VENICE — I ARRIVED at the Palazzo Grassi on a Wednesday afternoon knowing very little about the exhibition I was about to see: open-end by Marlene Dumas.

Owned and operated by the Pinault Collection, Palazzo Grassi is as close to a white box gallery as one can get in Venice. The building, designed by Giorgio Masari and completed in 1772, was the largest and last palazzo built along Venice’s Grand Canal. Its restoration, done sensitively by Japanese architect Tadao Ando, kept intact the building’s exterior of classical proportions, its frescoes, Baroque ceiling decorations, and surfaces of rare marbles. Ando’s starkly white rooms provide a blank canvas for showing art, while creating lines of demarcation that accentuated the palazzo’s innate grandeur. Simply being in the building made it easier to believe in art as a noble pursuit, even in times of chaos.

I was less moved by Dumas herself. Born in Cape Town, South Africa, and now based in Amsterdam, Dumas is nearly 70 years old and exhibits widely in Europe, with a large-scale solo show at MoMA and Los Angeles MoCA under her belt. I must have seen her works before, somewhere, but they had not made an impression.

Then there was the Pinault Collection. Founded by François Pinault, the collection managed the art holdings of the Pinault family, whose fortune derived from the luxury-goods conglomerate Kering (think Gucci, Yves Saint Laurent, Balenciaga) and the family’s holding company, Artémis, which controlled the auction house Christie’s, among other investments. The taste of the rich was the art market, which shaped what society at large considered to be “culture” and “art.” So if the Pinaults believed an artist was worthwhile, then attention must be paid.

That’s how it was at the Biennale sometimes. With more than one hundred exhibitions happening at the same time, the decision to prioritize one over another often boiled down to just the known quantities: the artist, the building, or the money. Two out of three wasn’t so bad.

open-end is laid out over the second and third floors of the Grassi, spanning 33 rooms. The first room immediately shows Dumas’ fixations as a painter. Two paintings and a small drawing are hung at the center of the three walls. Their titles: D-rection (1999), Turkish Girl (1999); About Heaven (2001). Their subjects: a young man viewed from the side, looking down at his erect penis; a woman on her back, face leaning toward the viewer, holding up her naked legs—where the thighs meet, a line of dark paint suggests an exposed vulva; two blobs of diluted ink and a few connecting lines form the upturned buttocks and bare legs of a crouched woman seen from behind.

Next to the ink drawing, a handwritten poem by Dumas:

“About

Heaven

If death

Is a womb

then heaven

is a body without fear

that invites one

to enter from

any side

one pleases

and just for a while

Time doesn’t matter.”

There are no wall labels. Instead, a printed booklet with texts co-written by Dumas and her studio manager Jolie van Leeuwen, is provided to the visitor. I read in it that the two paintings are part of a series, MD-light (1999), for which Dumas had sourced all the images from pornographic magazines.

I suppressed the urge to laugh at the obviousness of it all. This was exactly the type of art I expected to find in the collection of rich men.

I suppressed the urge to laugh at the obviousness of it all. This was exactly the type of art I expected to find in the collection of rich men. What was already losing its emancipatory edginess in 1999—a woman! painting genitalia! and porn!—now appeared overplayed. The visual conventions and practices of pornography: provocative but unnatural poses, pubic hair grooming fads, the production of images to excite and arouse, have become just another stream in the flow of quotidian popular culture.

