In 2018, I went all the way from Ilorin to Lagos—almost 300km—to attend an open mic event. I had only an inkling of what to expect; I’d gone on an impulse, largely to escape the hole of sadness that had engulfed me in my toughest year in medical school. In journeying into the bustling city of Lagos, I passed the ancient town of Oyo, and even Ibadan, the town where my parents lived, without a stop. My parents, God bless their souls, had no idea I was traveling, nor of my depression. In fact, only one of my friends knew of it. I was protective of this sadness, which belonged only to me.

Lagos sweeps people up in its gust, and spits them out if they fail to keep pace. For most Nigerians, being in Lagos is like a chokehold of high-pitched stress. But I’ve been lucky; even on my latest journey, I experienced nothing worse than a mild case of COVID-19. In 2019, trying to escape my sadness, Lagos offered me kind strangers directing me, and, amid the loud din and putrid foul smells of Lagos bus parks, kind agberos holding my hands and calling me sister before putting me in a bus headed to my destination.

Traffic made me a bit late, but I finally slipped into the bookstore where the open mic event was being held. A fresh-faced young woman was reciting poems about a past lover’s abuse. Entranced, I dropped my red bag in a corner and moved into the middle of the room, hanging on every word. It was rare to hear a young woman of my own age speaking openly of her guilt, loving a woman who abused her constantly. There was an air of empathetic kinship in the room that night, and I was quickly drawn into it. Other poets and storytellers mounted the stage— just a stool, really, against a backdrop of bookshelves—and shared their works with us. Young men and women talked about not belonging, identity politics, unrequited love, and new love in their poems, while we in the audience sipped on chilled cocktails, and nibbled roasted asun.

Because Lagos is the place where Nigerian artists live and work, one meets and rubs shoulders with them very frequently there. At this gathering, the star of the night was a singer I’d been following for a while; she held us all spellbound as she sang Seven Lifes by Beautiful Nubia to amazing harmonious accompaniment. Towards the end, with everyone mouthing the song lyrics, I knew I wanted to experience this fellowship again and again.

Over the following months I attended open mic sessions, literary gatherings, workshops and reading sessions in the fine spaces of the University of Ibadan, thanks to Art n Chill. The travel was beginning to wear me out, with the little free time I had as a medical school student. But the weight of my sadness had lessened, and in time, I positively glowed.

The thought of holding similar gatherings in Ilorin, where I studied, had crossed my mind now and then, but the challenges would be great. Ilorin was not a place where literary arts already thrived; unlike the University of Ibadan and some other parts of the country, literary societies in Ilorin were scarce. It would mean starting from scratch.

And then, in a conversation over Twitter DM with a friend I’d met at one of Ibadan’s open mic events, my interest was piqued when he mentioned he wanted to replicate the literary scene in Ilorin. This was in March of 2019. He had not enough contacts, or the time to set it up, but seeing as I had lived five years in Ilorin, he thought I might have better prospects for establishing the community.

Until recently, the literary culture of Nigeria—including bookstores, school departments, and general discourse—has been focused on popular older writers, most of whom have also dabbled in politics and government. But now, across many states from Kaduna to Port-Harcourt to Lagos, new platforms and workshops are emerging for new writers and performance poets of a nascent arts scene. Ilorin was only gearing up to participate in the new movement, at this point. There had been a couple of ad-hoc literary communities in the University, but none had been built to last.

I began with the modest ambition of starting up a regular open mic session in Ilorin. A watering hole of sorts, that was all I wanted. But I knew I had to build a structure around it. The literary interest in Ilorin was too shifty to rely on random sessions every few weeks. I needed a central organizing body, running on days when there were no sessions.

The first thing I did was to slide in the DMs of an Ilorin poet to partner up. I told him of my idea and we set up a meeting, during which we had the idea to build a book club structure with a monthly meetup and regular open mic sessions. The seed was sown. The idea had germinated, and it was time for execution.

It took me about four months to convince myself to move forward. The start of a thing is always scary, but much more than that, I was worried about the reception. Having literary groups was not a thing, in a city where the indigenes were far more focused on Arabic/Islamic-based learning than on Western-style academics. It was not the cool thing to do in a school where literary culture was not encouraged; there would be no precedent or support for our plan in the University’s literature department.

