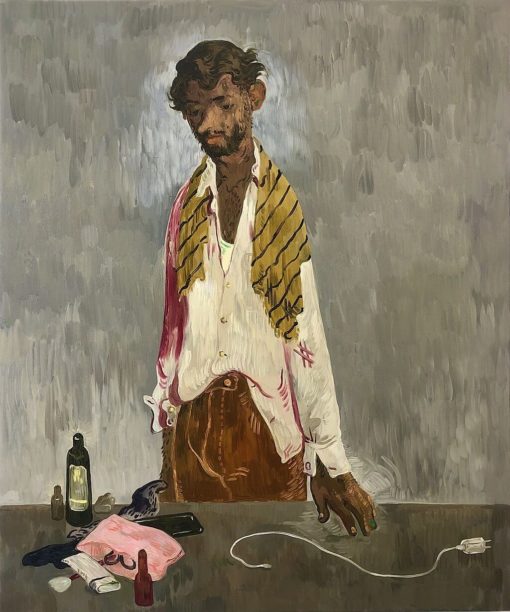

Man with Face Creams and Phone Plug is a painting of a brown man with his head down—in just the way I’ve always held my own head down at airports—as he waits for an immigration or customs official to go through his belongings. The man’s submissive manner, and the personal things scattered on a surface before him, tell us that this is a scene at an airport; we are accustomed to seeing South Asian people patiently standing and waiting at customs and immigration counters in this same posture. It wasn’t until I saw a Salman Toor painting that I realized I had never seen someone like me depicted in a painting before.

Toor is a Pakistani-born artist based in New York City, whose subjects are queer brown men in ordinary, everyday scenes in America: texting, taking selfies, or socializing in small apartments. He describes his characters as “the kind of people who sometimes succeed in merging irreconcilable ideas of the culturally Muslim immigrant, and the literary and artistic libertine in the Western tradition.”

I first encountered Toor’s work in an essay in Gossamer magazine, in which Amitava Kumar described the painting East Fifth Street as a “statement about brown style flowing through the streets of New York City.” Here, a stylish brown man with “a long colorful scarf thrown around his neck” smokes a cigarette outside his East Village apartment as a policeman walks past.

The composition recalls Edward Hopper’s New York Pavements, but while Hopper’s doorway is empty, with a hurrying nun pushing a stroller the only figure present, Toor’s entryway is inhabited by a graceful young brown immigrant, dreamily smoking a cigarette and claiming the building as his own. It’s a sublimely ordinary statement: Toor is inserting brown men, casual, obvious, unremarkably at home, into the cosmopolitan world of the western canon. The NYPD officer strolls by, oblivious, finding the scene unremarkable.

The figure exudes “insouciance” and “elegance,” Kumar wrote, and “blew smoke with such nonchalance,” that he seemed to be “untouchable.”

But can an immigrant ever be “untouchable?”

Why do we keep our heads down at the airport? It’s pretty obvious, on one level; customs officials have, however briefly and however pro forma, the power to change anyone’s life completely, instantaneously. Indeed the first thing I noticed about America when I first arrived was how intimidating the immigration officers were.

“Grab your stuff and follow me,” the officer in the stiff all-black uniform said sternly as he escorted me to a separate room at O’Hare Airport.

There, another officer, just as hulkish but more relaxed, flipped through my green Pakistani passport. My eyes lingered on his crisp black badge-laden uniform; when I spotted his gun I quickly looked away, and ended up staring at his face, which was now locked into the computer screen. It seemed rude to stare, so I lowered my gaze to his thick fingers typing loudly on the black keyboard. Afraid of giving the impression that I was trying to decipher what he was typing, I looked away again, finally finding refuge in contemplating the thick plastic folder full of documents in my hands.

