The first thing I noticed about my father’s new house, when I first visited in 2003, was its atmosphere of seclusion: dark, towering fir trees in the front yard dwarfed the house, and forbidding wooden fences enclosed the property on three sides. Behind them, 14-foot tall cedar hedges formed a final dense and forbidding barrier.

He’d flattered me by asking for my advice a few weeks before: Should he buy the spacious bungalow he’d found in the suburbs, with all its amenities—a pool!—or the inner-city duplex where I’d grown up, in order to remodel it into a family home? He had just gotten remarried, and would be buying the new place to welcome his new wife and her two young daughters. I was touched that he’d included me in this decision.

I was in my early twenties then, living the life of a hungry musician.

“You deserve a pool, Dad,” I said.

Not long after, he called to let me know that the suburban house was his, and invited me to visit. He picked me up at the bus station. As we drove through the quiet postwar suburb with sturdy bungalows set back from the curb and no sidewalks, I felt a twinge of jealousy that his new family would get to enjoy living here, and that I’d missed out on these suburban comforts.

Inside, the house was clean and well-maintained, if a little stuffy. My dad pointed out renovations he intended to make: removing the carpet from the stairs to the basement, tearing out an old wooden cabinet. I looked inside the glassed-in cabinet and noticed, on faded red felt, the sun-bleached outline of what looked like a pistol. “Yeah,” said my dad, with a mischievous grin. “Check this out.”

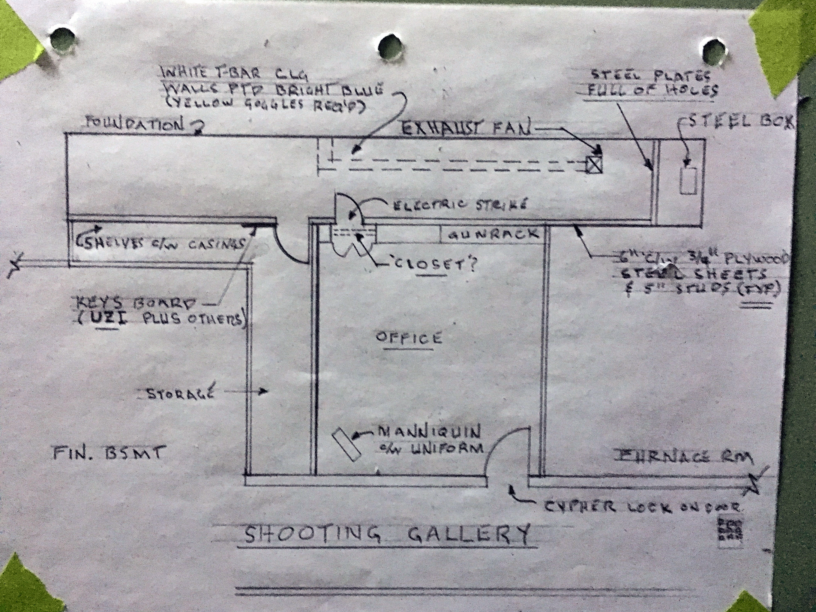

He led me down the basement stairs to a wood-paneled door, punched numbers into the cipher lock above the knob. The door creaked open and he flicked on the harsh fluorescent lights.

The wood-paneled room was about twelve feet square, with a low ceiling and an ominous vibe; it was easy to imagine someone being held captive there. Against two of the walls were cabinets similar to the one upstairs, glassed-in, lined in red felt, empty now, but bearing the outlines of objects visible on the fabric: rifles, handguns, unrecognizable shapes.

There was a small closet at the back of the room; strangely, the inside was painted a bright sky-blue. My dad reached to the ceiling, pressed a hidden button and then pushed open the back wall of the closet, into an inky blackness—a secret passage.

“Oh my God,” I said.

“Yeah,” he replied, stepping carefully into the black. A few moments later a light clicked on, I followed, and found myself in an entirely different world.

The walls of the concrete walkway were too narrow to extend my arms, and painted the same weird sky-blue as the closet. The corridor extended thirty feet or so to my right, and at the end of it, in a cut-out of the wall, was a steel plate shredded and warped by gunfire.

Behind me, at the far end of the corridor, I found my dad digging through a large coffee can: it was stuffed to the brim with spent bullet casings—9 millimeter, .45 caliber, .30-30 rifle rounds.

“This was his shooting range,” he said.

A second narrow passage, this one unlit and dank, with wood-frame walls rather than bright blue concrete, extended perpendicularly from the shooting range. The claustrophobic space instantly conjured the feeling of a trench in a war zone. A third corridor stretched away to our right, into some other darkness. It was a fantasy stage set of warfare.

The wooden shelves near my face bore a series of empty key hooks, each with a faded masking-tape label above it. One read ”Handcuffs,” and another, “Uzi.”