My partner and I launched The Shade Book Club in September 2019. We opened our doors to the public, and not just University students. With our combined influence, we were able to reach a relatively large number of people. Because we had thought to start small, we capped the event at 25 people. Within days we were fully booked, with many more showing interest; clearly, a lot more people were yearning to belong to a creative community. Although most of our members were students, we had doctors, graduates, and even a police officer amongst our members. It was exhilarating.

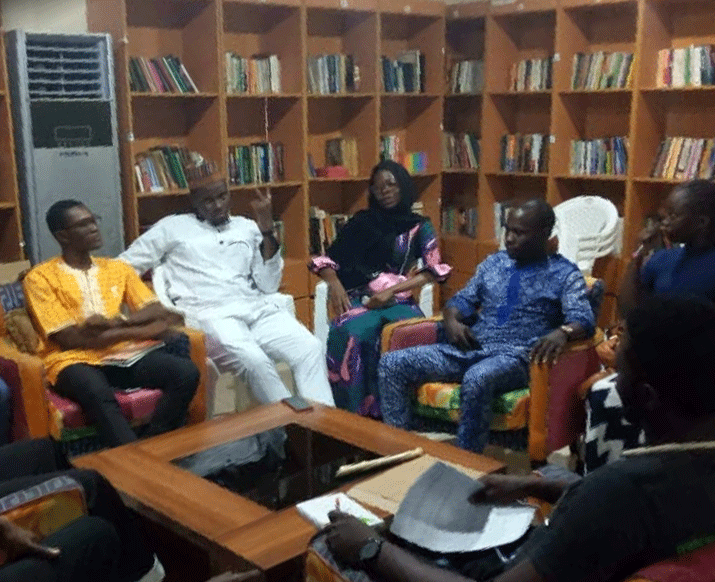

We were able to get the support of a former Minister of Youth Development who resided in the state, and he graciously offered the use of his resources. We were able to hold our book club meetings in his beautiful large library. The organization was a success, we were moving. We were reading in a wide range of genres, from fiction to poetry to autobiographies. And we were talking, and fellowshipping and slowly building a real community.

We held our first open mic session about three months after the book club launch. After hunting for event centers around town, we were able to secure a hall in a new business hub, and they offered us a space for free. Thankfully, it was in the heart of town, easily accessible from most parts. Looking at a maximum of 60 attendees—our most optimistic estimate—we publicized our event, which was free to attend, and called on interested creatives to come to perform.

Just a trickle of people registered in the first few days. Knowing how people were likely to show interest close to the day, we kept on our publicity and waited. I was still in school, so I had the double anxiety of attending clinical rounds while worrying about the success of my open mic event.

The D-day came and I was a bundle of nerves. And then Murphy’s law hit with a vengeance. Everything threatened to go wrong, from the set-up of the venue going awry to the malfunctioning public address system. I arrived later than I’d wanted to because I had to take care of the snacks, public address system and other equipment. But when I arrived, in a panic, I was pleasantly surprised to find the venue all set up by members of the book club. A friend had even brought a standing mic. Also, some members of the audience had started arriving and were conversing. It was the start of a wonderful evening.

