In the beginning of April, as India struggled under through a treacherous second wave of COVID-19 infections, various lockdown-like measures were ordered throughout the country. In Delhi, weekend curfews were implemented. Not that I’d been stepping out before, but the curfew brought along more tightness around our days. A second mass reverse migration of workers came, and a strangely familiar hush fell, as empty spaces again became the norm. Helpless at home, I tried to distract myself by rereading Jane Jacobs’s The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

On the first Saturday of that locked-down Delhi afternoon, I sat on the balcony, staring at the sunlit narrow lane below. Usually, the lane is enlivened by the presence of Chote Lal, one of our neighborhood’s press waalas (ironers), or Guddi, another press waali who works in the open on a stall, standing throughout the day. Ordinarily she would be accompanied by her son, Rishi, a chatty 10-year-old, who cycles around the neighborhood on his red bicycle. With the imposition of curfew, all of them were absent from the lane. The narrow, leafy stretch was as deserted as a highway.

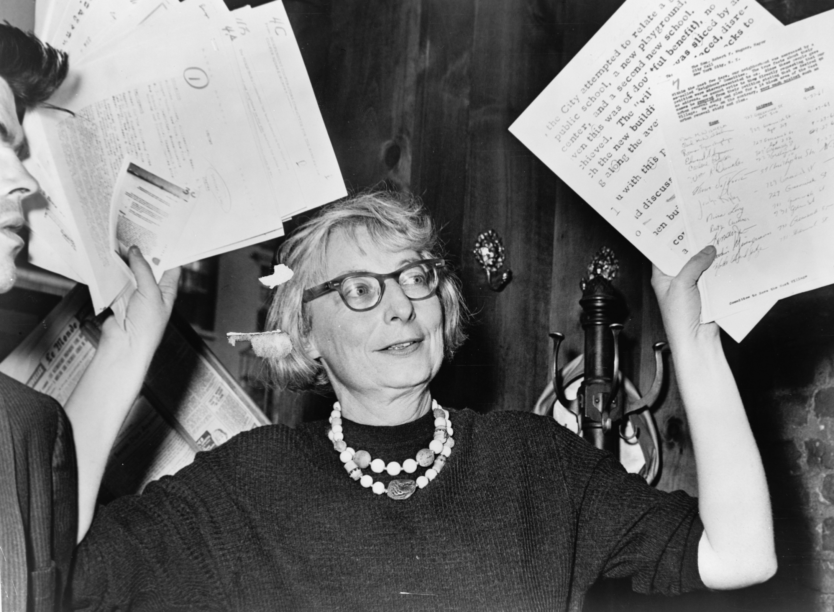

In 1943, while in New York City looking for work, Jane Jacobs rode the subway to unfamiliar parts of the city. One day she got off at the Christopher Street stop and arose, “enchanted,” into the streets of Greenwich Village, which were crammed with tenements, brownstones, warehouses and mom-and-pop stores. This experience would change Jacobs’s life, and the city’s history. She would go on to lead the fight to save the Village and Washington Square from Robert Moses’s plan to build an expressway through the heart of Lower Manhattan.

In writing her seven books, Jacobs drew constantly on the values of her everyday life of a working mother of three, living in the city. She coined the phrase “eyes on the streets” to define the importance of a dynamic street life to the safety and habitability of neighborhoods and communities.

During the pandemic, this phrase became emblematic of the Indian lockdowns. As I measured the streets around my neighborhood, putting one foot in front of the other, I realized how the people holding small jobs, the everyday neighbors we took for granted, had simply vanished from the streets. I found I could not recollect all the hundreds of people who’d defined my own world: The autorickshaw drivers, roadside tailor, chai-waalas, fruit and vegetable vendors, watch repairer, drivers of e-rickshaws, roadside booksellers, vendors of momos and plastic goods, the noodle specialist by the roadside, the man selling jhalmuri, the men and women dusting and cleaning the roads, rag pickers, municipal waste collectors, and so on.

Seated on sidewalks, never taking more space than absolutely necessary, mistreated by the police, manipulated by big vehicles and municipal authorities, the street vendors were all gone. In their absence, the roads were wider, with more space for cars to race through. The new stillness and the quiet scared me. I felt exposed as I walked along, drubbed by the summer sun.

