I was on the 395 after the downslope past Sonora Junction bent over the front of my car trying to unhook the chains from my tires in the light of my cell phone when a semi-truck sped past going 50 miles an hour or so. It was then I wondered if $600 for a 1500-word online article was worth it.

The drive was for a story for CityLab, then a vertical owned by The Atlantic about “the future of cities,” about winter in the California ghost town of Bodie. Decades back, the old mining town had been turned into a California State Park. Due to this designation, rangers and maintenance workers had to stay in town throughout the year, even in the winter months when snowfall reaches five or more feet and sticks around.

My pitch was straightforward: What the hell is that like? And to find out, I’d have to see for myself. It was a good pitch but took me a few winters to find a publication to greenlight it.

But standing out there hunched over the front of my car—a 2006 Kia Spectra that wasn’t exactly built for snowstorm driving—something was missing.

Before, when I was writing pieces like this—doing research and conducting interviews well beyond what was asked in terms of word count and deadline—there was always a little voice in the back of my head that said “this will be worth it.” Not for monetary reasons, and not in a “getting exposure” way necessarily. More the idea that the cream rises to the top.

“Cream rising to the top.” What does that even mean in this career?

Like any sort of freelancing, it was about laying enough track in front of the train of rent and food expenses before it barreled me down. Getting a staff writer gig at any number of publications I’d written—and through that, theoretically even in my dumb brain at that point, tried out for—would have meant another mile or two of iron to give me time to figure out what was next. Anything with healthcare would have helped buy time to get a lay of the land and survey what options were available.

Over the decade-plus when I made my income mostly through online writing—here and there were a few short-term gigs, like P.A. work on commercials and odd-jobs like writing entrance exams for rich people trying to get their three-year-olds into illustrious pre-K schools—there was always the lingering idea that as long as I stayed afloat, it’d all work out. All I needed was the right piece to go viral, and with that would come a staff job, enough notability for a book deal, or maybe just a few more editors showing up in my inbox.

The Bodie piece would not get me great exposure. CityLab was paying $600 plus expenses, which isn’t bad, but there was something missing – the voice. That voice of hope for an actual career was silent.

****

If I were to go back in time to send Young Ricky a message, it would be to burn his copy of Get a Freelance Life.

Released in 2006—that era when the freelance lifestyle was being heavily sold; don’t worry about “job security” or “healthcare,” imagine “working from the beach!” or “being your own boss!”—it was an “insider guide to freelance writing.” It was put together by the editors at Mediabistro, a subscription website where writers could learn how to pitch, what pay rates were, and scroll through job listings. The first two categories have been taken over by some combination of Twitter and places like the Freelance Solidarity Project and Study Hall. I don’t know if media jobs exist anymore.

Before I bought the book, I’d been thinking about quitting my job, a full-time gig in Los Angeles with no future. I was compiling compilations of TV segments for marketing folks at movie studios who wanted to see the types of media pickups their summer blockbusters were getting. Here’s an example: I’d send over all of Tom Cruise’s interviews on Letterman, Leno, and Extra about Mission: Impossible. That kind of thing. But I had a lot of downtime between assignments and an internet connection at the office, so, it was the idealized version of a “bullshit job.” Between sending out those dumb movie pickups, I’d post on forums and read blogs. By then I had a few bylines to my name, mostly sports joints like ESPN and Deadspin. I got those gigs because I had a regular byline at McSweeney’s. I wrote a fantasy baseball “advice” column for years for a grand total of $0 but that byline gave me an in.

With time on my hands at work, I began pitching more. VICE, the various Gawker enterprises, ESPN the Magazine’s website, a few local blogs that paid $50 for a bar review, etc. You get it. Slowly, I pieced together an income outside of my full-time job, and once that freelance income added up to roughly half what I was making, I decided to quit. With the insight and confidence lifted directly from that damn Freelance book, I gave the “lifestyle” a shot. Off to the beach!

The first year was difficult. I plowed through my savings and made $5,000. I got up to $30,000 the next year, which made it more manageable but not great. Soon I got up to about $40,000 just on pitch sweat alone, and that’s where I roughly stayed for the next decade, no matter who I wrote for, how many pieces I wrote, or how prestigious the publications were. There was a built-in ceiling that I didn’t quite know existed yet.

