Reluctant to start on my PhD in a pandemic-stricken US, I recently found myself searching for a viable way to stay in Beijing, where I have studied and worked for the past five years. I was luckier than most: Chinese-Americans can apply for family visas, freeing us from the nail-biting process of finding a company that will sponsor us for work permits. But I still needed to pay rent. A former teacher at Tsinghua University gave me a lead: CET, a Chinese language program for American college students, had recently expanded its offerings. Partnering with American universities, they now offered classes that incoming Chinese international students, stuck back home, could take in Beijing.

English teachers here get paid upwards of $100 an hour to minister to well-behaved, affluent high schoolers. Problem solved.

My class was called “Communication.” Every Wednesday at 6:00 pm, I’d make the commute to Capital Normal University, flash my face at the biometric cameras outside the gate, and be waved in; security tightened and loosened depending on the rate of covid infections. I’d teach until 9:00 pm, and then, exhausted, head out across campus, where loudspeakers blared news and cheery propaganda. My students needed permission slips to leave campus at all, and many invented maladies in order to arrange for a brief escape.

But they didn’t have it so bad. The soft-spoken, guarded twenty-somethings I’d gone to grad school with at Beijing Normal were some of the country’s poorest and most talented applicants, people in whom whole villages placed all their hopes. The kids at Capital Normal wore sneakers that looked more expensive than my laptop, and loudly giggled to each other as I tried to introduce myself.

In my haste to gain their respect, I’m afraid I offended some. Racial hierarchies work even more nakedly in China than in the U.S., and an English teacher with an Asian face is automatically assumed to be less competent. So I threw out my credentials the way you’d throw your wallet at a mugger. I told them that I hadn’t expected to be here, either—I was supposed to be in New Haven, Connecticut, reading lots of books, okay?

During ice-breakers, one student, Dustin, told us that he had two brothers and a sister; I mentioned glibly how rare three-person families were. Dustin began to explain that you could pay a fee to bypass the One Child Policy, and I cut him off with, “Yeah, okay, we get it.” For his first homework assignment, he revealed that he’d thought he was a single child until the age of ten, when a teacher accidentally divulged the truth, which his parents had provided during registration. He explained, in quiet, painstaking prose, how his mother had reluctantly confirmed the facts that night, and how he’d eventually had to meet his three half-siblings. Horrified, I never made another comment about his wealth again.

The standard syllabus at CET specified that students would “develop and hone skills in the various written formats most common in the information environment, including, email, formal and informal documents, PowerPoints, etc.” But there are only so many hours you can spend teaching young adults more tech-savvy than yourself how to write emails. One fellow teacher, an ex-surfer from South Africa, prepared electronic handouts that made me question whether we were even living in the same city. One read, “In 200 words, describe a person you love. What makes him/her special for you?”

It took two weeks of seeing my students’ eyes glaze over at the niceties of email signoffs for me to give up and start improvising. I began adding cultural content, like high-school English and American politics, into our lessons, subjects aligned with my own interests. The average Chinese parent—mine included—would likely find the material trifling and indulgent. But if my students really did make it to the States, cultural fluency would be much more valuable to them than even the most thorough grounding in PowerPoint.

The first new assignment I gave was to ask them to write personal essays. I wanted them to peel back the frail petals of their innermost selves and reveal whatever throbbing secrets they were keeping—within reason—and promised that I tried to do no less when I wrote. I would be lying if I said I didn’t feel some ethnographic excitement within myself.

Bill had been forced to turn down a very late offer from Kyoto University, where he wanted to study animation design, because he’d promised to go to his backup, Franklin and Marshall. Alaia had turned down an offer from NYU, fearing a high-stakes social scene—which was exactly what Kim, who’d been rejected, had longed for. Kaitlyn, my most outwardly cheerful student, wrote of the happiest moment of her childhood, the night she was hospitalized for a severe nosebleed; her parents, normally stern and indifferent, had been uncharacteristically caring. Sylvia’s fantasies of college life—this, after all, was college—had been frustrated upon arriving at her dorm in Capital Normal and hearing the sound of electric saws through the wall. Annie worried constantly if she’d made the right choice—the news of Trump’s policies targeting international students filled her with increasing consternation.