“What the fuck,” I said.

That’s when my dad told me the previous owner had been a dedicated Nazi soldier.

Thoroughly creeped out, I followed my dad back out of the secret lair and into the present day. We shut the trick wall behind us and turned out the light as we left the little wood-paneled room, closing the cipher lock door. I didn’t know it then, but I would soon find myself back in that basement, facing a darkness of my own.

A couple years after my dad showed me the Nazi lair, on the night of my 25th birthday, I made a fateful and terrible decision. Playing a concert at a Montreal club, dazzled by strobelights and machine-generated smoke, I leapt off the stage into blackness. When I came to, I was flat on my back and in excruciating pain. In the ambulance I begged paramedics to just cut my leg off, the source of my agony. We got to the hospital, a surgeon slapped a Fentanyl patch on me and I drifted away.

I awoke to learn there was a permanent steel rod in my leg. I had catastrophically broken my left femur, the doctors explained, and dislocated my hip; I would need to learn to walk all over again.

A few days later I called my dad and asked if I could come home. It would be a full house, with me joining him, his wife and her two daughters in the three-bedroom bungalow. He set me up in the basement, chilly but comfortable. In the Nazi office, everything was just as it had been years before.

Exhausted and depressed at the prospect of a year-long recovery, I sank into a routine of pain medication and half-hearted exercise. The days stretched into weeks; I would close myself in the Nazi office, with its gunshadows and off-the-grid vibes, and one-foot hop my way through the closet into the shooting range to smoke. The Nazi’s presence was strong, or so it seemed: I could sense the humiliation and rage imbued in the walls of the lair; a projection, perhaps, of my own humiliation at having injured myself so badly through my own hubris.

You don’t build a place like that to forget. You build it to remember, to relive—maybe even to dream. The lair was like a chamber hidden deep in someone’s mind. No ghost could live there, because the place felt so thoroughly lived in; it had the well-worn feel of a living room where many hours had been passed. Not happy hours—despairing, lost hours, ripped through with blasts from weapons of war. A place where the Nazi could pretend, maybe could even believe, he still had power, worlds away from the progressive and bewildering reality he must have found in postwar Canada.

Canada declared war on Germany in September 1939, after a German torpedo destroyed a passenger ship, killing a woman from Quebec: the only time Canada has ever declared war on its own.

My dad’s father fought the Axis powers as part of a Canadian Army artillery squad: his unit rained shells down on the fascists of Italy and cleaned out straggling occupiers in France, Belgium and Holland. My grandfather returned home carrying the deep trauma that so many veterans bear—he never talked about his experiences of the war. But victory came, in the end. Canadians still receive thousands of tulips from the Dutch every year in thanks and remembrance for our contribution to liberating their country and crushing the Third Reich.

During the war, Canada established a series of internment camps across the country to house captured POWs from the combat fields of Europe and Africa, along with Canadian citizens of German, Japanese and Italian descent. Canadian POW camps categorized Nazi prisoners using a color code to identify their degree of loyalty to the regime: white was reserved for unwilling collaborators, black was for hard-core Nazis, grey for those somewhere in the middle.

After the war ended, denazification and repatriation programs were put in place for the prisoners. But an intense focus by authorities on boosting immigration after the war resulted in a lukewarm approach to weeding out the Nazis who had escaped the collapsing regime. Between 1945 and 1955, 1.5 million immigrants of innumerable nationalities came to Canada; historians estimate between 2000 and 5000 of those arrivals were secret Nazis. (This was in addition to the Nazis invited deliberately by Americans and Canadians.)

The Canadian government’s tepid attempts to pursue war criminals had ended by 1948, when the Allies decided that efforts should focus on “discouraging future generations” rather than prosecuting escaped Nazis, or in the words of the British Commonwealth Relations Office, “meting out retribution to every guilty individual.” Later attempts to prosecute Nazis hiding in Canada were unsuccessful.

So it was that thousands of Nazis, who had been fighting the Allied advance a few years before, found themselves in a prospering Canada, where they could reinvent themselves and start anew—or simply paper over who they had been and what they had done and settle into a new life, some of them full of secrets and hatred swirling like magma below the surface of a burgeoning suburbia.

We don’t know whether the Nazi in the basement was a freed prisoner of war, an escaped war criminal, or one of the prized Nazis invited by Canada to live and work here. But I think it’s clear he was no white-or-grey German soldier; the complex of tunnels, the lovingly-displayed memorabilia and the penchant for discharging high-powered weapons in secret paint a picture of a dyed-in-the-wool Nazi who kept the faith, in his bunker, right up until the end.

