About 70% of the world’s languages incorporate tonal distinctions. In Yorùbá, tonal differences distinguish the word owó (money) from òwò (business) and ówo (a boil); ọwọ́ (hands), ọwọ̀ (broom) and ọ̀wọ̀ (respect). Even the variants between dialects in languages like Yorùbá and Igbo have made agreement on a unified orthography a real problem. As I wrote in 2018, dozens of tonal distinctions may alter the meaning of a single innocuous-looking Yorùbá sentence, e.g. “Baba mi ni oko nla”—from “Sorghum shook inside the big car” (bàbà mì ní ọkọ̀ ńlá) to “My father has a big penis” (bàbá mi ní okó ńlá) to “My bronze is a big farm” (bàbà mi ni oko ńlá).

Yorùbá and Igbo have evolved over the years, with various twists and turns affecting usage both spoken and written. And since Bishop Àjàyí Crowther wrote the classic texts, Vocabulary of Yorùbá (1843), Isoama-Ibo Primer (1857), and Vocabulary of the Ibo Language (1882), disputes regarding the orthography of these languages—attempts to agree on how, exactly, they should be written—have continued to rage in academic, literary, and colloquial circles. It is not uncommon today to find competent speakers of both Yorùbá and Igbo who don’t know how to tone-mark written words, so that the end result appears like a standard English text, leaving room for plenty of ambiguity.

Compulsory Nigerian language education was dropped from high school syllabi in 2015. But aside from the end of the formal secondary-school educational requirement, the evolving adoption of these languages seems to have been hampered by the confusion occasioned by diacritics. People commonly complain that figuring out the implications of each mark on the letters slows down their reading. Another obstacle to comprehension is that the Latin letters used in English, though they are identical to those modified for use in Nigerian languages, represent different sounds. The /e/ sound is more of the sound in ‘pain’ than the sound in ‘pen’ (which would be /ẹ/), for example.

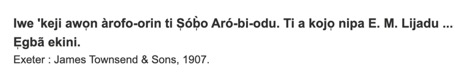

Unicode was designed to facilitate the digital rendering of languages by encoding scripts into uniquely identifiable computer codes. But because of its lack of precomposed characters for vowels requiring both the subdot [e.g. ẹ, ọ] and the tonal diacritic [e.g. ì, í, á, à, ò, ó, è, é], digital rendering of Yorùbá vowels that carry both [like ẹ̀, ẹ́, ọ̀, ọ́] often need to be overwritten with the second diacritic mark. This results in frequent font-related snafus on modern electronic platforms. Here’s an example from the British Library:

There should not be a diacritic on or under the letter ‘b’, an error caused by Unicode’s reluctance to incorporate secondary formatting.

Insufficient attention to African orthographies in the digital age has also ensured that only a few contemporary fonts can adequately render them—even if one successfully combines diacritics on letters and words, as I once discovered when I tried to change the font on my website.

[Popula’s fonts are no exception, for which we apologize—Ed.]

Something needed to be done.

Enter the Ńdébé Script: a writing system that addresses the tonal peculiarities of Nigerian languages, pleasing to the eye, which might carry the burden of our literary and academic aspirations.

Created by visual artist and software engineer Lotanna Igwe-Odunze, the Ńdébé script provides a suite of tools for cultural expansion through literature, calligraphy, and visual art.

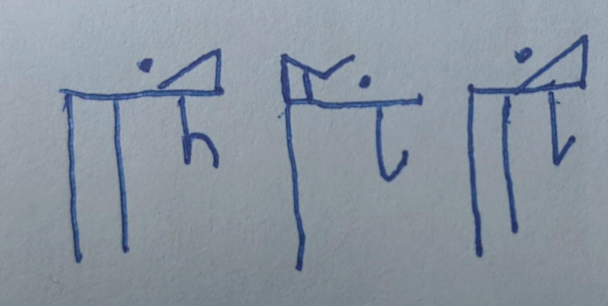

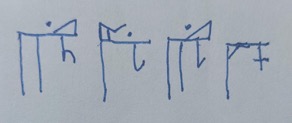

Having been exposed to other logographic scripts like Hangul and Devanagari, I found Ńdébé to be quite straightforward to learn. Consonants are the main stems of the script, while the vowels are appended to the tops of characters. Tone is accounted for with dots, and the visual direction of the vowel rendered in a manner not dissimilar to our current diacriticized Latin script. The high tone conveys climbing a hill; the low tone descends. Users can intuit from their own rising or falling voices which image best represents the appropriate vowel.