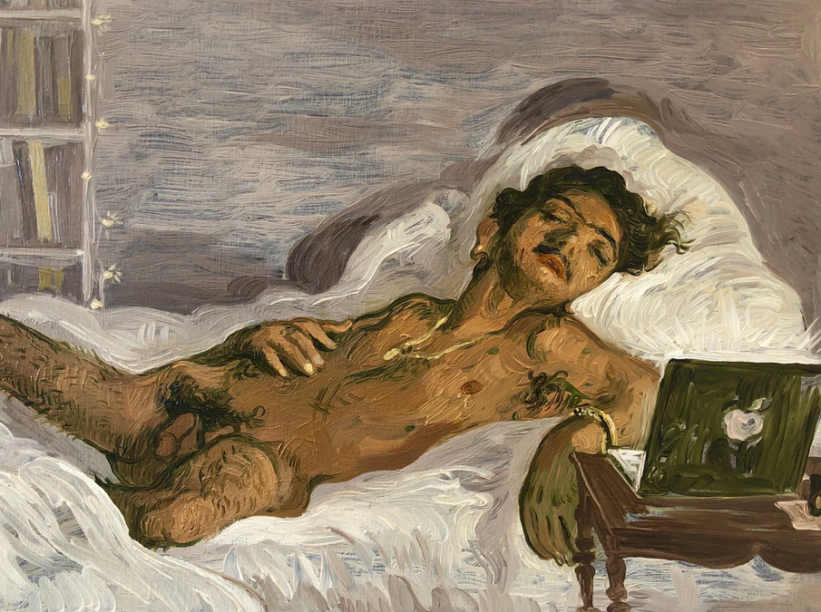

“Oho, desi lund,” my friend remarked as we arrived in front of Toor’s Sleeping Boy at the Whitney. Lying naked in the glow of a MacBook was a young South Asian man and I wondered, as my friend pointed out, if I had ever seen a desi circumcised lund resting on a curly-haired thigh in a painting before. I had not. And seeing one made me feel oddly proud of having a penis worthy of being depicted in a painting hung in a museum.

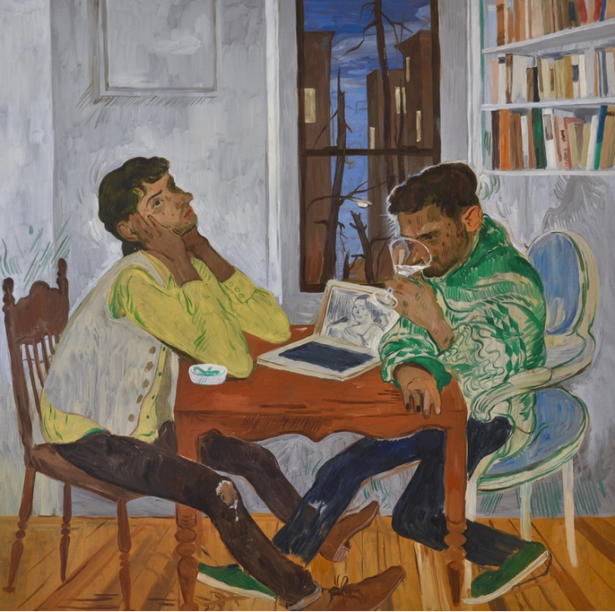

Faces illuminated by the glow of open laptops or iPhones are a recurring theme in Toor’s work. In East Village Iqbal Bano, two stylish boys sit on mismatched chairs. Their apparent comfort in each other’s silence shows they are good friends. The boys, presumably immigrants, are dressed with Pakistani flair: one is wearing a yellow sherwani-collared coatie, and the other is draped in an embroidered green shawl. There is a laptop propped open on the table between them and it is playing a YouTube video of an Iqbal Bano, a popular Pakistani ghazal singer in the 70s. (Ghazals are poems about love — often about heartbreak) As a homesick freshman in an American college dorm, I too sought refuge in YouTube videos of Pakistani songs. Toor told Amitava Kumar that his paintings are “direct, unplanned, autobiographical, and illustrative.” He was raised in Pakistan and went to college in America, just like me, and seems also to have had this experience: sitting in silence, listening to ghazals.

“We don’t want them here.”

“Trump Bars Refugees and Citizens of 7 Muslim Countries.”

New York Times. 27 Jan 2017

Every South Asian person I know has an immigration or US airport story to tell. Some are told in a joking manner, while others are more serious. My father loves telling, with a big laugh, how the immigration officer panicked when my father told him that he had snacks in his luggage. The officer thought my dad, presumably because of his Pakistani accent, had said, “snakes.”

A friend told me that the immigration officer took his cellphone and read through his texts. “Can they do that?” I asked. “I guess so,” he replied.

Vahideh Rasekhi, a Ph.D. student studying linguistics at Stony Brook University, hugged friends who greeted her as she walked out of Terminal 4 after being detained since flying into Kennedy Airport at 1:45 p.m. on Saturday from Iran. When asked if she felt angry being detained she said: “I don’t feel angry right now. I am so happy it’s done.”

– “Highlights: Reaction to Trump’s Travel Ban.”