But who cares? The next step anyway was a staff job, or one of those deluges of income because some piece hit right, and that would give me the life raft for a year or so. All I had to do was work hard! It was a meritocracy, after all, and I was becoming a strong writer who someone would notice—they simply had to. And with the exposure potential of the entire worldwide web, it was only a matter of time.

The publications I wrote for between then and now are a trail of the dead or dying, a few biggies spaced in between:

Radar, The Awl, SB Nation Longform, Pacific Standard, Deadspin, ESPN Page 2, The Kernel, The Morning News, The Daily Dot, VICE Sports, Free by Vice, Broadly, Atlas Obscura, Nerve, HuffPost, The New York Times, New York’s Select/All, New York’s something but I forget now, Columbia Journalism Review, The Atlantic, Terraform, Curbed, Longreads, Splinter, Popular Mechanics, Vocativ, San Francisco Weekly, KCET, East Bay Express, OneZero, and probably some more I don’t remember or that have been erased from the internet entirely.

I still have links up on my website but I barely keep it up anymore. This is the third or fourth such portfolio I’ve made over the years, ostensibly to show prospective editors I’m a legitimate, highly sought-after professional writer. But it’s really for me—it provides evidence that I’ve written decent things before. Some of the links still work.

****

I used to believe that if a story I wrote got enough traffic then the editor would give me another assignment or, in the best-case scenario, I’d get a steady gig. So I’d email my stories to the various “tips@website.com” addresses of popular blogs that needed links for their weekend round-ups. Sometimes I’d post my story on relevant message boards, or I’d slap a snarky headline onto Fark.com to lure those hits. When you’re a freelancer, you have to be your own billboard as best you can.

In my 15-year “career,” I realized that editors at publications largely treat freelancers, well not exactly like shit, but very close to it. Maybe not through any fault of their own. It’s the system mostly.

Like, this one time Sports Illustrated greenlit a $500 piece about MLB players with only one game of major league experience. After I turned in a 3,500-word piece that I easily put a month of work into, the editor’s response was simply: “This isn’t what we were looking for.” No kill fee, no nothing. (Okay, that was definitely a shitty editor.) It did end up living here, for a very nominal fee, but who knows how long that link will last.

Last year, toward the beginning of the pandemic, I lucked into a steady copywriting job. Not through any writing credits of mine, mind you, I want to make this clear. It was just because I met someone at the right time while playing softball in Oakland. For the first time since 2007, that meant I didn’t need to pitch websites to eat and pay rent. In the time since as it’s—luckily, thankfully, etc.—continued, and has given me a little perspective on how fucked the journalism industry is, especially for freelancers.

I’ve seen people turn journalism degrees into jobs, but that’s less because of skills they learned as much as just buying into the right social circles. The non-degree route for a career as a professional journalist is just the same as it always was: move to New York City.

Beyond that, though, it’s important to keep in mind that, in the year of our Lord 2021, every dumbass knows how to write.

Which is fine! But, because of this, there is simply no reason for publications to add a staffer when they have quality-adjacent freelancers fighting each other for word count space. I guess I wonder why some writers still do it. Maybe it’s for the rush that comes with posting a link on Facebook to old high school friends who have no idea how the industry actually works? But I hope some of them still want to make a difference—or just have amazing experiences—because there’s value in that. Although it does seem like those days are just about over.

***

The piece about Bodie was one that I’d wanted to write for so long. The place fascinated me—like, it was truly one of the most unique places on earth. And, in order to write it, I needed a publication’s backing that allowed me access, or maybe just an excuse, to visit the ghost town in winter. The $600 fee (plus expenses) was good—another bit of rent is nothing to sneeze at—but it wasn’t why I wanted to do it.

And so, after I cheated death via semi-truck and finally pulled the chain off my front tire, I got back into my Spectra and drove another hour-and-change to my motel room. The next day I got a lift from a ranger and walked the grounds, all to actually experience winter at Bodie, the ultimate goal. The $600 is long gone by now, but that day at Bodie—when no one else was around and we hiked through snow piles to peek into old structures—that’s something that I’ll always have.

If there is any advice in this long piece, that’s it.

Credits don’t matter anymore. Money matters a bit, but there are better and easier ways to make it. The only reason to write isn’t for other people reading at home or for your possible career, so it better be for your goddamn self.