Jacobs developed her observations on New York on the lines of a philosophy very different from the received wisdom of urban planners in the 1940s and 1950s. I mapped the roads of my own sheltered, culturally narrow south Delhi neighborhood with Jacobs in mind

On a reporting trip to Philadelphia for Architectural Forum, Jacobs was dumbfounded by the sight of overcrowded slums leveled and replaced with modernist projects. The people on footpaths were missing then, as they are for me now. Trying to orient myself, and identify whose business stall had been situated where, I took Jacobs’s worldview into my own, creating a mental image of a Jacobs-esque market center in the middle of my south Delhi area. She had argued that every neighborhood needed multiple uses, partly so that it could function 24 hours daily. I tried to draw an image of the mid-pandemic cities of India, had her principles been implemented here.

“On successful city streets, people must appear at different times.”

At all times there would be people around: housewives shopping during the mornings, office workers out for lunch in the afternoons, children playing in the evenings and revelers in bars at night. The proverbial “eyes on the street”, Jacobs said, could help reduce crime.

In mid-April 2021, as cases continued to pile up, the dire lack of trust amid people in my neighborhood grew palpable. Having worked from home for more than a year now, many of us still didn’t know each other, not even by sight. People had imagined that lockdowns would result in better-integrated local communities that would foster regional action, care and vigilance. In reality, we had not hung out with our neighbors in parks, we’d never run into them on pavements or in markets.

Jacobs presciently wrote, “The absence of this trust is a disaster…. Researchers hunting the secrets of the social structure in a dull gray-area district of Detroit came to the unexpected conclusion that there was no social structure.”

Though Jacobs has received her fair share of criticism—in particular, critics have accused her of having been inattentive to issues of race, diversity and class—much of what she wrote back then appear to be directly relevant to our mid- and post-Covid situation.

Before, on days when I needed help to reach for a suitcase kept too high up inside an almirah, or when we needed help to clean the fans, I could just depend on someone, usually Chote Lal, right outside. I’d call him inside to help us, in exchange for money and a meal. Or when I was in need of change money to pay the autorickshaw driver, I could pop in at any of the nearby stores to get change for a hundred-rupee note. The closely knit, asynchronous ways in which we operated our everyday was now, thanks to the lockdown, in shambles.

Jacobs spoke of the “ballet of the street”—the choreography of people of different backgrounds and trades going about their lives in shared spaces. The casual hubbub on the streets of my pocket of south Delhi pocket vanished, a baleful hush descending on our isolation.

This new silence reminded me, too, of the aloofness we had practiced while on the streets, each in a micro-bubble of our own. Oftentimes, walking alone down the unlit street near my house, I would feel threatened by a group of men gathered by the pavement. Or sometimes, walking back from the nearby market, I felt a shudder if an autorickshaw drove by too fast, sounding a bell of caution. I strolled in a pervasive atmosphere of caution. But during the pandemic, in the cold silence of the streets, I realized how all of these people were also the literal Jacobsian “eyes on the streets”. Now, while out on a walk, I yearned for the same density in which I’d once felt unsafe. It felt like a strange comeuppance for not having fully grasped the realities of my own neighborhood. Where were the loitering chai-waalas, the women selling handmade toys on the roadsides and the ambling drivers now? Paan gumtis (shops that sell cigarettes, tobaccos, candies, etc.), street vendors selling daily necessities like vegetables, fruits and also other eatables like seasonal chips, sweet and sour chooran, chai stalls, milk dairies, etc., felt like they were being left behind by the world. Their presence had kept the corners of the frame of our lives aglow, their fascinating ephemera always present, though taken for granted.

The “eyes on the street” theory symbolizes the in-between space, created by these workers, between public and private realms. Jacobs, who would have turned 105 on May 5, considered these “fine-grained” communities to be the natural pinnacle of the human urban environment. She was right. Real, lived-in streets are not only safer but more efficient, less stressful and more comforting for residents. The lockdowns have brought these values back to mind, and I daresay not only in Delhi.