The most striking feature of our apartment in the Chelsea Hotel is the paintings. They are on every wall, in every room. Each one represents a different period of my father’s 60-year career as a painter: Alhambra period, The Fields, The Warriors and so on. The lion’s share are in the bedroom with me, in stacks of five or ten against the wall opposite my bed. In my spare time—which I have a lot of, now—I go through them. I study the compositions. This is how I think about my father: George Chemeche, an Israeli artist and author who came here in 1971. I see how he experimented with what kind of artist he wanted to be as a young man in the 1950s. Through the portraits of his first wife, Mira, I’ve come to understand how much he loved her in the 1960s. And I feel the energy and excitement of his ambition when he first came to New York City in the 1970s.

My father is living in the main part of the apartment, separate from me in the bedroom. Because of Covid-19 and the necessity to self-isolate, we barely see each other. He is hard of hearing, so we largely communicate through email now. Through studying the paintings, I am trying to learn about him as best I can. To overcome the new barrier between us. To feel who he was and appreciate who he is, while putting from my mind the possibility that I might lose him. Perhaps not through this first wave of the outbreak but, I fear, through the second one the news tells me is coming in the fall.

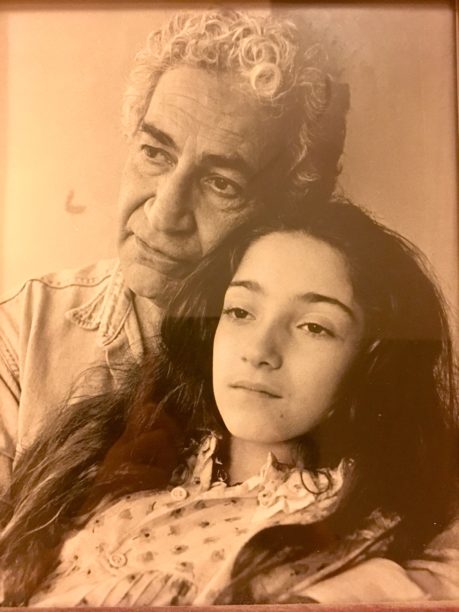

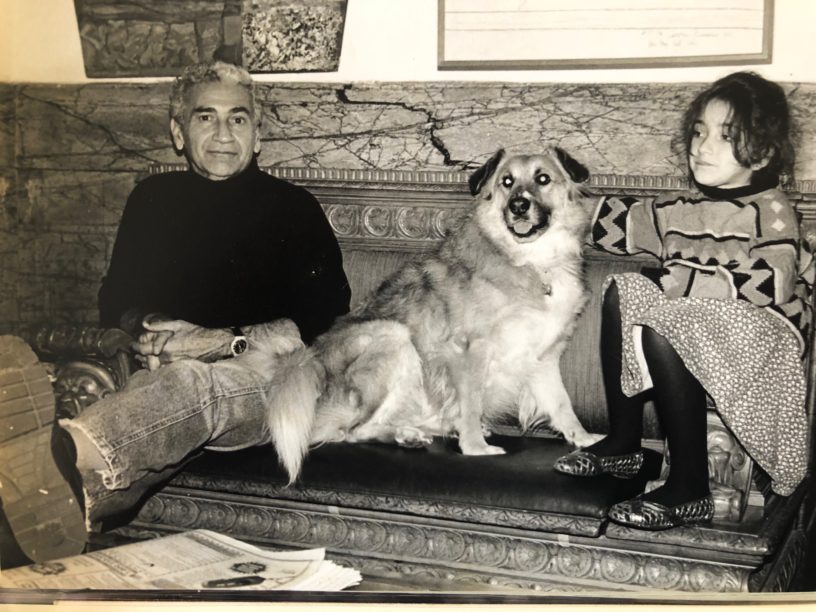

The other half of the apartment consists of a living room, TV room, kitchen and a second bathroom. There is a Murphy bed hidden behind a Persian carpet next to the fireplace. There are several hundred African fetish statues with protruding breasts and erections, pages of 16th and 18th Century Qurans, and ancient weapons lining the walls. In between are pictures of my dad as a young man, a nude of a woman who was his lover, me as a little girl.

Only fifty of the three hundred rooms in the Chelsea Hotel are occupied. The building has been under renovation since 2011. There are big, red duct tape X’s criss-crossing the front doors of the empty rooms; industrial steel padlocks seal them shut from the outside. It’s an empty place. Over our front doors, the doors of the occupied flats, are long sheets of plastic meant to keep out the filth and detritus of construction. They sway like ghosts.

The whole building is an echo chamber. The floors and stairs are made of marble. The staircase, which climbs through the center of the building like a great spine, spirals up ten floors. Without the buffer of a larger population of tenants and guests to absorb all the sounds—footsteps, laughter, the wheels of a cart, the bark of a dog—they bounce through every corner of the building. It’s been this way ever since the renovations started. But, with the onset of the pandemic, the closure of the city and the mass quarantine of the population, there is a new tension in this hollow place.