One night when I was living in my dad’s basement, I took a little too much dilaudid and made the mistake of drinking a beer. As I hobbled out of the shooting range, my vision went fuzzy and the ground rushed up at me. I hit the ground, a breath away from passing out, and held my head in my hands until I regained my faculties. The next morning, I awoke in my bed adjacent to the Nazi lair, sat up and felt something alien on my leg. I looked closer and saw a ripening bedsore. I was wasting away.

I jumped up, horrified, finally filled with the desperation and resolve I needed. From that day forward I did my physiotherapy religiously, and stopped taking pain meds, determined to get my life back. Six weeks later I was back in Montreal, walking with a cane, writing the music that would result in the most success I ever enjoyed as a musician: I toured Belgium and Holland, where I contemplated the fog-shrouded hills of Liege and marveled at the shimmering glass edifices of Rotterdam, built atop the pulverized remains of a city almost entirely destroyed by fascists.

While writing this story I called my dad to talk about the lair. On his first visit as a prospective buyer, he said, the seller had told him of the major cleanup they’d done on the place; there had been a mannequin dressed in full Nazi uniform in the office. Two hundred and eighty-eight guns were removed, including a 19th-century cavalry revolver from the days of the American-Indian Wars and an ancient flintlock pistol, rumored to have been owned by an honest-to-God pirate, centuries ago.

And there was also plenty of other “weird shit,” apparently.

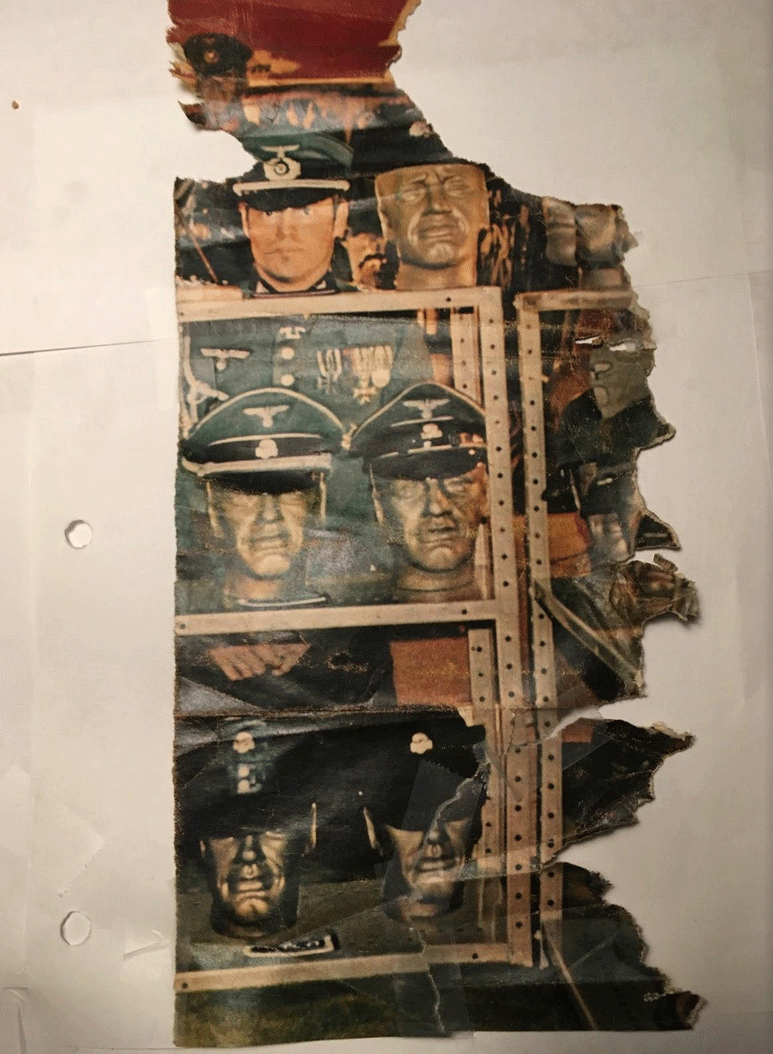

“He had cut out pictures of women, from Playboy, you know, and pasted them all over the ductwork,” my dad said. “I painted over them. I also found pictures from magazines showing mannequin heads with different Nazi hats on them,” he told me. As we spoke he dug around in the basement and found one of those.

“White supremacists, Nazi shit, that’ll never go away,” my dad observed with contempt. “There are probably more of them out there now than there were after the war.”

My grandfather’s picture hangs in the entrance of my father’s house, his young man’s grin revealing the pride and confidence of one engaged in the heroic act of fighting Nazis. His medals shine below his picture. The Nazi lair has been gutted and transformed into a jam room, where my dad plays his bass guitar through a heavy black amplifier. I like to think that this conquering of a last splinter of Nazi territory gives my grandfather an ongoing satisfaction, wherever he is now.