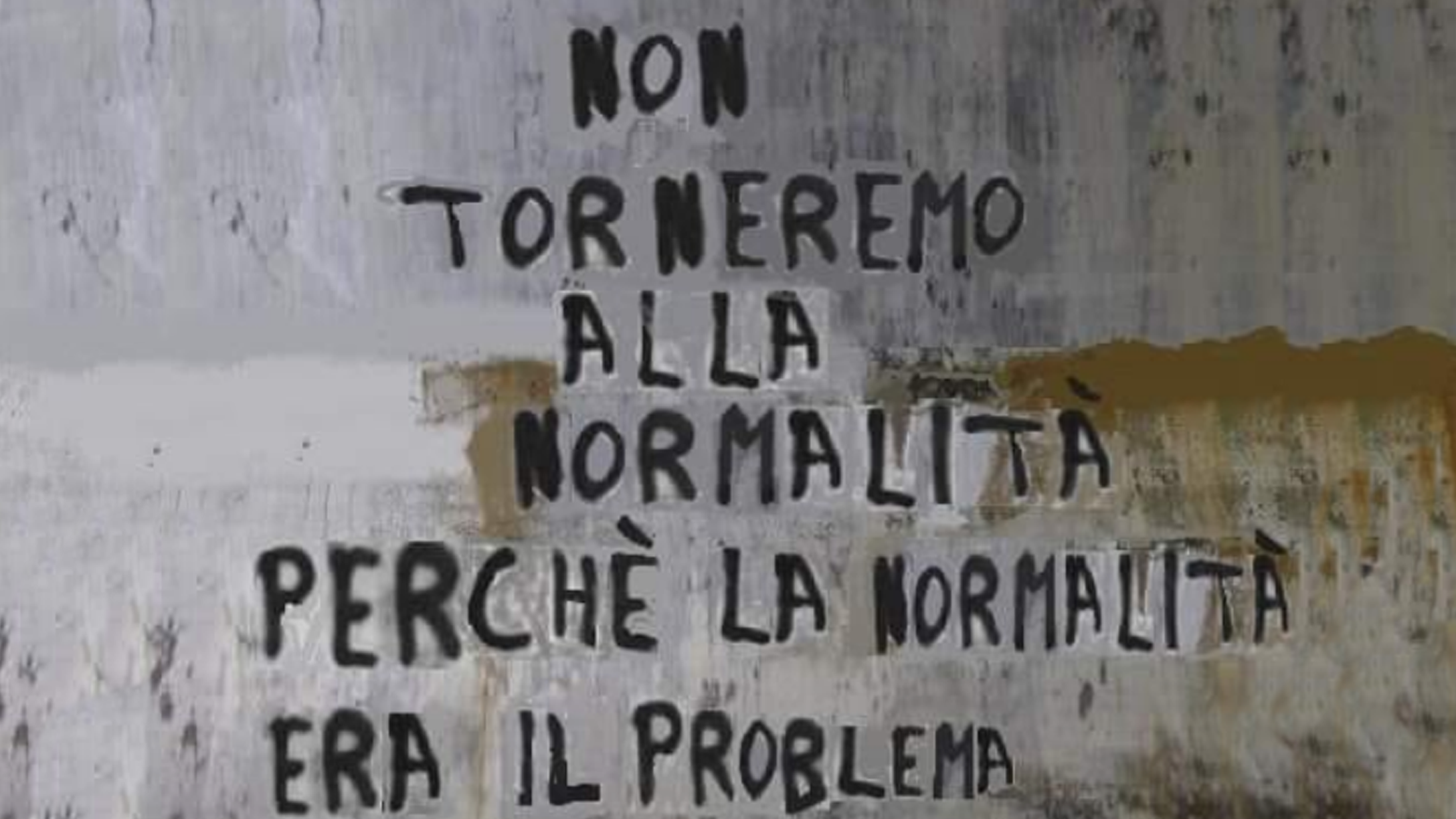

I don’t think ordinary people are very concerned with going to the beach right now, or if they are, it’s probably as a way to escape from the troubles and the pain of this moment. A friend of mine, who joined one of the many “solidarity brigades” set up to help people struggling to make ends meet, told me yesterday after his first shift in a public housing block: I’m almost vomiting, I’m really angry that this has always been normal. That reminded me of a slogan we see more and more often, shared on Facebook walls or painted over real ones, a slogan of the post-pandemic world:

“We won’t go back to normal, because normal was the problem.”