****

A few months after my Bodie piece was published, Citylab was sold to Bloomberg for however much money. They still have my article up at their site. There are six advertisements still attached to it.

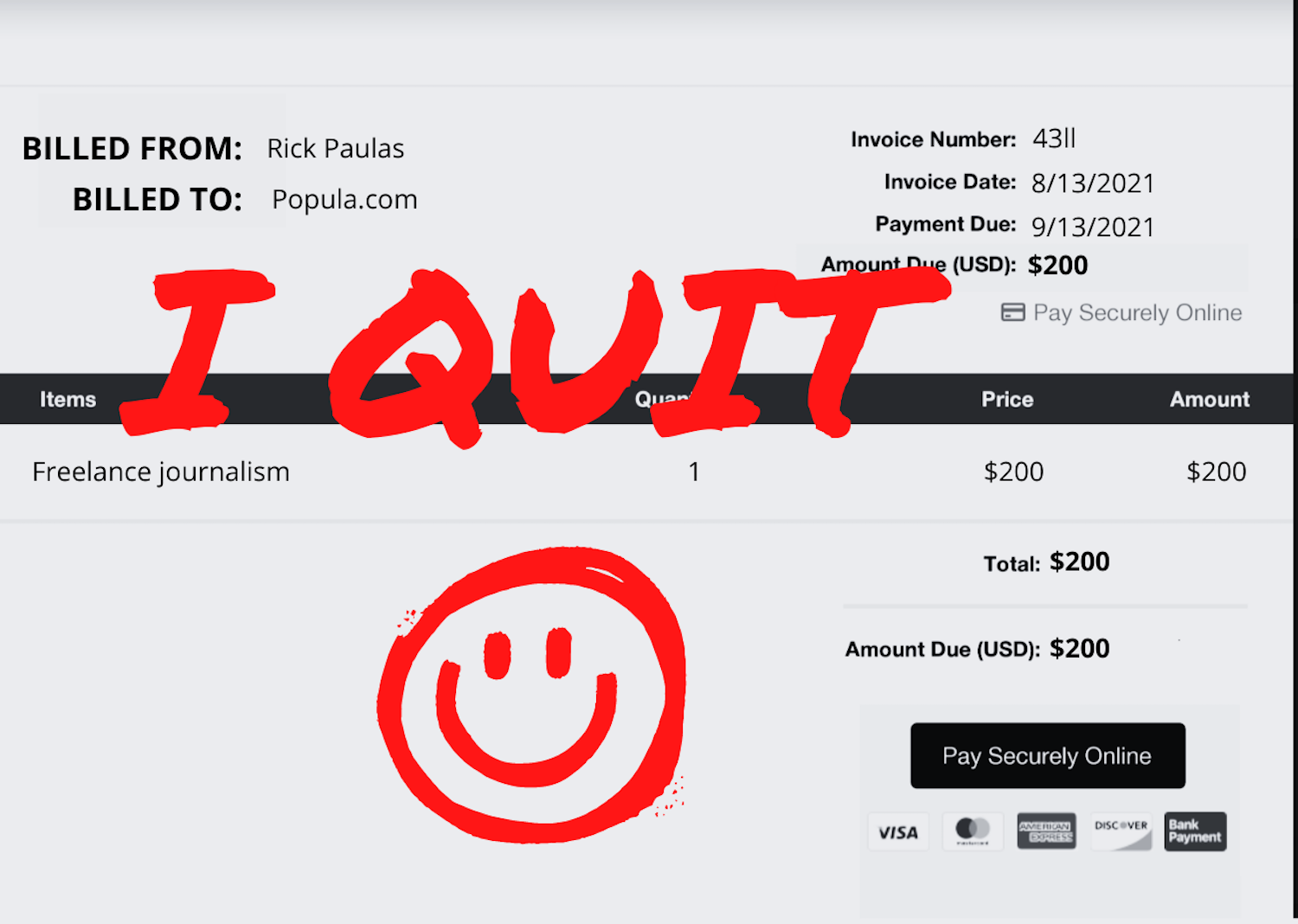

Rick Paulas is a poster-about-town currently based in Brooklyn who is selling a new book of spooky short stories ($20, and that includes shipping) and also tweets a bunch.