My Dad used to creak open my bedroom door in the middle of the night and mumble, “I can see your light is on from under the door, go to bed.” A favourite, familiar memory. I loved reading, and staying up late with a torchlight in the otherwise dark and quiet house was a treat. With sounds magnified in the dead of the night, I could hear when anyone woke and left their room, so that I might quickly turn off the torchlight and pretend to be asleep. But sometimes I’d become too engrossed in what I was reading, and my dad caught the hint of light coming from under the door.

Power cuts and outages have been the norm in Nigeria all my life. As I was growing up, having power during the day was not expected; when it came on, shouts of ‘Up NEPA!’ echoed through the streets. And so we had to seek an alternative in noisy petrol-fueled generators, the size of which varied. Almost every house had one; having a generator was a thing to brag about, the bigger the better. So much so that these petrol engines were nicknamed ‘I better pass my neighbour’, the neighbour meaning those without.

It’s a kind of cultural touchstone: every Nigerian child who grew up middle class knows that the time for turning on the generator is 7 pm. It is known. Also known: the generator was to be switched off by 10 pm, after the NTA network news, or possibly 11 pm if your Dad falls asleep and doesn’t harangue you to put it off. The streets, pulsating with the noise made by dozens of generators, gradually went silent as the night fell, and after that I had no choice but to resort to my trusty torchlight to read.

“You can read it in the morning, do you want to damage your eyes?” my father would demand.

The damage, perhaps, had been done already. I’ve always needed glasses. Doctors say it’s hereditary—my father, mother and now younger sister all use glasses—but my father is still convinced that reading in dim light is the reason for my defective vision.

Nigeria has twenty-eight power plants—a combination of hydroelectric and fossil fuel power plants—for generating electricity. However, the combined capacity of these plants has dropped by 70% in the last year. About 43% of the population is not connected to the national power grid, but those who are connected must contend with incessant collapses—there’ve been at least six this year alone. The chaotic supply is leaving people at the mercy of these fossil-fuel-powered generators, more than ever before.

With Nigeria’s inflation at 19%, the highest in 17 years, coupled with an unstable and constantly devaluing currency and rising fuel prices, petrol generators are unsustainable. Again, alternatives are sought, and leading these is solar energy, a solution that is increasingly being adopted by households, small businesses and even institutions in Nigeria. Smoke-free and quiet, solar is finding increasing acceptance despite certain drawbacks.

“I’ve always hated the noise of generators, but I didn’t have much choice,” says Latifa Azeez, a hairdresser with a shop on a narrow street in Ilorin. “Sometimes the breeze blew the fumes towards the shop. That, particularly, was an inconvenience to me and my customers.”

Latifah got a 0.5kva solar inverter installed in her shop last December, which cost her ₦57000 ($135.42). The cost was high, but during a period of fuel scarcity in December, she decided to shell out the money. It turned out to be a good decision.

“Over weekends and during celebrations like Christmas, Eid and Easter, I have many customers, and have to stay late at night. I got the solar [unit] instead of having to pay every day for petrol, especially now that the price has increased and we had to queue at the filling station sometimes to buy it.”

Not having to pay maintenance and repair costs, as in the case of her old generator, is another solid advantage. She hasn’t had any problems with the solar inverter since it was installed. “As long as the sun is up there, my bulbs and fan will be on.”

Even though the solar unit in her shop can’t power certain appliances, like her dryer and curling iron, it’s enough for Latifah’s illumination needs at night. She got a DC fan for her customers in the daytime’s sweltering heat.

Though it’s one of the biggest sources of carbon emissions in Africa, Nigeria does not contribute significantly to global greenhouse gas emissions. Environmental awareness is low here, despite the country’s vulnerability to climate change. The principal motive for the growing demand for solar units is a practical one—reliable access to energy. The paucity of solar technicians and the high cost mean that uptake is slow. But Nigeria’s tropical climate, with an average of 5-7 hours of daily sunlight, makes solar alternatives viable here.

In August of last year, I decided to move to an off-campus apartment. My search took me to a building with a 5KVA solar unit installed; it was my first time seeing a large-scale solar unit. It solidified my interest in the building, and I ended up moving in. I’d already been aware of the small solar units marketed by MTN and Lumos partnership, which a lot of students use, though they cost a ton at ₦240,000 ($570.21). The company offers a monthly payment plan of about ₦6000 ($14.26), and I had resolved to buy one when I decided to leave the on-campus residence and its strictly regimented, diesel-fueled power supply. However, this building with its installed unit fell into my lap. This was unheard of, so much so that the building was named ‘Ile Solar’ in the neighbourhood.