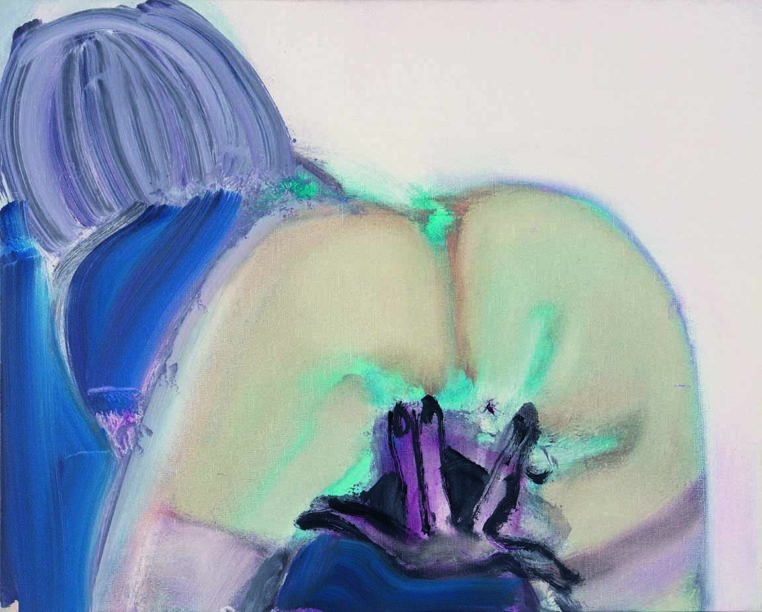

Then in the next rooms, I saw two more paintings from the same series, each showing a cropped view of a nude woman on hands and knees seen from behind. In one, Miss Pompadour (1999), the figure seems to regard the viewer, while her anus and vulva are also visible. In another, Fingers (1999), five splayed fingers are held against the woman’s mons pubis, but the figure’s head is turned away.

The bright blue lines on the body in Fingers made me pause. The painting beckons the viewer with an urgency quite apart from the frank sexuality of its subject. Dumas paints with a looseness of line, as if she is trying to record photographs imbedded in her mind before she forgets them. Her paintings don’t look “finished” in ways we are accustomed to. Her brushstrokes are sketchy and wobbly. Neither she nor her subject are fixed points, instead they are entities that move in opposite directions through time and space. In the booklet, Dumas describes Fingers as “a cold painting of a hot subject,” which struck me as perfect in its concision.

Gradually, in room after room, from painting to painting, a tension built, and two modes of expression begin to emerge. One, done in cold colors with an abstracted regard, probes the emotional depths of connection through total surrender. The other, intense and nearly black, considers the release afforded only by death. A body is a series of openings that can swallow a soul whole. Also, a body on canvas is paint—pigment and oil—smudged out, thinned, daubed, brushed, slathered on every which way.

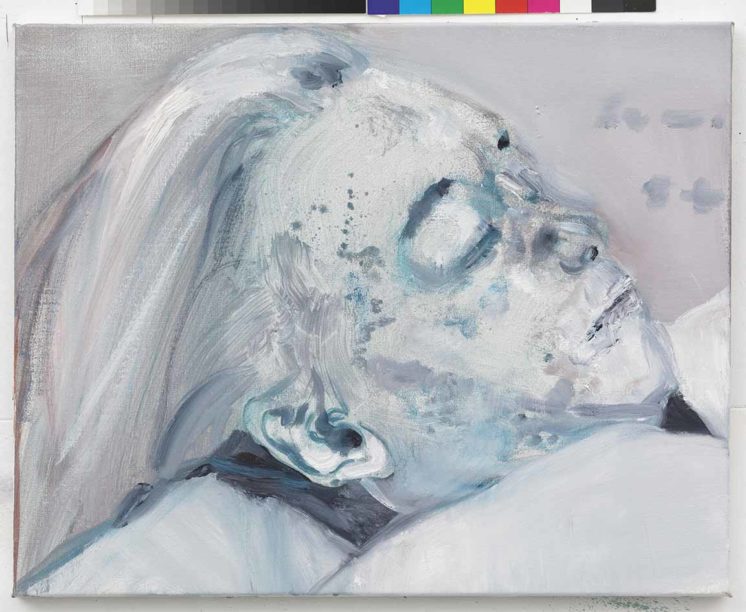

The two modes meet in Dead Marilyn (2008), which is “based on an autopsy photo published in a 1985 Dutch newspaper.” The legendary sex symbol is unrecognizable except from the title. What we see is the head of a woman with closed eyes, shadows that could be bruises covering the side of her forehead, her face, and her nose. The stiffness of her lips and jaw alerts us to something worse than sleep. Death is not pretty.

Always working from photographs, Dumas casts her visual references under a different, unnatural light, such that the paintings resemble thermal imaging—strong outlines ring bright, flat central planes. She is painting heat, both literal and metaphorical. Rendered in shades of blue, green, pink and bruised purple, the pictures aren’t so much trying to inspire desire as they are using the vocabulary of sex and desire to explore color, line, and negative space. She is more interested in the creative capabilities of brush and palette knife than in representational accuracy or in bringing about any physiological responses in the viewer. My earlier disregard for her having proven premature, I was utterly enthralled.