Confronted with their dilemmas, I found myself unable to say, Yes, it really has all gone to shit. I wanted to sugarcoat everything for them, as though they were my nieces and nephews. I told Bill that there were plenty of animation enthusiasts in the States, though I suspected that many were poseurs; I comforted Alaia by telling her she’d made the right choice, even though Liberal Arts colleges like the one she was headed for often have tiny, stultifying social circles. New York is wonderful, I told Kim, without mentioning that it was being decimated by Covid. Confidently, I told Kaitlyn she’d work things out with her parents, even though I never had with my own. I didn’t have the heart to tell Annie that buyer’s remorse was only natural for people who’ve hitched their futures to a failing empire—that she was lucky to have committed just four years, and not a lifetime, like me.

Instead, I went in on their grammar—their dangling modifiers and fragments and run-ons—not just because I’m a hopeless pedant, but because people who look like me need to speak and write immaculately in the States in order to be taken seriously.

After personal essays, I assigned argumentative essays. Another high school tidbit—that a thesis should be provable and debatable (“grass is green” fulfills only the first condition, “the moon is made of cheese,” only the second)—proved surprisingly opaque for some of them. This illustrates the falsity of the cliché that Chinese students “can’t think”—they are experiencing, rather, an epistemic schism: in China, erudition and indirection are marks of brilliant rhetoric. Some of my students were steeped in this tradition: Cerella wrote long-winded essays with idioms translated from Chinese, “what sticks to cinnabar is red; what sticks to ink is black.” I tried to guide them into direct, five-paragraph essays—again, not because it’s the only “proper way to write,” but because it was the only way they’d get good grades in college.

Students who’d attended international school—expensive private academies attended by children of foreign nationals, like diplomats, and wealthy Mainlanders—had an easier time, but their points often surprised me. Gabe, an avowed Marxist and history buff, wrote that in China, “the feminist movement is off track,” actually pushing women further from equality. “Extreme feminism holds that marriage and reproduction both violate women’s rights, because they allow men to control women’s uteruses, and subjugate them as ‘tools of fertility’”; on the opposite side of the spectrum, he wrote, some so-called feminists “have created an evaluation system for men based on their social status and wealth… a form of social Darwinism and money worship.”

Sylvia, a fan of Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie, led the counterattack. During workshops, she quoted Gabe’s complaints about being made to “tolerate girls’ rude behavior, pay their bills, and mop the floor for them.” He was bringing up trivial instances of preferential treatment, and ignoring the lack of differential politics when it mattered. She brought up an infamous episode, early in the outbreak, when a number of female nurses were forced to shave their heads to “better protect themselves,” crying the whole time. Did he really think this was “equality”?

Harried, Gabe tried to explain that he objected only to feminists’ pursuit of priority over equality. I waited for someone to tell him that while flipping hierarchies was certainly a danger, such revenge-takers made up a minority of China’s feminist movement, in a country where even accusing someone of sexual abuse has resulted in the abuser suing the abused.

But Sylvia sat back and nodded. “Yes, okay, I can agree with that,” she said, with an arch smile. It wasn’t quite what I’d expected—in the States, Gabe wouldn’t have been given an inch of space to retreat—but it was something.

I told anyone I met that I was freelancing, and that I had a gig as a part time lecturer at a university—technically all true—and prayed they didn’t ask me what subject I taught. I found the idea of teaching English embarrassing. But I still found myself caring very much how my students fared; for them, this was freshman year.

About two-thirds of the way through class, I started polling them about topics they wanted to study, things that they thought would be useful. Slang was one of them.

Words have careers of their own, I began, explaining how OK began as Oll Korrect, a joke lampooning a misspelled 19th-century political banner, then slowly grew from password to byword across the centuries. Most slang words don’t make it so long; American slang, especially, tends to have a short lifespan. Today much of it is coined by young, non-white neologists, who sometimes react with dismay when their language is coopted across the country. The topic brought us into issues of race, authenticity, recognition and power.