I used to see nearly all of the residents on a weekly basis, and was intimately familiar with their various projects, eccentricities and antics. But ever since the lockdown, I haven’t seen most of them in over two months. How are they, physically, mentally? Over the last years I’ve seen many residents pass away or disappear from the building. I am in an interminable state of waiting to learn what’s next.

On March 20th, the issuance of stay at home orders from Governor Cuomo and Mayor de Blasio emptied New York’s streets of their characteristically teeming, bustling population. The Hotel is situated on 23rd Street between 7th and 8th Avenues. The wide, long blocks of 23rd Street, one of the longest blocks in New York City—usually thronged with people, day and night—are empty. Storefronts are dark, some boarded up with plywood. It is a shade, a macabre skeleton of the riotous, chaotic city I love. Suddenly, the outside world matches the interior of the Chelsea. To step through the lobby of the ghost town I occupy into this ghost city is fractally destabilizing, a strange, haunting series of echoes.

It was such a familiar feeling, being so shocked by the abrupt change in one’s environment and circumstances while also knowing there is more to come. Of bracing yourself for more, but not quite knowing what you are bracing for. And of watching people suddenly disappear. You only find out afterwards, once they are gone.

Over the nine years following the first evictions, many Hotel residents, most of whom were elderly, were evicted. Others died. They’ve often departed into obscurity, their belongings packed up by Hotel staff and thrown into a dumpster. Storme DeLarverie, a biracial drag king and bouncer, who was a key gay rights figure in the Stonewall Riots, disappeared in 2011. I didn’t know where she went, or that she’d been evicted from the Hotel under allegedly false charges that she had a gun in her apartment. One day she was in the lobby speaking with me, sporting a glamorous set of brass knuckles in the shape of an eagle, and the next, she just wasn’t. She was committed to St Vincent’s, I later learned. I only found out what happened to her when she died in 2014 and I saw her obituary in the New York Times.

The Chelsea Hotel was designed by the architect Philip Hubert and opened in 1884. It was one of the first cooperatives in New York City, intended from the first to house rich and poor alike, with particular provision made for artists. Dylan Thomas, William Burroughs and Eugene O’Neill lived and wrote here in the 1950s. When Stanley Bard inherited and took over the management of the building in the 1960s, its history as the international bohemian capital of sex, drugs, and rock and roll began. Edie Sedgwick, Yves Klein, Arthur Miller, Bob Dylan, and members of the Velvet Underground, including Nico and John Cale, lived here, and so did Viva Hoffman, Valerie Solanas and other artists connected with Andy Warhol’s Factory. In the 1970’s, Robert Mapplethorpe, Patti Smith, Alan Ginsberg, Janis Joplin and Leonard Cohen came to stay. Smith’s memoir Just Kids paints a memorable portrait of life at that time.

By the late 70’s New York City was close to bankruptcy, and a new wave of artists as well as prostitutes, travelers, and drug addicts joined the mix to make the Hotel a grungier, more volatile place. In the 1980’s Sid Vicious stabbed Nancy Spungen in their room on the 1st floor. And during the relatively tame 90’s, Joseph O’Neill, Rufus Wainwright and Ethan Hawke lived here. Prior to 2011, in fact, no one would have called the Hotel a quiet place. At all hours, it vibrated with the myriad sounds of creation, hysteria, joy and tripping. During my waking hours I did my best to contribute to it, and when I went to bed it was the ambient noise that lulled me to sleep.

I was born in 1987. My father was 60 years old, and my mother, a Pennsylvania Dutch singer for the Metropolitan Opera, was 32. I spent time with Gabby and Viva Hoffman, Arthur Miller played with me and Dee Dee Ramone pelted me with quarters on Halloween nights when I dared to ring his doorbell for candy. The Hotel closed when I was 24—which was when I learned the importance of safeguarding the histories of elderly people. When I learned how quickly they can disappear.

On August 2nd, 2011, a team of men hired by Joseph Chetrit, the real estate developer who’d purchased the building, marched through the Hotel and knocked on the doors of guests, telling them to leave immediately. They stripped the lobby and walls of paintings belonging to past and present residents. They locked the door to the rooftop garden shut. The Hotel staff—concierges, cleaning ladies, janitors and others—were barred from the building and told to go home until further notice. Within twenty-four hours, the 100 remaining permanent tenants, plus a skeleton crew in the employ of Mr Chetrit, were all that remained. Suddenly, the halls we’d strolled up and down like boulevards, the garden and lobby where we’d congregated, the servants’ stairs and fire escapes where we’d kissed and smoked and so on, these were made alien and inhospitable to us.