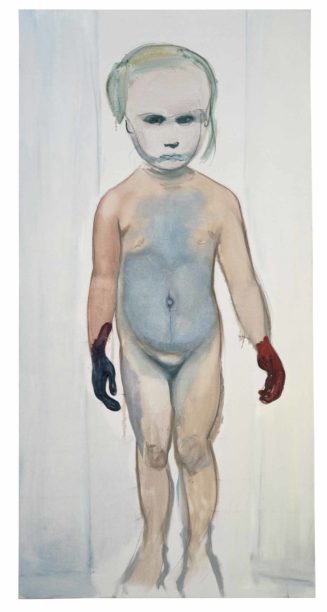

This brought me to the seventh room of the exhibition. The painting that one sees upon entry is a reclining male nude, with what could be the horizon stretched out behind him. The canvas is larger than life, at nearly ten feet long. Titled The Particularity of Nakedness (1987), its subject is the painter Jan Andriesse, who was Dumas’ lover and life partner. Andriesse died in 2021. On the opposite wall is Die Baba [The Baby] (1985), a portrait of Dumas’ older brother Pieter, based on a picture from when he was a baby. In a short film accompanying the exhibition, Dumas talks about the important role Pieter’s activism played in her understanding of the injustice and evil of apartheid in South Africa. Pieter has been in ill health for some time now. The other two paintings in the room are Eden (2020), a portrait of Dumas’ grandson at age two; and The Painter (1994), a portrait of Helena, Dumas’ daughter, as a child, which Dumas has also admitted is a self-portrait of sorts.

Spanning 35 years, these four works trace the progression of Dumas’ style toward an abstract figuration. By placing these four canvases together in the same room, though, Dumas is also staging a family reunion. What is no longer possible in life can still happen in art. Through the act of painting, and now exhibiting, Dumas achieves continuity and maps her lineage, creating a composite portrait of the artist as the people she most loved. This is Dumas at her most tender, at rest.

The strongest paintings in the show are on the second floor, which concludes with a series of recent, monumental works that burst with color and life. By working on a bigger and more ambitious scale, Dumas subverts expectations of what sexagenarian artists do. On the third floor, the highlights are two groups of ink drawings that show Dumas working quickly and inventively. Of the two, my favorite are the illustrations Dumas made for the Dutch translation of Shakespeare’s prose poem, Venus and Adonis. Dumas’ drawings pair perfectly with the poem, which tells a tale of lust, beauty, unrequited love, and heroic death, all subjects that Dumas has excelled at depicting.

The last room of the exhibition is Room 33, which has just a single painting: Persona (2020). Here, Dumas takes her characteristically loose and rubbed out brushstrokes to the extreme, creating an image that seems to be emerging and receding at the same time. The source image is “a photograph of a plaster copy of a grieving mask-like head”, one of several versions that the sculptor Auguste Rodin had made for his Gates of Hell (1880–1917). Death, yes, but there remains the hope for resurrection.

Heading down the stairs I saw Kissed (2018), the first painting of the exhibition. It is diminutive in size and easy to miss, and I only gave it a glancing look on my way upstairs. Now I stayed and looked again. At the center is a faint rectangle of smudgy sky-blue. Brusquely drawn strokes of maroon and black form a contrasting shape. Up close, the seams between the colors fuse into an outline, and then inch by inch, the painting’s subject—the kiss—reveals itself. It is a tense painting about an eternal moment. Then, with just an isthmus of manganese blue near the lips, Dumas pushes the emotions beyond the lovely, into the dark realities of passion—erosion, diffusion, a blurring of boundaries.

I remembered a man I once loved so desperately I begged him for pain. But we never kissed. I’m not sure he even remembers my name. I felt spent, or too full of pathos and eros perhaps.

I walked down the grand staircase and out into the Venetian evening. Rectangles of light poured onto the narrow streets from cafés, shops, bars, and the restaurants. The city was alive with laughter and merriment. The world is vast. Our lives are brief. Et puis, et puis encore? Baudelaire’s question from “The Voyage” rang in my mind: And then? And what then?

Thank you for reading POPULA! Add your email here to receive our newsletter!