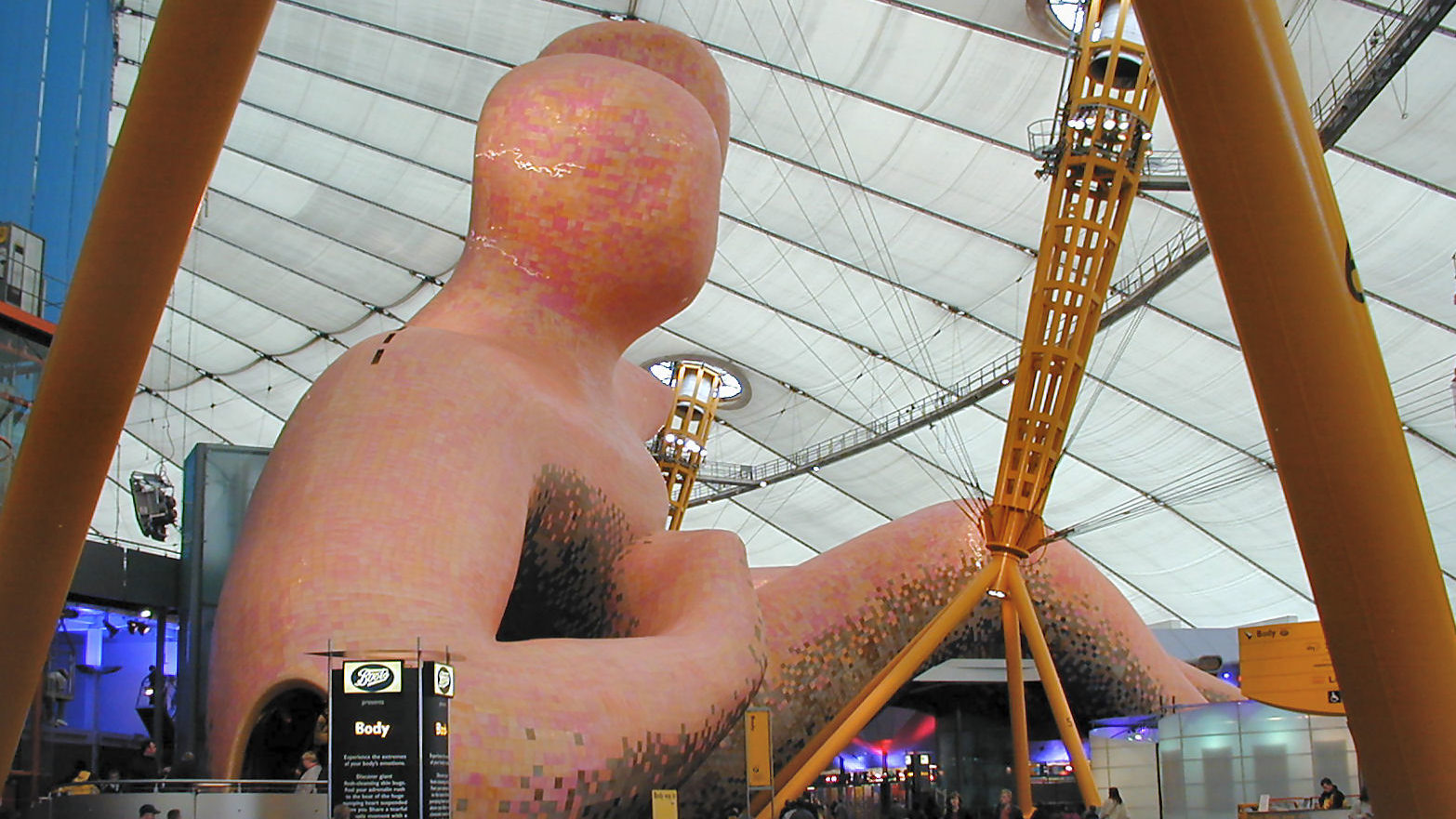

I remember the day in 2001 my best friend told me, in the school cafeteria, that she was having night terrors over the memory of a monstrous god-sized heart. To celebrate the dawn of Y2K, a new era where anything was possible, her parents had taken her to the “Millennium Experience” in Greenwich, London, a long-awaited exhibition into which the government had poured £789 million. It was here that my friend had entered a labyrinth called “The Body Zone”, a sculptural maze designed to teach visitors about human biology, as they walked through the right arm of an enormous man and through the interior of his torso, before making their escape through the left heel of the equally enormous woman with whom he was entwined.

