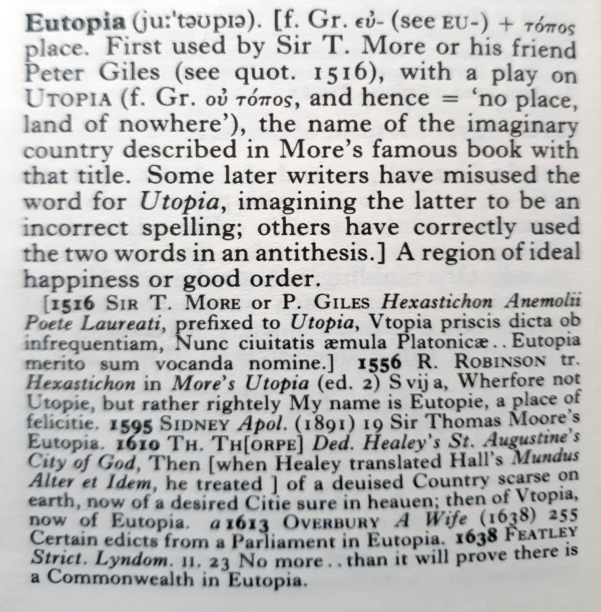

“A utopia is a place that exists but one that is simultaneously not real,” said my grey-bearded English professor, “meaning it can exist only inside your own mind, and it is down to you to decide what you do with that.” The word “utopia” derives from the Greek ού meaning “not,” and τόπος meaning “place”, combining to make “a not-place,” whilst the English homophone, “eutopia,” stems from the Greek εύ meaning “good.” The Oxford English Dictionary gives an interesting comment on the dual etymology:

detail: Oxford English Dictionary

detail: Oxford English DictionaryI studied politics at university, where I’d found much of the coursework to be reinforcing of the political status quo at the expense of more imaginative thinking, so I jumped at the chance to take an English literature module focusing on utopias and dystopias. It had a profound effect on my thinking, encouraging me to find political relevance and inspiration in fiction, which soon led me to Ursula K. Le Guin and The Dispossessed.

Utopian societies in fiction rarely turn out to be as inviting as they first seem. It is a pattern centuries old; the utopia degenerates into an abominable society—or else it had always been abominable, and the reality had been hidden from view. Le Guin breaks the mould with Anarres, her imaginary society in The Dispossessed. Rather than attempting to prove utopias are impossible, she encourages us to reconsider exactly what it is that we view as one. Anarres is a believably flawed society, but one built on solidarity and equality.

Isaac Asimov once remarked that “science fiction is important because it fights the natural notion that there’s something permanent about things the way they are right now.” The Dispossessed presents us with, in Le Guin’s own words, an “ambiguous utopia.” She shows us not only that another world is possible, but that we know how to build it.

The novel’s protagonist, Shevek, and his friends struggle to understand prisons, which they know of only through textbooks; one of the group volunteers to be locked up. When he is eventually freed, he has soiled himself and is emotionally traumatised. The experience awakens in Shevek an understanding of the violence that power can hold. By this simple means, Le Guin effortlessly conjures a life lived at odds with our own. In many ways, our current world is beginning to open these avenues of vision too.

Across the globe, longstanding economic and social norms that had seemed set in stone are crumbling in response to COVID-19. Iran released 85,000 prisoners, Indonesia 22,000, and similar measures are under consideration in many other countries. In an analogous way to Le Guin’s concept of a society with no prisons, the pandemic has forced all to ask serious questions of the status quo: If these people are no longer considered a “danger” to the public, then for whose benefit were they locked up? While I would have classed myself as belonging to the political “left” when I first read The Dispossessed, Le Guin pushed my political vision beyond the hope of merely tinkering round the edges. “A different world is possible,” it said to me, “why not chase it?”

If evictions can be suspended because they make people vulnerable, why was this never on the table at any other time? If homeless people can be housed now, why were they not already? If you can do your job or continue your studies from home, why were these accommodations previously denied, for example, to disabled people who needed them? The pervasive attitude that capitalism—and neoliberal capitalism more specifically—is the only possible economic system is suddenly losing its grip. “It is easier to imagine an end to the world,” the late Mark Fisher once said, “than an end to capitalism.” But now everyone is imagining it, out of sheer necessity.

In The Dispossessed, Shevek gives a speech to revolutionaries on the capitalist dominated planet of Urras: “We have no states, no nations, no presidents, no premiers, no chiefs, no generals, no bosses, no bankers, no landlords, no wages, no charity, no police, no soldiers, no wars. Nor do we have much else. We are sharers, not owners. We are not prosperous. None of us is rich. None of us is powerful. If it is Anarres you want, if it is the future you seek, then I tell you that you must come to it with empty hands.”

As the world’s governments dragged their feet in response to the pandemic, mutual aid groups are stepping in to fill the void, delivering food shops and prescriptions to those self-isolating, and crowdfunding for those who cannot afford necessities due to job losses. Time and time again we find that solidarity exists most profoundly among those with the least.

In Walter Benjamin’s posthumously published On the Concept of History, completed shortly before his suicide, he writes of a painting by Paul Klee named Angelus Novus. It is a funny looking thing, but in Benjamin it provoked a profound thought:

Angelus Novus shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing in from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such a violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward.

We ourselves may feel that we are now the angel of history—condemned to watch the wreckage pile up in front of our eyes, helpless, never able to reach out and “make whole what has been smashed.” But this needn’t be the case.

As a child, Shevek is taught that “nothing is yours. It is to use. It is to share. If you will not share it, you cannot use it,” the central tenet that guides the people of Anarres. Conditions of scarcity require a strong sense of community and a commitment to others, and this is something we all surely feel in our own world, right now.

To see life through different eyes is, for me, the only way to ward off the feeling of powerlessness. To know that our society is barbaric and unnecessary, and that it will not last forever, does not necessarily inspire the imagination of a better one. The power to transport you into a new world, one with social and political norms that conflict entirely with ours, cannot be understated. This is Le Guin’s greatest work: the creation of an “ambiguous utopia,” an imperfect and improvable reality, but one that is beautiful and superior to our own.