“Questions or comments?” I asked. There was an ominous silence.

Kaitlyn spoke up. She was one of a few who had gone to high school in the US. At her school, Chinese students had been told not to speak their native languages in the hallway—a miniature version of what happened a few years ago at Duke. The students responded with an angry letter to the school, which their parents, who were paying exorbitant tuitions, signed, upon which the school relented and apologized. She added that while the reaction was effective, it also felt overly confrontational—she didn’t like this way of shouting to be heard, of feeling like everyone was constantly at each other’s throats. While she could sympathize with, say, her black classmates’ grievances, she ultimately found the method of appeal overly strident and alienating. She herself had been attacked for not being “in solidarity” with them.

A few students agreed, softly. Bill mentioned a recent incident in which a USC professor was fired for saying nàgè, the Chinese pronoun “that,” which sounds, unfortunately, like the n-word. Gabe mentioned that in eleventh grade, an African-American exchange student reacted angrily at the offer of a piece of watermelon, and called him a racist.

Caught off guard, I spoke heatedly about how these incidents were just cross-cultural misfires; that identity politics, at its best, does not exacerbate difference, but rather protects it from the monolith of assimilative American politics.

I let myself get defensive. But who was I to say that the lessons I’d fought tooth and nail to learn weren’t readymade categories for a different country, a different time?

The memory of China’s Cultural Revolution, when children could literally sentence their parents to death, has turned many Chinese folks against the politics of moral purity; some intellectuals who move to the States note, with alarm, what they see as a Maoist streak in American public discourse. In call-out culture, they see an illiberal obsession with one’s “true colors,” which must be discovered—or invented—at all costs. The disconnect has created odd bedfellows at times, as Chinese progressives, intellectuals who want to curb the CCP’s monopoly on power and discourse, have made common cause with, say, the American Tea Party.

Even so, race, with its emphasis of phenotype and color, remains a significant (though rarely-discussed) conceptual category in Mainland China, over and above Chinese notions of “ethnicity,” which have more to do with “culture” and “tradition.” It’s not American centrism to point out abuses that Uyghurs, Tibetans, or Chinese citizens of African descent now face.

In the coming decades, it will be a younger generation, like my students’, which no longer sees Western nations as enlightened, superior bodies politic, that sets the tone.

Selina, who spoke with a faint British accent and whom I’d privately thought of as hopelessly posh, wrote her final essay on Toni Morrison’s Beloved, about the long shadow of slavery in the States; Dustin wrote of his posthumous discovery of the letters his grandmother—whose dialect he had never understood—had written to him, a work that reminded me of Ocean Vuong. All my students surprised me by loving David Graeber, who passed away around the time our class began, and hating David Foster Wallace, sensing in him the misleading dead-ends that I spent half my twenties wrestling with, only to end in the same disillusionment as theirs.

Their instincts were better than mine in many ways. And for all my ethnographic pretensions, no 18-year-old was going to emerge from college without experiencing radical changes, as all of us do. I had no idea how they would turn out.

I learned from my boss that the CET program had only a 30% retention rate, and many of my students decided against coming back for a second semester. In a year’s time, I supposed, I would be a distant memory—and so, convinced by their repeated pleas, I flattened my grading curve from a bell to a high hat, and gave them all A-s or As.