“The huge Body Zone at the centre of the Millennium Dome is nearing completion,” the Architects’ Journal had announced before the opening:

The Nigel Coates-designed body is a large sculptural form of a man and a woman. Visitors will pass through an exhibition space within the body located 7m above ground level.

Underneath the 64,000 shiny gold lenticular tiles of the skin are 180 tonnes of steel. A central ‘skeleton’, designed by engineer Buro Happold, provided a stable stand-alone platform from which to build up a series of ‘skin hoops’. This skeleton consists of straight steel sections, with the exception of the enormous male foot which is cone shaped, cantilevered 15 metres out from the rest of the body.

My friend did not know who Nigel Coates was, but she remembered being trapped in a series of red pulsating corridors, her hand clinging sweatily to her mother’s, trembling at the sight of a heart that was twelve feet tall and throbbing with uncanny vigor. (“Over the whole year, the heart will be beating more than 20 million times.”) She did not like it. She did not like it one bit.

Some weeks later, I visited the Millennium Experience myself, lured by a prospect no child of the 90s could resist: there was a free event near the venue where kids could download Mew, the legendary special-edition Pokemon, into their copy of the Game Boy game. I don’t remember being as horrified by the Body Zone as my friend, but I do remember roaming through the exhibits with a vague sense of purposelessness and confusion. There was no overall theme or message, only a collection of oddities the creators seemed to think were neat. From the depths of my childhood memory, I can draw out a pink yonic cavern in the “Rest Zone” where attendees were invited to lie down for a bit on a hard pearlescent floor, and a commemorative five-pound coin in a glass case. I also feel very strongly that there were massage chairs but can find no evidence for this.

The Millennium Experience was supposed to be a celebration of both Britain and the world; a tribute to humanity as we passed into a brave new world of flying cars and perpetual peace. Instead it ended up as a national joke. What is the connecting ideological, material or teleological thread between a commemorative coin, a massage chair and an escalator ride through the gastrointestinal system? What happened to our future? What did Tony Blair do with it?

To be fair to Blair, the Millennium Experience was not his idea. Like his ideology, it was more of a continuation of a project started before him by a Conservative government. The idea to celebrate Y2K with a World’s Fair type exhibition had been floated by John Major’s government in the early 90s – perhaps one which could be housed in some sort of custom-built dome, no doubt inspired by such famous demonstrations of Britain’s ingenuity and power as the Crystal Palace Exhibition of 1851. But it was the Blair government which expanded this vision, bloated the budget, and made the Millennium Dome infamous. The plan was to create an exhibition that would not only summarise all of human achievement, but illuminate the way for the glorious future ahead. In the years running up to launch day, Blair said Britain had “a thousand days to prepare for a thousand years”.

But the brains behind the Dome appeared oddly short of ideas. Construction began in June 1997, on a tent-like structure resembling a sort of half-built Koopa shell, while everyone was still drawing a blank on the small matter of content. Following the unexpected death of Princess Diana that August, it was briefly suggested that the Dome site be dedicated as a memorial to her, but that idea went nowhere. A hodgepodge of cultural consultants gave their vague input, most of which led nowhere too. As the date grew near, it was settled that the exhibition would be made up of a cluster of “zones”, each representing some aspect of the human experience. The exhibit within was to last through the year, after which someone would have to decide what to do with the giant tent that now squatted in Greenwich. Content was rushed in the runup to New Year’s Eve, in order to be ready for a grand opening night.

That opening night was disastrous – a disaster Britain was primed for, as the Dome had already been the subject of criticism for years. Media coverage was cynical; many would-be attendees never received their tickets, there was a hoax bomb threat, and long delays getting the punters inside. The Millennium Experience was originally expected to attract about 12 million visitors throughout its year-long run, but the total ended up being closer to half that. Jokes abounded about what a disappointment it was, how aimless and anodyne. A common email forward of the time compared the Millennium Dome to breasts in a Wonderbra – “looks impressive from the outside, but fuck-all of interest when you get in”.