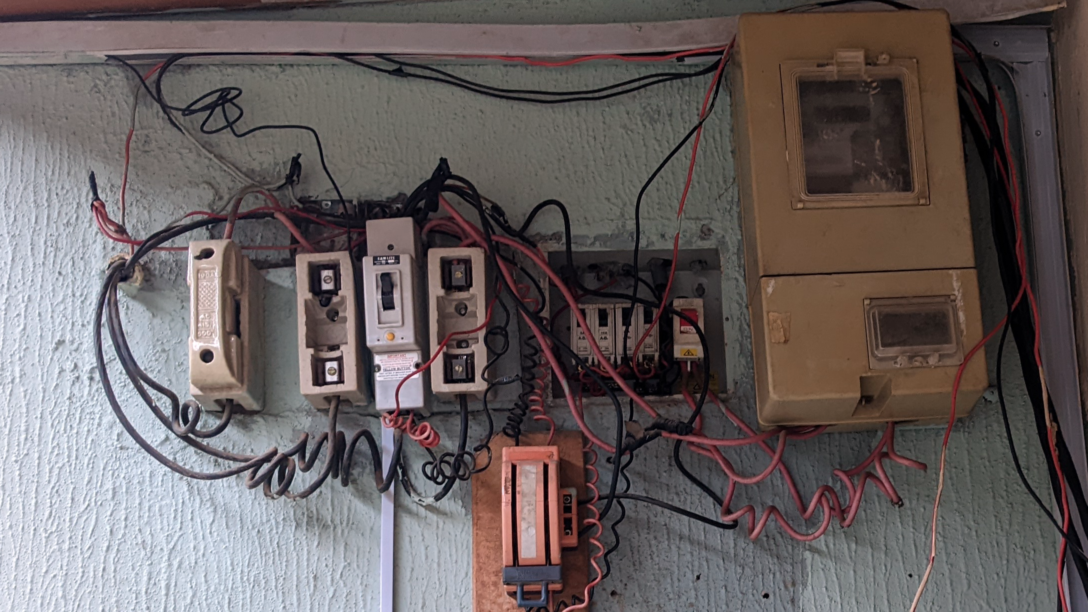

photo courtesy of the author

photo courtesy of the authorThe landlord only rented the place out to college students, and did (and still does) everything possible to make it a comfortable place to live, with overhead fans (uncommon in apartments like this), a reading room, and a large generator to power a water pump from the two wells. It was here that I unlearned the anxiety of expecting power to go off in the middle of a task. With the irregular hours I keep as a medical student and a writer, it was a dream come true to have near-constant electricity.

However, like many other places globally, Nigeria is increasingly faced with the complications of climate change: encroaching deserts in the North, and rising sea levels and increased flooding in the South. With the incessant rains and thunderstorms recently, solar panels are being affected by lightning. The solar panels are mounted on the rooftop and connected to the inverter and batteries, an easy target. The inverter in my house was blasted recently, and there we were, plunged into darkness. Although the houseowner paid for it to be fixed, at a significant cost to himself, we had to wait for the thunderstorms to die down before the inverter could be repaired, and our building was dark for about three months. During that time, I got a personal unit installed in my apartment.

The government appears to be recognizing that individuals should be encouraged to generate their own power. Last month, the Senate passed a bill allowing states and private individuals to generate electricity for themselves, although it will still require an executive order for implementation. With its potential to attract more investors in the power sector, it’s to be hoped that this legislation will help improve access to power for many Nigerians.

The last time I had to go to my parents’ for a visit, I sent a message on the family group page asking how the power situation was. The response came from my sister, “Oh, it’s been good for the past few days”. When I got home, I realized this meant that the power comes on for about four hours in a day, and most times even this was overnight. As someone who lives with almost-regular electricity now, it was a real struggle trying to adapt back.

I’m planning a weekend trip home soon, and this is my biggest worry.

Jo Naylor [CC BY 2.0] via Flickr

Jo Naylor [CC BY 2.0] via Flickr