In addition Ńdébé supplies, for Igbo at least, an opportunity for different dialectal variations to find harmony, a problem that has bedeviled written Igbo for years. Where some dialects might write ‘to eat’ as n’eri and another one n’eli, Ńdébé provides the same character to represent both, obviating the problem completely. This is remarkable. And yet there is still another character that represents only the /l/ phoneme, which can be used in instances where no such dialectal variation exists. As a linguist, this brilliant logographic economy pleases me. But I’m still interested to see whether it is adopted, with no confusion, by those long accustomed to the old substitutions.

Vowels are separated into low, rising, and high categories, which are presumably the only tonal delineations in Igbo. The notable absence of a corresponding “falling” tone, I first thought, creates problems for adapting the script to a language like Yorùbá, where, for example, the ọ̀ in Báyọ̀ carries a “falling” rather than a “low” tone when the sound is properly rendered. But on a second look, I find that what is meant as “rising” here is actually the same as a “mid” tone in Yorùbá. Still, linguists interested in adapting Ńdébé for languages with different tonal patterns than Igbo’s, or with no tone at all, like Fulfulde, have plenty to work with. Igwe-Odunze, who has been working on this writing system for over ten years, has been clear that her original intention was to provide an Igbo script, calling Ńdébé her “gift to every Igbo person.”

ndebe.org

There are other projects looking to achieve similar goals. The New Nsibidi, which repurposes an old pictographic writing style common in the shrines and secret societies of the Efik and Ibibio people of Southern Nigeria, is one of these. Examples of the original Nsibidi survive on shrine walls, pottery, in masquerade societies in Calabar, and even as far afield as Cuba. But a complete understanding of its internal logic has not survived. Nsibidi has remained an esoteric body of knowledge, used only for ritual and visual arts purposes. Recently, though, people have begun using its symbols in a new alphabet for writing Igbo. There are many YouTube pages teaching the skill.

Many have suggested returning to the earlier Arabic-based symbols in which the Yorùbá language was first written (a system something like the Katakana alphabet in Japan, which is also used to render “gairago,” foreign loan-words). This alphabet is called Ajami, from the Arabic root for “foreign,” but not much of it has survived, nor are there many scripts from which one can learn how the system works. And in late 2019, I heard about an invention called “the talking alphabet” that was suggested as a replacement for the current modified Latin script for Yorùbá. Still, no learning materials have been published, so it doesn’t seem to have developed beyond a web craze.

Writing My Name

In attempting to write my name—a Yorùbá name—in Ńdébé, I ran into a problem that I believe needs to be solved even for Igbo. My last name Túbọ̀sún can only be written as Tú-bọ̀-sú-n in Ńdébé, where the /n/ is treated as a stand-alone consonant, though it’s there only to show that the -un is nasalised. Ńdébé is syllabary—like Hangul, and again, Japanese—meaning that every segment of writing you see represents a spoken syllable, so my last name should, at least visually, be in three segments. When the last n is written as a standalone syllable making a total of four, it messes with a well-crafted system. Currently in Ńdébé, only the u vowel is accounted for, and not its nasal element. The easy solution would be to include a un vowel, which (contrary to how it looks in the Latin alphabet) is not two letters at all, but one sound.

But then Ńdébé doesn’t pretend to be a sound-based script, though its impressive attention to the rendering of tone makes it seem like one. Its main focus is the syllable, much like Hangul or perhaps other scripts like Devanagari. As a writing system, it is easy and logical to learn and easy to teach to either humans or to computers.