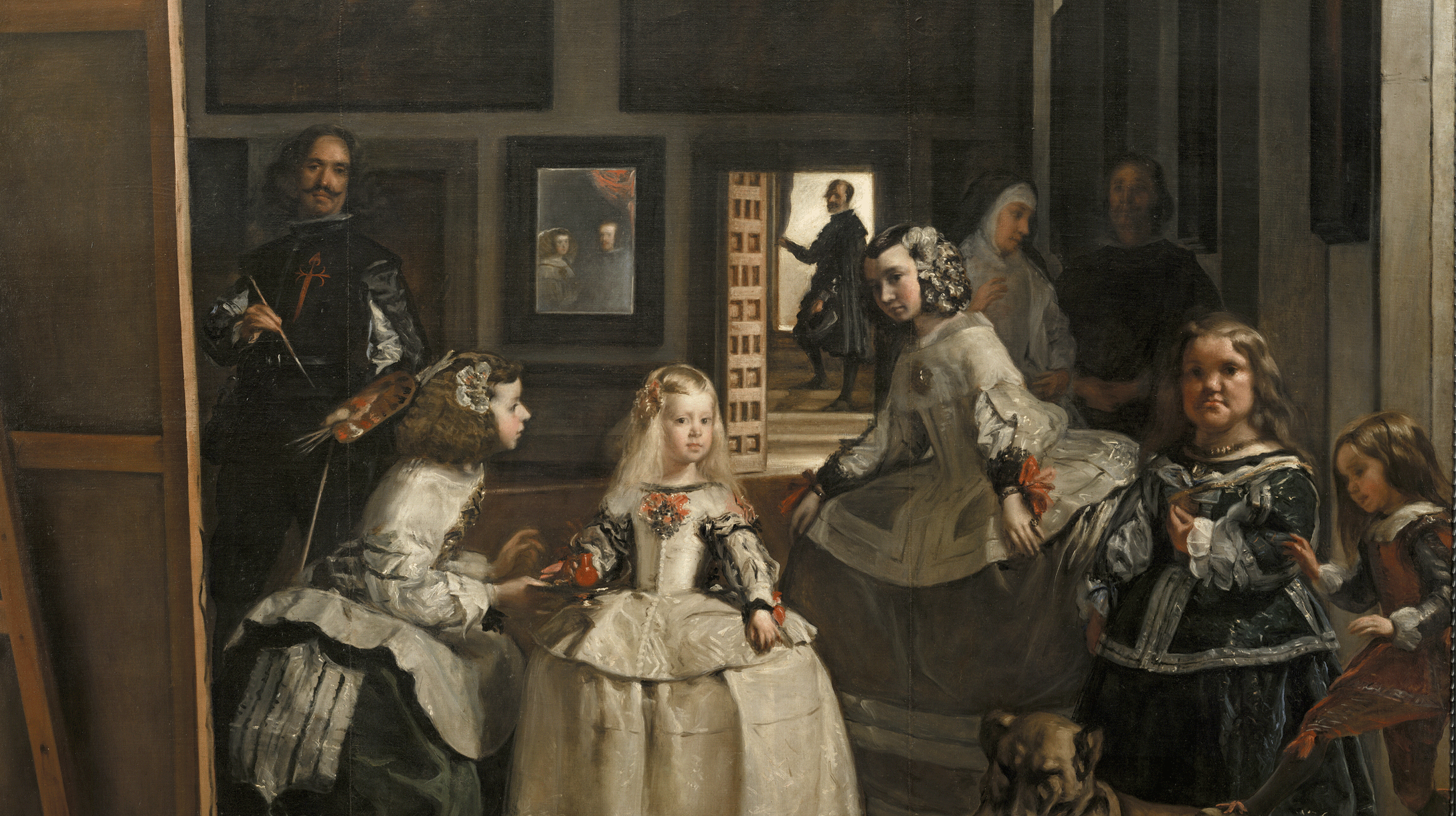

Exactly one week after the presidential election, I took them to a field trip to an art museum where I worked; in class, we talked about The Ambassadors, Las Meninas, and Kerry James Marshall’s School of Beauty, School of Culture. I mentioned the first two artworks’ significance—an anamorphic memento mori, and the strange displacement of monarchy seen from the modern era. I then explained how Marshall had replaced the skull in Holbein’s work with a Disney princess, and the reflection of sovereign and queen in Velázquez’s work with his own, corny mirror-selfie, resulting in a kitschy, ethnic, tongue-in-cheek treatment—the old signs as a comment on the neuroses of beauty and belonging. Marshall, I concluded, felt quintessentially American to me.

My students listened, entranced—not a single one giggled to her neighbor. Afterwards, a few asked me if I felt better after the election. “You were really struggling, last week,” they said. One added, “We should talk about art more, Mr. Zhang.” When I replied that I had no idea she was into this kind of stuff, she said, “I’m not, really. But this was the happiest we’ve seen you all semester.”