NOVEMBER 7, 2022

Terra firma were the words sloshing around my sleep-deprived brain as I stepped onto the waiting vaporetto. It was a prayer and an invocation. For the better part of 12 hours I had been squeezed into a narrow seat aboard a Boeing 777, my economy class ticket affording me little more than a right of passage. Reason dictated it must have been my muscles—human, fallible—that were weakened. While my body, which moved to its own logic, insisted it was what lay beneath my feet that needed steadying. A bright, full moon shone in the night sky; the waters of the lagoon were inky black. Our boat gave a gentle wobble every time it took in another passenger.

Then a sudden jerk. The motor sputtered into action, and we floated away from the dock. Faint lights glittered in the far distances. But it was darkness that grew as the boat drove on. The map in my hand told me we would pass the island of Murano, then approach Venice from the Cannaregio, the sestieri, or district, of the Venetian ghetto, dense residential housing and vèneto, the regional dialect.

Refreshed by the wind and cool water mist, I wondered if my earlier wish for firm ground was a false hope. If it wouldn’t be better to stay adrift forever in this cold, ancient water, held steady by the promise of Venice. Desire could be its own reward.

On the plane I had reread American poet Henri Cole’s memoir Orphic Paris. Its epigraph, a quote from Paul Valéry, stayed in my mind: “A man alone is in bad company.” I wanted to rewrite it to say, “A mother alone is very, very happy.” Because here I was, suspended between me twelve hours ago, a mother happily at home with her children, and me half an hour from now, a woman happily away from her children. I was a mother alone and doubly happy.

The driver kept us on course, gratias Deo, and soon we were coasting down the Grand Canal. One by one, the opulent palazzos came into view. Built by Venice’s first families to showcase their vast wealth, many have since been converted into public institutions. Like eager ghosts, memories from my previous visits flooded my brain: lackluster video works at the Prada Foundation, housed in Ca’ Corner della Regina; masterpieces of Flemish painting by Jan Van Eyck at Galleria Giorgio Franchetti alla Ca’ d’Oro; Damien Hirst playing his preferred role of l’enfant terrible of contemporary art by conjuring imaginary shipwrecked treasures belonging to a fictional freed slave, Aulus Calidius Amotan, at Palazzo Grassi and Punta della Dogana, the twin sites of the Pinault Collection; and the gate by Claire Falkenstein to the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, jewel-like pieces of glass encased in intricate ironwork, firmly shut in my face on a rainy Tuesday morning. Venice was the prototypical playground of the ultra-rich, but it opened its splendors to plebes, on the right day.

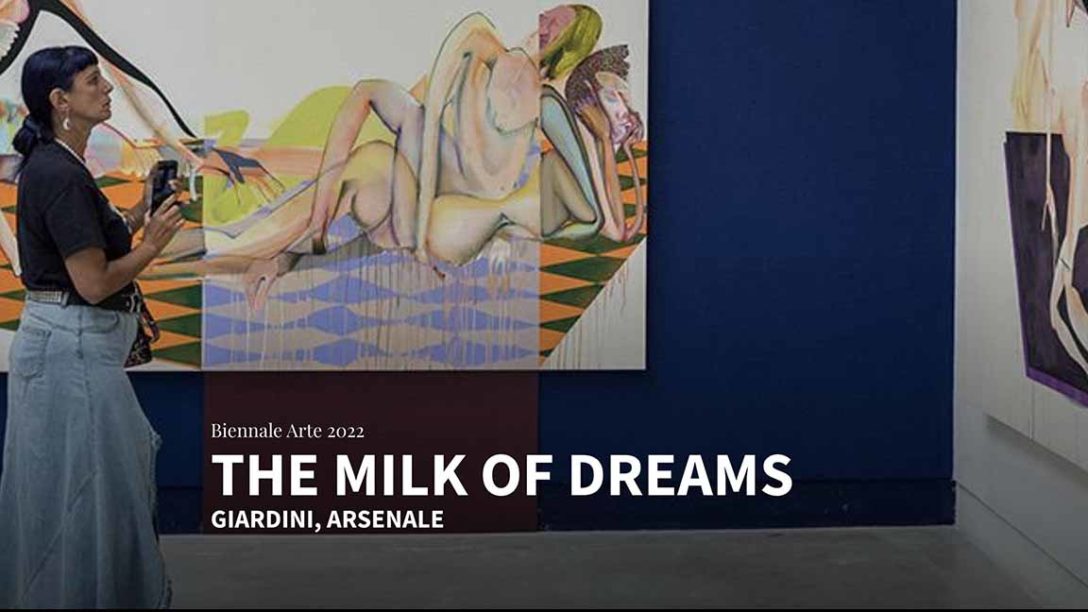

The purpose of my trip shifted back into view. I wasn’t just here to be alone. I also had an identity as “writer.” I was in Venice to attend the Biennale Arte, the latest of the international exhibitions that sometimes succeeded at summarizing and anticipating the directions of contemporary art. The title of this year’s exhibition was The Milk of Dreams. It was drawn from a book by the British-Mexican surrealist painter and novelist Leonora Carrington, who made up fantastical stories to entertain and educate her children. Carrington, another woman of multiple identities: surrealist, painter, novelist, mother, immigrant.

I heard the driver call out my stop. I searched in my bag for the written directions to my hotel. I was ready to go back ashore, to test again the firmness of my footing. There would be so much to see in the morning, and the days after.

Thank you for reading POPULA! Add your email here to receive our newsletter!