So what had Blair’s dream teams actually come up with? The Body Zone, where my childhood friend had nearly collapsed in terror, was an education in human anatomy sponsored and supported by L’Oreal, Roche and Boots, three of the biggest companies in the health and beauty industries. The exterior, seemingly based on a male and female body fused together in a stress position, looked like something between a child’s slide and a Lovecraftian menace. (While I don’t believe that aesthetics dictate politics, it fails to surprise me that the Blairite soft-left wave which created this horrorshow Zone, its angry pink two halves reluctantly clinging to each other, appears currently to be committed to virulent queerphobia.)

Inside the “womb room”, visitors would watch a video of a sperm entering an egg “set against a soundtrack of tribal, war-like African drumming.” “The film is designed to be exciting and entertaining and we have sought to show the sperm behaving like a tribe of predatory fish”, said the head of the team behind the film. “There are moments of humour as well. We will show an idiot sperm attempting to swim the wrong way before it is caught and overtaken by the others.” Other highlights of the Zone included an electronic screen where visitors could try on different haircuts, and a stage where a disembodied brain-on-a-stem representing the dead comedian Tommy Cooper would “deliver” Cooper’s jokes, while other brains sat in the balcony and laughed. If you find this concept difficult to imagine, you’re in luck. I found this picture on someone’s old website, which clarifies nothing, but does make the idea much more horrifying.

In addition to the notorious Body Zone there were thirteen other zones, each produced by a different set of creative teams and corporate sponsors – “Journey” by Ford, “Talk” by British Telecom, and so on. “Faith” managed to get away without an affiliated sponsor, following pressure from religious leaders, though arguments about whether it was too Christian or not Christian enough blighted the effort, resulting in a bland CliffsNotes depiction of the UK’s major belief systems, trying in typically weak-minded New Labour style to appeal to everyone while ultimately saying nothing. “Mind,” meanwhile, was sponsored by two arms manufacturers, and was guarded by a statue of an enormous squatting boy. “Work” was sponsored by Manpower, the employment agency with a particular enthusiasm for what would eventually be dubbed the gig economy. Here, children were invited to watch hamsters spinning cheerfully in their wheels, think about their skillsets, and encouraged to play interactive games that would test their future employability. (“Accurate number skills can mean more choice and flexibility in the world of work. Are you up to scratch?” asked one exhibit, before challenging children to a math problem.) In between zones, families could eat at the two in-Dome branches of McDonalds, or view one of the regular performances of “OVO”, a Cirque du Soleil-style show boasting an environmental theme, though many expressed the view that they could not understand the plot of the show at all. (Incidentally, circuses are fun but if the government had actually done something serious about climate change at the time, we would be in a significantly better position now.)

All of this was supposed to add up to something – a celebration of the present, and a salute to the future. But what vision of the future did the Millennium Experience actually present? The tone was optimistic, but the content offered little to actually be optimistic about. Instead, visitors got art-by-committee, megacorp overseers, hippie aesthetics without the values, and “choice and flexibility in the world of work”. In other words, the exhibition was Blair’s legacy incarnate.

Anecdotal evidence suggests visitors to the Dome typically found it a fun day out. I think I enjoyed myself, although that might have been more to do with my limited-edition Mew than anything else. Still, as I delve back into my own memories and old archived pages on the internet, I keep thinking about all the weird detritus that ended up in the Dome, much of it so meaningless that it just got thrown away after the exhibition ended, or else bundled off and sold for pennies like so many pillars of the welfare state. I also think about the Childhood Cube, a Perspex-and-steel sculpture created by artist Sarah Raphael in conjunction with children from multiple schools in London, which sat in the outside grounds. The children of the generation who saw this exhibit— even the children who made this exhibit—grew up and were launched into adulthood on the cusp of the biggest economic crisis in a century, and it was here that the UK government made it clear what kind of world this generation would inherit: temporary jobs, empty promises, and a new horror lurking around every corner. Can you see your future in the cube, child? And at night, when the streets are quiet, can you hear it? Can you hear the terrible beating heart of Britain?