New York Times. 29 January 2017

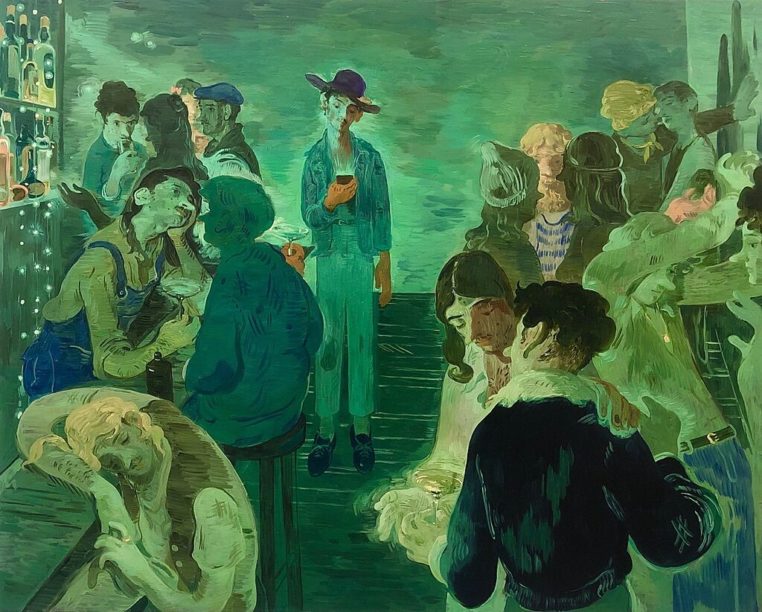

A number of the works in the show at the Whitney share a deep, emerald-green background. Toor tells New York Times, “There’s something glamorous about it [green], there something alluring but also poisonous.”

For the many of the brown immigrants in Toor’s paintings the green hue is similar to their lives in America – glamorous, alluring, yet poisonous – as they hope to make a permanent home here and get a green card.

“People are curious to know what it means to have the freedom of so much choice,” Toor elaborates about the questions he explores in his paintings of queer South Asian life in America, “and what is the nature of that freedom what is the cost of that.”

Bare walls serve as the background in many of Toor’s paintings: Four Friends, Bedroom Boy, and Sleeping Boy, among others. No matter how joyous or relaxing the scene unfolding in front of us, the bare walls suggest that Toor’s apartments are temporary housing, and perhaps even that there is a chance that his subjects will be asked to leave the country sometime soon.

For many immigrants on temporary work visas, Kumar writes in his 2000 book Passport Photos, their “universe is reduced to those documents that define [them] in relation to the world. All that matters in this life – in this portion of life that an immigrant hopes will not last forever, though in some cases it does – are the passport photos and the stamp on the visa.”

The walls of my own living room in Greenpoint, too, are bare. “You should hang something,” my friends tell me. Two canvases, acrylic paintings by my mother, lie rolled up against the wall. “Just frame it and put it up,” another friend tells me. I can’t, I say, because I am lazy and because framing is outrageously expensive. But it is not the full truth: framing is ridiculously expensive, but the real reason is that I am scared to put the paintings up. I’ve told myself every year, for the past ten years, that I am ready to leave the US if my visa isn’t renewed. Hanging a painting on the wall would mean that I am confident that I will be staying here for a while; it seems like an open challenge to the visa gods.

“The bare walls are a reminder,” a friend of Kumar’s tells us, “that America wants our labor but not our lives.”

Toor has revisited the same immigration scene, the one at the airport and with the officer, many times over the past decade. In his painting The Jetsetter, part of his 2015 show Resident Alien at Aicon gallery in Lower East Side, the same scene is showed with a young Pakistan boy, as he presses his left hand on the fingerprint scanner and an immigration officer with blue gloves has a hand over his i-20. In the background is a line of immigrants all with their heads bowed down as they wait their turn. Flickering in the background are scenes from the immigrant’s life – his visa stamp and a moment shared with a friend – as Toor tries to capture how a whole life is reduced to a single moment.

The painter revisited the same scene in 2017 in an untitled painting where the same immigration officer is interacting with the same boy in the red hoodie, possibly from the perspective of the other brown person waiting in line behind him, amidst surroundings bleached by the white overhead lights of the immigration counter.

The label on the wall beside Man with Face Creams and Phone Plug describes the painting as a self-portrait, but I see it as a mirror. I feel the bare walls around the man are, instead of an airport, the sparse walls of the Whitney around me on this slow Sunday afternoon. And the man with his head down is a reflection of me as I relive the moment again.

How will I know if he really loves me? How will I know?

Don’t trust your feelings

The name of the exhibit is borrowed from Whitney Houston’s 1986 hit song “How Will I Know.”

In his Gossamer essay on East 5th Street, having claimed that the painting’s subject is ‘untouchable,’ Amitava Kumar asks his eight-year-old son to offer a reading of Toor’s brown immigrant. The child replies: “The policeman is going to arrest the Indian guy who is probably a Muslim.”