I’m 24 and haven’t known a time when journalism was not in a raging struggle to survive. I was a teenager when Buzzfeed, Vice News and other digital-first outlets, backed by venture capitalists, attempted to revive the industry online. Media companies were hoping to master the algorithms of Facebook and Google for a narrowing share of ad revenue.

After graduating with a degree in media in 2017, I interviewed for a “real-time reporting” job at a local newspaper, and the writers there told me I’d be doing honorable work. By that time traditional outlets like these, hungry for readers, had taken up a new survival strategy in the form of quick-hit, sensationalistic stories. But later that day I spoke to a number of staffers at the paper, and most shared an eerily similar message. They told me the stories I’d churn out—aggregated summaries of trending topics, basically—would help pay the wages of more experienced people in the newsroom, so that they could create meaningful investigative work. My own work would require no original reporting and no face-to-face conversations with anyone (no time for that!). Instead, my stories would act as a “funnel,” the theory went. Someone would be tempted by the clickbait and find herself subscribing for more content.

I did my best to show that I was interested, desperate for any position that could provide professional experience. But I think they could see my heart wasn’t really in it, and I didn’t get the job. The paper’s parent company filed for bankruptcy earlier this year (though not only because they didn’t hire me).

Feeling isolated in my hometown of Raleigh with few resources or professional connections, I decided that if I wanted a job in journalism—and not one centered around the industrial process of writing clickbait—I’d have to go to graduate school. More and more young journalists are taking this route as they vie for a shrinking number of jobs. Many, like me, are willing to accrue tens of thousands of dollars of debt in the hope that new contacts and skills can provide a meaningful pathway into the industry.

I was willing to enter the fray in this uncertain media landscape because I was after something intangible. I’d often spend my evenings at the local Barnes and Noble, reading through a stack of magazines in a quiet corner, passionately moved by the hum of reality translated into words. Those corners of the bookstore were holy places to me. I read articles that made global, systemic issues feel vital, personal, something I could be—no, something I already was—a part of. Through them, I learned and felt how one’s life is inextricably bound to all others, and I wanted to spend a career chasing that all-encompassing, oceanic feeling—sharing stories, with reverence both to readers, and to the people who’d told them to me.

Over the past several months, I’ve been working on an audio documentary about fans who sent an album around the world to honor their favorite musician, Scottish singer and songwriter Scott Hutchison, who took his own life two years ago.

Since I’m not able to report in-person, I’ve been speaking to sources via video chat from a tangle of microphones, cords and headphones. I need these tools to produce clean recordings—my best attempt at mimicking the production of an audio studio. But there are countless opportunities for things to go wrong. The internet cuts out, or the person I’m talking to runs out of recording space on his iPad. Or there’s a lag, and I hear my own voice, echoing back to me in an endless loop.

With no possibility of conducting ordinary interviews face-to-face, speaking to someone across the world suddenly became equivalent to talking with a next-door neighbor. I’d learned a bit about remote recording techniques this semester as a master’s student at the Newmark Graduate School of Journalism in New York. When our in-person classes went online as a result of the pandemic, my audio instructor insisted we could use the situation as an opportunity to think globally.

So I chose a subject with an international scope and spoke to people from Sunnyside, California, Baltimore, Maryland and Worcester, a city in the U.K. I was running on a shoestring budget and recording from the closet of my childhood bedroom in North Carolina, squashing between old button-downs and dress pants to create a makeshift studio.

It’s hard to show that you’re really listening to someone when you can’t be in the same space together. Through the pixelated flatness of a Zoom call, it’s impossible to catch the slanted smile or the gleam in the eye that would ordinarily complete the meaning of someone’s words. Voices grow distorted and metallic through the compression of my laptop’s digital recorder.

But music provides a rare immediacy and connection that erodes barriers, as it did when I spoke with Fran Levitt-Higgins, a fan who’d eventually become close friends with Hutchison.

The idea that all of us can make as many changes as anyone on the planet, she told me, gave her hope. Hutchison’s willingness to be honest about suffering from depression was rare, and meaningful to a lot of people, I suggested.

“Hearing that message of: ‘I really have thought of taking my own life, but maybe I’ll just put that off, and if I just keep putting it off, I’m gonna be okay’—That has always been the strongest thing,” Fran replied. “That’s always brought me back to the music.”

