What with Blade Runner on everyone’s mind in recent days (“cyberpunk” and whatnot), I revisited my review of the movie and was chilled to the bone at how this story reverberates at the end of the year 2020. Yikes on bikes.

Don’t read this if you haven’t seen the movie and maybe don’t read it ever, because the message of Blade Runner 2049 is the wisdom of embracing and living in mystery; the same lesson we learn from the poet John Shade, the man at the center of Vladimir Nabokov’s 1962 novel Pale Fire, the movie’s touchstone.

References to the novel crop up repeatedly, but not in the usual blockbuster movie manner of hauling in pseudo-literary references in order to lend a sensation of depth. The near-death experience in which Shade saw the oft-referenced “tall white fountain,” and the lesson learned from his investigations of it, echo the experiences of the replicant Joe, Ryan Gosling’s character in the film, in a heart-stoppingly resonant way.

Much is made of Joe’s name. The name by which he is known to the authorities, his bosses, and his society is depersonalized, a serial number, but one he loves gives him his real name, a name he scarcely dares to use. There are a lot of references to wanting to be a “real boy.” The theme of a heroic little boy—Peter, from “Peter and the Wolf” — plays repeatedly, too. Joe is a robot who wants to be real, but he can’t be sure what that desire is, or if the desire itself is real, or what it means or might mean.

(It’s been noted too that Joe’s name recalls that of Josef K. from The Trial, and that seems intentional, too—this Joe being likewise in mortal danger and trapped in a cruel, senseless society.)

Replicants in both of the Blade Runner films are allegories of human beings. Like them, we are finely-made machines with almost incredible capabilities; like them, we have incept dates and are eventually “retired.” Like them we cling to existence tenaciously, lovingly, in confusion, panic and hope—hope that there might be some reason why this is all happening, and still more than that: Hope that there might be, and even that each of us might someday learn there really was, a worthwhile reason for our own tiny part in it all along. The first film was about the unstoppable desire for life, and how even if you were to struggle so hard that you could finally face God and ask for more, you will never have all you want. The ontological question, if you like. The sequel is concerned with the epistemological one, and is far subtler; it’s about the latter part, the impossible search for an explanation.

Within the novel, the 999-line poem “Pale Fire” is the autobiographical story (told in technicolor iambic pentameter of the most spine-chillingly exquisite quality, and you better read it, if you haven’t) of John Shade’s life, the central fact of which is that his beloved daughter, Hazel, drowned herself at age 23. What does your life mean, what can it mean, when something like this has happened? The poem is addressed to his wife Sybil, and it starts like this:

I was the shadow of the waxwing slain By the false azure in the windowpane; I was the smudge of ashen fluff — and I Lived on, flew on, in the reflected sky.

Shade (n.b. the friendly Nabokovian love of obvious puns) is dead already; he died when his daughter died; he’d been flying toward a false sky, unaware that something as completely unseen and unpredictable and obvious as a pane of glass would kill him in midflight — and yet somehow he kept living. His old self left behind no more than “a smudge of ashen fluff” but on he flew, inexplicably, through a world both real and not, substanceless, sundered from himself. His life!—all the different things happen, experiences they had together, things he sees, beautiful things, curious things—his whole life, or shadow of a life.

And then one day Shade is giving a lecture and collapses with a heart attack, and within it, a vision.

Cells interlinked within cells interlinked Within one stem. And, dreadfully distinct Against the dark, a tall white fountain played.

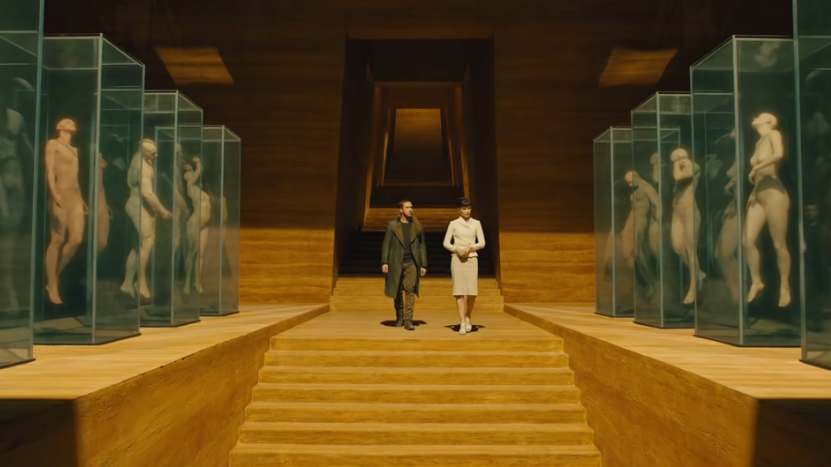

These lines recur in Blade Runner 2049 multiple times as a sort of test of Joe’s sanity, like a car diagnostic. Hesitations, it seems, or evidence of questioning, indicate a malfunction in the machine. Joe too is wondering, even though he isn’t supposed to, what everything is for—what he himself is for. For Joe, the fountain is the little wooden horse he remembers (or does he?) from his childhood in an orphanage. The curiosity he dares himself to follow to its conclusion leads him to this totem, and finally to Deckard—also revealed to have been a replicant in the first film, as many suspected. (There is doubt on this point, but I’m convinced it’s resolved in this film.) There is a rapport between the two that may indicate an answer to Joe’s question of why, why he is important, “special” as his lover says. Why he exists at all: it seems there may be a reason.

The truth is something far stranger, vastly more complicated and more impossible, just as it was for John Shade.

When Shade discovers that his great epiphany regarding the white fountain—the incredible explanation he stumbled on for what lies, surely and in fact, beyond death—was only the foolish result of a misprint in a magazine, he drives home in confusion.

I mused as I drove homeward: take the hint

And stop investigating my abyss?

But all at once it dawned on me that this

Was the real point, the contrapuntal theme;

Just this: not text, but texture; not the dream

But topsy-turvical coincidence,

Not flimsy nonsense, but a web of sense.

Yes! It sufficed that I in life could find

Some kind of link and bobolink, some kind

Or correlated pattern in the game,

Plexed artistry, and something of the same

Pleasure in it as they who played it found.

(“They who played it” I’ve always taken to mean the Greek gods, or beings like them; capricious, weirdly playful, mixing beneficence and malevolence in the same topsy-turvical way Shade suggests.)

The answer, for Shade as for Joe, is the hardest one, the one we’re living every day: To live, to keep flying, even through the unreal. This really is a movie for our times.

I’ll always imagine Joe pondering these lines, lying back on the stairs as the snow falls. (We know he’s read the book.)

This is a good movie but it’s not a Popula Film Club selection, because it is available to stream only through corporate channels, alas. We suggest buying it on DVD.