Logic is the language of computer systems, and if a script is easy to read and write, then computers can learn it. People who have written Igbo with the current Latin script have often done so without diacritics, claiming that diacritics make the language either difficult to learn or harder to read—the same thing one hears from writers of Yorùbá who are not competent in the written language. Consequently, novice learners have an additional hurdle to clear in learning how to pronounce Igbo. Ńdébé’s attention to a logical, and most importantly visual system of marking tone promises an improvement on the current system.

I created a speech synthesizer for Yorùbá at TTSYoruba.com (the first for the language), which benefited from the logical nature of the current tonal marking system, making it easy to teach to computers.

In a paper I recently submitted documenting the process behind the TTSYoruba synthesizer, I lamented that the diacritical logic of Yorùbá, which had helped make my work easier, would make it harder to make a similar synthesizer for Igbo, a language in which people have abandoned diacritics entirely. Igwe-Odunze’s invention makes me revisit that premature declaration. The low tones in Ńdébé have the visual representation of descending, while the high tones have the visual representation of ascending. The “rising” tones combine both, so whoever looks at the text, machine or human, can literally see the correct pronunciation. That changes everything.

The only drawback remaining is a human one: writers will still need to know whether they need a high, low, or “rising” tone, just as they do now. But the visual representation of the diacritics—pleasant to the eye, logographic, and directional—might help make the learning easier. What it already does for me, and for any new reader of Igbo, is make the reading easier. And if I, a non-Igbo-native speaker, can read Igbo with the appropriate tone by just taking in an Ńdébé text, then so can the computer. Hello, Igbo text-to-speech, voice assistant, speech recognition, etc.

I spoke earlier about my difficulty in using Ńdébé to write in Yorùbá. This is not a permanent stricture. Igbo Nigerians reading the imperfect Yorùbá word via Ńdébé will presumably have a good idea of what Yorùbá name/expression is intended. But when the language is encoded to a speech synthesizer, for instance, and a machine is asked to pronounce it, the result will sound more like Igbo than a Yorùbá word. But this is hardly a deficiency that cannot easily be mitigated by a pan-Nigerian addendum to the script, should the need arise. After all, we have modified the Latin script over the years to our needs, and no heaven has fallen.

The Impact for the Future

I have spoken so far about the linguistic characteristics, advances, and limitations of the new script, which are necessary for its expansion into more formal literacy, literary and technology spaces. But where I think the script most succeeds is in its opening of a new vista for the revitalization of Igbo as a written language both on the page and on the web, for literacy, and for culture. Visual allure is an underrated aspect of the potential survival of a script. Old Nsibidi has endured because of its transmutation into the ritual and visual arts space (See: Black Panther), but inscrutability is not always a virtue. As a lifelong advocate for multilingualism in Nigerian public spaces, I can see Ńdébé being used along with English or other language texts on signposts throughout the country. That is an assertive statement to counter what currently exists as the closest gesture to bilingualism: Mandarin signs near refineries in Lagos.

I want to see Ńdébé on signboards, computer decals, book covers, art installations, comics, scriptures, and yes, computer fonts (no excuses now, Unicode), textbooks, government documents, Nollywood films and literature. I want to see it adapted and refined. As a native invention with the possibility of embodying the pride and possibility of a people, the script is a triumph. As a new vehicle for Igbo literacy, calligraphy, with an element of cool, even more so.

Lotanna Igwe-Odunze does not call herself a linguist—not having studied the subject formally—but the logic, ingenuity and tenacity she has used as the basis of her invention is no different from that of King Sejong, who first encoded Korean in Hangul in 1443, or of David J. Peterson, who created Dothraki and Valyrian for the Game of Thrones franchise, or other conlangers, who continue to expand our imagination with invented languages.

Even the creative naming is to be praised. Ńdébé is coined from “ide”, which is the Igbo verb meaning “to write”, added to the “n” morpheme for “continue to.” So more than inventing a writing script, there is also an interest in lexicography that is obvious from the passion and record of Igwe-Odunze’s work.

And now that Ńdébé has been shown to the world, I’m quite excited about the dynamism with which the script will grow, through usage, into more things of wonder.