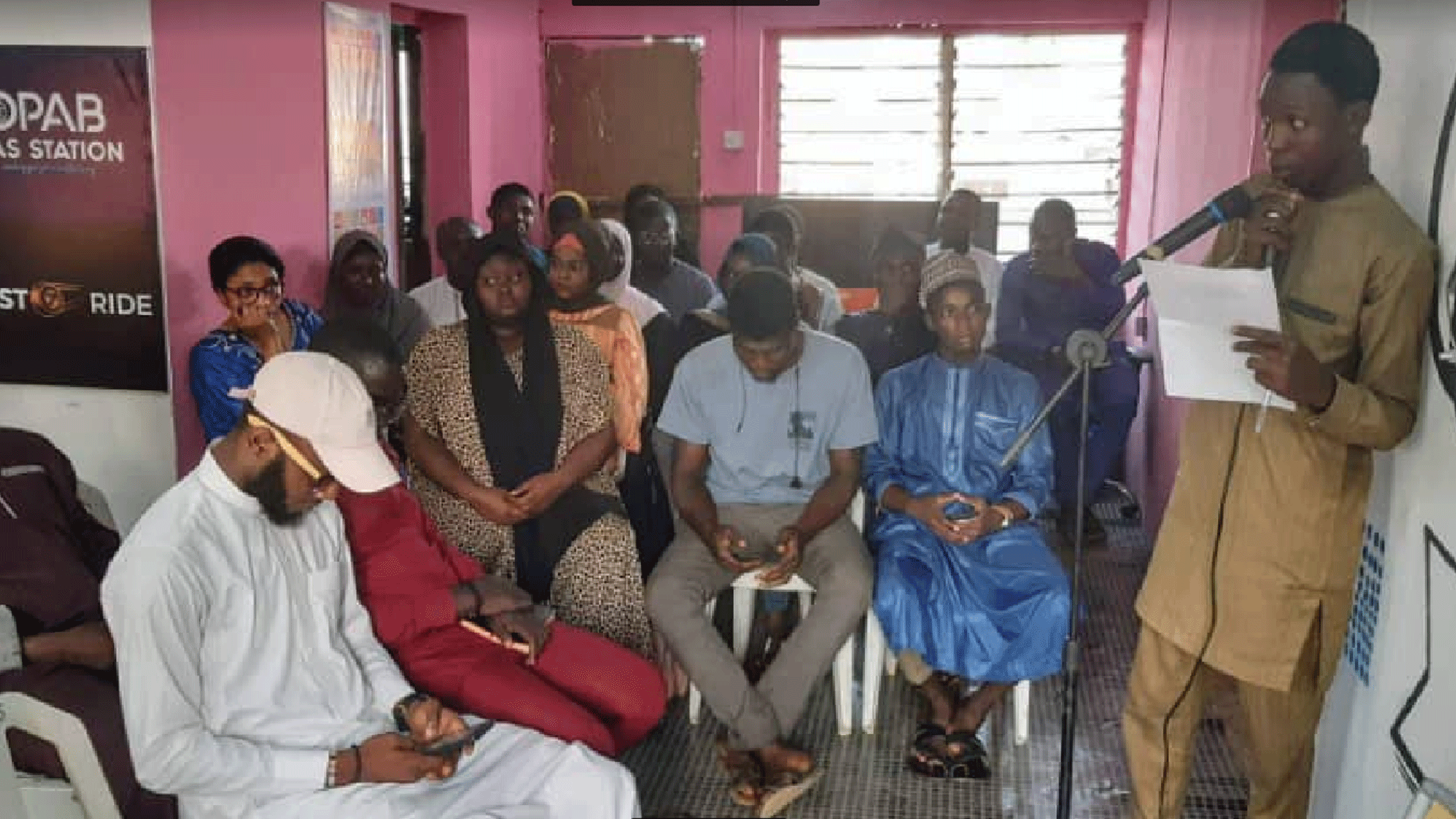

The event was slated to start in the early evening and last till night. Opening the evening at 4:45pm, I read an excerpt from Letters to a Young Poet by Rainer Maria Rilke, admonishing young writers to live a purposeful life within and outside of the arts. The hub kept filling up as I read.

Against the backdrop of flowery art on a white wall, poets stood one after the other to render their poems. Young ladies shared prosaic poems telling of love, of societal inequality towards women. Young men told stories of activism, of love, of cultural identity to the tune of the background music supplied by a member of the book club. The audience went into frenzied clapping and whistling each time a line from the performer resonated with them or caught their attention. The attention was also kept on on social media, especially Twitter with several people tweeting with about the event with the hashtag #TheShadeOpenMic.

Really wonderful!

— Daddy Marjān (@dodo_leleyi) December 13, 2019

Mind-bogglingly amazing!#TheShadeOpenMic https://t.co/pW0yHXSSrQ

More and more people kept coming in, until we were standing room only, even though we had set up a dozen extra chairs. We were treated to freestyle poetry, slam poetry, and even memorized pieces. Poetry from a seasoned sailor, from a CEO in town for business, and from young graduates. But most of the audience and performers were students in various departments of the University. Thankfully, we had enough chilled drinks to go around, and some members of my book club brought extra snacks, even though there were still not enough. The gig kept going on hours into the night as more people were encouraged to share their pieces. More people read their works than those who registered. Even though we all wanted the evening to go on and on, we had to put a halt to the event eventually, as the venue needed to be locked down for the night.

Since this event, there has been the promise of more, new literary communities have sprung up in Ilorin, holding various events and sponsoring fellowships. We’ve been asked to continue the open mic event, to hold book launches and readings. And people are still writing in, requesting to join the book club.