In the middle of March, as University administrators scrambled to set up infrastructure for online classes, and students got used to working from home, an ideological battle around the role of student journalists was brewing. Some instructors argued that many of us are already working journalists, and that the school should support students making the tough decision to conduct in-person reporting when there are no alternatives. Others thought the university should set an example for journalism schools across the country by forbidding reporting in the field. Even professional journalists have an obligation not to spread the virus with unnecessary reporting projects, they argued.

Like all decisions during this pandemic, it’s impossible to weigh exactly the risks of in-person reporting versus the consequences of not reporting on a given story. My school enacted a policy that reflected the majority of professors’ opinions: All in-person reporting was banned indefinitely. But even with the new regulations in place, there was some wiggle room. Were the photographers among us allowed to snap photos on our way to the grocery store during an emergency food run? Could we knock on our neighbors’ doors, since they technically lived “with” us? How might documentary and video students learn about filming in a studio or in the field, if their cameras were fixed solely on the world inside their own bedrooms?

In those early days, when a new world of isolation and unending interiors was so unfamiliar to us, coronavirus coverage felt inescapable. In one class, where we’d originally intended to write about the elderly community in New York, we abandoned our entire syllabus and started over. We’d now be building a site from scratch to follow the experiences of New Yorkers during the pandemic. My professor asked us to write a barrage of stories that first weekend for a new site, the Coronavirus Chronicles. That’s what a real newsroom would do, after all, he explained. But my partner and I had temporarily moved back to our hometown in North Carolina. The majority of students at my school had made similar decisions to leave the city. So reporting on the daily lives of New Yorkers became a peculiar challenge for many of us.

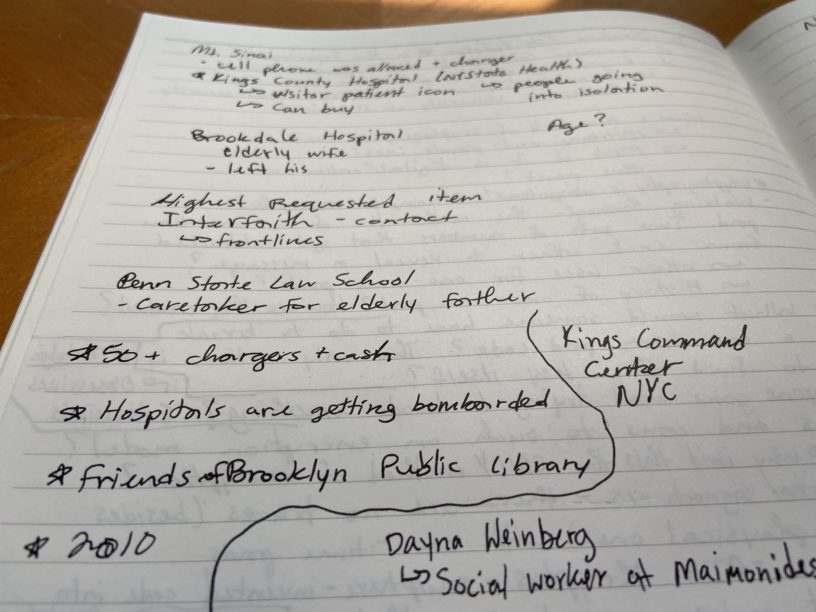

I wrote about Nailah Manns, a woman in Bedford-Stuyvesant who’d been collecting phone chargers for coronavirus victims: Many had long been quarantined in the hospital without chargers, leaving them with no way to get in touch with their families. Siloed myself at my parents’ house, I spoke to Manns over the phone. From five hundred miles away, I could get little sense of how things were for her on the ground. I didn’t know the best questions to ask, and I fumbled through the interview.

My program arranged a meeting last month with students from a journalism school in Paris. When I joined the group, I was greeted by a vast grid of tiny faces, maybe 50 students and professors in total. Participants occasionally got up from their seats to grab a coffee or to adjust their lighting or to quiet the kids. We compared what life was like in each country, and discussed how our respective reporting projects had changed. It had been routine for the French students to travel abroad for their magazine reporting projects each year. This time, they were staying home.

Professors from both schools asked whether students might discover that they actually preferred online classes over in-person ones. It was a lovely opportunity in some ways, no? There’d be no more sweaty commute on the train and no need to get up early to prepare for classes; we could log in mere minutes after waking up. And now, at least, we’d be prepared for a future where most reporting will be done online. It’s just that we’ve speeded up the timeline a little.