On Instagram, Facebook and Zoom I learn that some residents are producing work in response to the pandemic, defying the disease and celebrating life through art.

Martine Barrat is a photographer who’s dedicated the last 50 years of her life to documenting people in Harlem. She has close-cropped hair, wears blue eyeshadow and pink glasses, tutus and leather pants. She was an actress and dancer back in the 1960’s. Nowadays, she has taken to documenting masked streetgoers. She takes snapshots of two men playing chess in the park; a vendor displaying his masks on a line of eerie, disembodied Styrofoam heads; a woman whose neon mask matches her neon hair.

The Queen of the Night, event producer Susanne Bartsch, hasn’t stopped throwing epic parties or wearing wild costumes during the lockdown; she just took her scene to the internet. I can hear the clack of her platform heels as she struts down the halls, modeling for her Instagram fans. In one picture, she’s wearing a diamante-studded face mask, a glitzy top hat and enormous cat eyes. She’s transported Bartschland Follies online with new Thursday night parties titled, “Susanne Bartsch Wants You ON TOP Online,” where she’s been gathering with nightlife celebrities and performers to dance and sing.

screenshot: Instagram

screenshot: InstagramBut these are the technologically savvy Chelsea Hotel residents, the ones who had internet followings prior to the pandemic. Others, many of them older veterans of the era of “sex, drugs, and rock and roll,” are not attuned to social media, or connected electronically. Yes, a lot of artists are used to living in complete isolation, working at home for hours alone. Now this lockdown has gone on for months, uninterrupted, with chaos raging outside. When I reached out to ask remaining residents if they were all right, responses varied wildly—from courteous to profound, from eccentric to offensive.

Choreographer Merle Lister came to the Hotel in 1962 when she was just 23. An important avant-garde choreographer, she established her own company in the 70’s that performed at Lincoln Center, in Central Park, and at the 92nd Street Y, to name a few places. For the 1983 centennial celebration for the Hotel, she choreographed “Dance of the Spirits.” For the past twenty years or so, she’s developed a new role as the keeper of legends. As the resident storyteller here, she holds court near the front door, ready to tell eager tourists about the glory days of the building. Now she is in seclusion like the rest of us, but still telling stories, giving interviews from her room.

“I’m fine, I’m fine! Did you hear about the documentary they are doing about me? Two Belgian girls are doing it, yes! It’s all about my life.”

“You know, all of this is transitory,” Gerald Busby told me, in his honeyed, Southern voice. “You just need to be in the present, meditate on this experience, and continue to work.” He is a composer and protege of Virgil Thompson. A musical prodigy, he grew up in a Baptist family in Texas, played piano with the Houston Symphony when he was fifteen, and studied philosophy at Yale. He first worked as a traveling salesman and then, when he was forty years old, turned to composition. In 1995, he lost his partner to AIDs. Afterwards he started taking lots of drugs. “You have to understand, back in those days, if you had HIV, it was a death sentence. I thought I was going to die and I’d just lost my lover. So I thought, why not go out with a lot of drugs.” But he survived, stopped taking drugs and began composing music again.

One resident was less interested in talking with me, screaming “Fuck off!” through her door. And another, with his faux-British accent and three-piece suit, just glared at me in the hallway. He informed me, with a sniff, that I was disturbing the only peace and quiet he’d had in thirty years, which Mother Nature had finally delivered to him through a plague, and which he thoroughly intended to enjoy. He may have screamed “Interloper!” too.

Man-lai Liang, the former model turned event producer, is still here; so is Tony Notarberardino, the photographer whose brilliant collection of Chelsea Hotel portraits of residents, guest and staff capture the spirit of the building, in a mesmeric, otherworldly way. There’s the Rips family—a writer/lawyer father, an actress/model mother, and a daughter who wrote a book, Trying to Float, Coming of Age in the Chelsea Hotel, when she was only 17; Michelle Zalopany, whose rich charcoal drawings are like living photographs of the past; Rita Barros, the Portugese photographer, who’s decorated the outside door of her flat on the tenth floor, making it an illuminated, ever-expanding art installation.

And then there is my father, George Chemeche, an 87 year old, Iraqi-Israeli artist and author; according to him, he took the taxi from JFK to the Hotel and never left. Our flat is on the fourth floor. My bedroom has an ensuite bathroom. The bathroom is made of glass. Father built it to illuminate the whole flat—like an enormous lantern—through the rippled glass bricks that make up its walls. Nevermind that anyone hoping to use the loo will be put on display for all to see.

My father seems impervious to my worries, waving away my anxious emails full of queries and anxiety over his safety. He pores over the pages of his latest book, Art that Bleeds Black. And every day, my father sends me a new poem, pithy comment, or philosophical thought. He’s a poet, too. Like Merle, Gerald, Susanne and Martine, he is just getting on with it.