Then we conducted a poll, which revealed that no, the vast majority of us ached to be in class face-to-face. Some of us had even considered dropping out or postponing our final semester at school. We feared that an online education wouldn’t prepare us for the on-the-ground reporting experiences we’d need to secure a job in journalism. It was already going to be hard enough to do that in normal circumstances. The bleaker-than-ever job market, and the fact that it remains difficult for young journalists to receive basic healthcare, or to make a living wage, compounded our discontent.

In 2019, I took a plane to New York and attended an open house at the Newmark J-School, built in the former headquarters of the New York Herald Tribune and less than a block away from the New York Times building in Times Square. The admissions directors led us into an open space in the center of the building that acts as a newsroom for students. There were long rows of tables surrounded by mounted TVs broadcasting CNN and Al Jazeera and NY1. On a table near the front of the room, copies of the nation’s daily newspapers were stacked alongside local, student-run publications. I noticed old-school landline phones laid out on each table — the kind I envision some chain-smoking muckraker using in the 70s. I had no idea how to work them, but I liked that they were there.

features a character who sells the New York Herald Tribune on the streets of Paris.

The paper was known for its internationalist perspective.

I was especially drawn to the school’s core tenets: That you can’t know about a place until you go there, and that being a good listener is a journalist’s most useful skill and greatest challenge. I liked their scrappy, practical spirit, and their insistence that classic reporting techniques should be at the center of one’s studies. So I enrolled.

I took an introductory “Craft of Journalism” class in which each student is assigned a particular neighborhood to write about for the semester. The course orients newcomers to the city, while simultaneously immersing them in the daily grind of beat reporting. Our introductory assignment involved approaching strangers and asking them about what changes they’d like to see in their neighborhood. I wandered around the park, wielding my notepad like some kind of salesman, and wearing my school ID for added confidence. One guy could just not stop laughing about it. “What changes would you like to see in your neighborhood?” He thought it was the silliest question.

In my assigned district, Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant, a lot of people are quite happy with their neighborhood and are desperately fighting for it not to change, as the city succumbs to rapid gentrification. I think this was partly the purpose of the assignment: to be put in an uncomfortable position and learn that your questions are irrelevant, that you are entirely missing the point. Journalists miss the point a lot, especially when they’re reporting on a community that is not their own. The only way to do better is to go there and listen, and make mistakes, and ask, “What am I getting wrong?” I am still learning how to do that.

As the end of the semester drew near, deadlines streamed in, but I had no way of gauging whether I’d been producing anything worthwhile. My audio documentary class got together one final time to listen to the projects we had worked on that semester, and I scanned the screen at all of my classmates, scattered now across the country. My instructor suggested that each of us lower our lights, place a candle on our desks and have a warm cup of tea on hand. After a grueling semester, it was time to relax and reflect on our work. But I worried that our documentaries might reflect the cold distance of having never really met the people we’d been covering.

Instead, each documentary was brimming with humanity. One of my classmates created an audio piece about restaurant servers struggling through the coronavirus shutdown, and the funds that have been set up to support them. She learned that servers who had savings or secondary streams of income had opted to distribute their share of donations to those who were struggling the most, especially undocumented folks who had no way of securing unemployment benefits. Another colleague pieced together user-submitted audio clips of people’s mundane, daily routines during the pandemic. I listened and laughed as a dog slurped into a water bowl and excitedly jingled its collar before a walk. I teared up when a mom sang on the piano with her daughter, who was evidently still too young to form words, but not too young to sing her heart out in spirited but indecipherable wails. Concerned neighbors left voicemails to check on the other tenants in their buildings, and friends called with happy birthday wishes. Humans could still be human, even when they couldn’t be together.

All of our documentaries are like time capsules, reminders of what it was like for all of us to be sequestered and separated. Maybe in the future, people can use them to learn about this surreal moment in history. The country’s unending traumas—the coronavirus and racism and police brutality and every other problem—aren’t going anywhere. But we can still try to communicate with people who can teach us about their lives, despite a system that seems to want to see us fail.

I’m sure I missed out on some things this semester, but that’s okay. I do want to start meeting people again. I want to hover over the East River on the M train with printouts of readings for class and look out onto the glistening skyscrapers that stretch to the horizon. I want to sit down with someone over coffee and ask them a thousand simple, dumb questions, until I begin to understand.