THE BIENNALE WAS weighing on me. Fresh in my mind was a plant-choked room bursting with the sounds of sirens. The room contained an artwork—was an artwork—by the Nigerian-American artist and poet Precious Okoyomon, titled To See the Earth before the End of the World (2022). Planned out like an indoor garden, the installation had curving pathways, artificial streams, and even live butterflies. Kudzu and sugarcane were planted in April, before the Biennale opened. Now seven months later, nearing the end of the exhibition, the plants have thrived and grown thick over mounds of dirt.

This was the last artwork in the Arsenale portion of the Biennale’s main exhibition, “The Milk of Dreams.” My eyes were tired from watching idea-laden videos, and the undulating layers of green offered a respite. The limited ventilation and lack of natural sunlight made the air feel heavy, still I was charmed by the overgrown wildness. Then I heard it, the sound. What at first resembled recordings of birdsong quickly morphed into a whistle; the pitch and volume climbed steadily higher and louder, until it was a blaring siren. In just a few minutes, the room went from potential refuge to a hazard. The message was clear: heed the warnings of ecological collapse; do something before it’s too late.

It took me a minute to refocus on the laminated paper in my hands again. The menu had been helpfully translated from Italian into French, German, and English. It was evening, but much too early for dinner. I had watched the sunset from the docks near Saint Mark’s Square, taking in the sounds of wakes hitting against the stone foundation and the gondolas. Across the water, the island of San Giorgio Maggiore and its Palladian basilica seemed to float on alternating ribbons of carmine and orange. I had picked a street at random and it brought me here, to this nearly empty restaurant. I smoothed the tablecloth with my hands like I did at home, but instead of my daughter asking me what utensils we would need for dinner, all I heard was the clicking of silverware against porcelain plates at the next table. A family of tired tourists sat in near silence, hungrily cutting into their pizzas. I stood up, thanked the host, and hurried away.

A feeling of having made too many wrong choices gnawed at me. Food had always been an afterthought for me at the Biennale. First, there was the art, galleries and rooms of pigment, clay, bronze, wool, glass, dirt, plants, plastic, bits and bytes that filled the mind yet left the hands unsullied. Then, habits from my youth that encouraged thinking and arguing about the art—espresso, wine, a borrowed cigarette or three. I relished the exhilarating unsteadiness as I stumbled away from the Arsenale or Giardini after a long day, my body but a vestige trailing after my engorged brain. And eventually, a panini or slice of pizza ingested purely for sustenance.

On my last trip to Venice, though, I had a complete, singular meal. It was a perfect evening in July. There wasn’t a menu. The host chose the wines and brought out whatever the kitchen was cooking until we were the last table left on the terrace. In between the first and second seafood course I ate a plate of pillowy, cloud-like gnocchi that has haunted my taste buds ever since. I ambled back to my hotel smoking a bummed Zhongnanhai cigarette, its scent bringing me back to being 22 and late night walks down the alleyways of Beijing.

I couldn’t remember the restaurant’s name. My very foggy memory conjured up a tidy, stone-paved square with a tranquil fountain, somewhere between Teatro la Fenice, the famed opera house, and Palazzo Fortuny, of the luxury fabric purveyor. So I kept walking, past the shops of San Marco, then over the bridge in front of the Chiesa di San Moisè, down a narrow alley whose name changed at every bend. Striding up the stone steps of another bridge, dark green waters glimmering under lights from open windows, I started to think it looked familiar, as if I had stepped back into that night from five years ago. Then the alleyway ended. In front of me was a busy street lined with shops and noisy restaurants. I was just following the flow of the city, not an intuitive path etched in my memory. The thread was lost.

Looking back at the way I came, I spotted a sign for Trattoria vini da “Arturo.” The exterior was framed in tongue-and-groove panels of weathered wood. I could see through its white curtain that the interior was small and narrow, like a ship. Two tables were occupied and the restaurant didn’t have many more. There was no fountain, no shade tree, no terrace. But I was drawn to its feeling of quiet dignity borne of agedness. The waiter saw me peering in from the outside and smiled, then he gave me a nod of invitation. I had been following a feeling, not a set of directions, and here was a refuge radiating warmth and hospitality.

Inside, I was guided to a bench seat. I spoke some broken Italian to say I was dining solo, alone. Then I heard the waiter chat with the other diners, all Americans, in perfect English. There was no point in pretending otherwise; I was a tourist in search of dinner. I surprised myself then. Instead of thoughtfully ordering, I told the waiter about my long day, my abbreviated search for the dreamy gnocchi, and finally my hunger.

The waiter responded with a benevolent smile. “Everything here is good,” he said. He brought me a small carafe of red wine and a bread basket. He wasn’t going to make my choices for me; I would have to decide for myself. With an assist from a few well-timed nods, I settled on a simple meal of the daily salads and spaghetti alla siciliana.

An elderly man strode over to a cabinet near the front door and started assembling my antipasti. His large frame fit the spaces between the tables completely, like a puzzle piece nestling into place. He gently set down on my table a plate composed of mushrooms, eggplant, and artichokes. Of the three, the eggplant was the standout, a single perfectly cooked slice, topped with jammy onion, pine nuts, and marinated raisins. It was finished off with a drizzle of very tart dressing, which cut through the sweetness and allowed each component to maintain its own flavor. From taste to texture, it was simple yet unexpected. I wiped my plate clean with the bread.

The spaghetti arrived quickly after, steam still rising from the curls of noodles. Lately I had been working to calibrate my sense of what cooked pasta should taste like, alternating as I did between two early food memories: slurpable hand-made noodles from my grandmother’s kitchen in Xi’an, and the paste-like contents from cans of Chef Boyardee, which 1990s advertising had convinced me was a highly desired food of American children.

I gathered some pasta with my fork, making sure to get enough sauce for the first bite. The spaghetti crunched between my teeth. I picked up a few different strands and tried again. Same. This time the pasta splintered into shards. I had never eaten pasta so undercooked. I drank the rest of my wine and took one more bite. Al dente to me meant a noodle that flattened with the bite, then clung to my teeth for just a moment before letting go, making way for the sauce to mix in and coat my tongue. I could tolerate more chew, but this was just eating sticks. I had read about the concept of pasta al chiodo, to the nail, in foodie blogs. I had believed it was more of an expression, like “hardcore,” and at worst an affectation. Yet here it was, spaghetti that had been dipped in hot water, served by an old-school Venetian trattoria, daring me to eat it.

I waved to the waiter. It seemed like a very rude thing for a tourist to do, but I had to know why I was eating undercooked food. Soon he appeared at my tableside with the wine bottle and refilled my now empty carafe. Before I could gather up my nerve to question the pasta’s doneness, he handed me a photo album, then walked away.

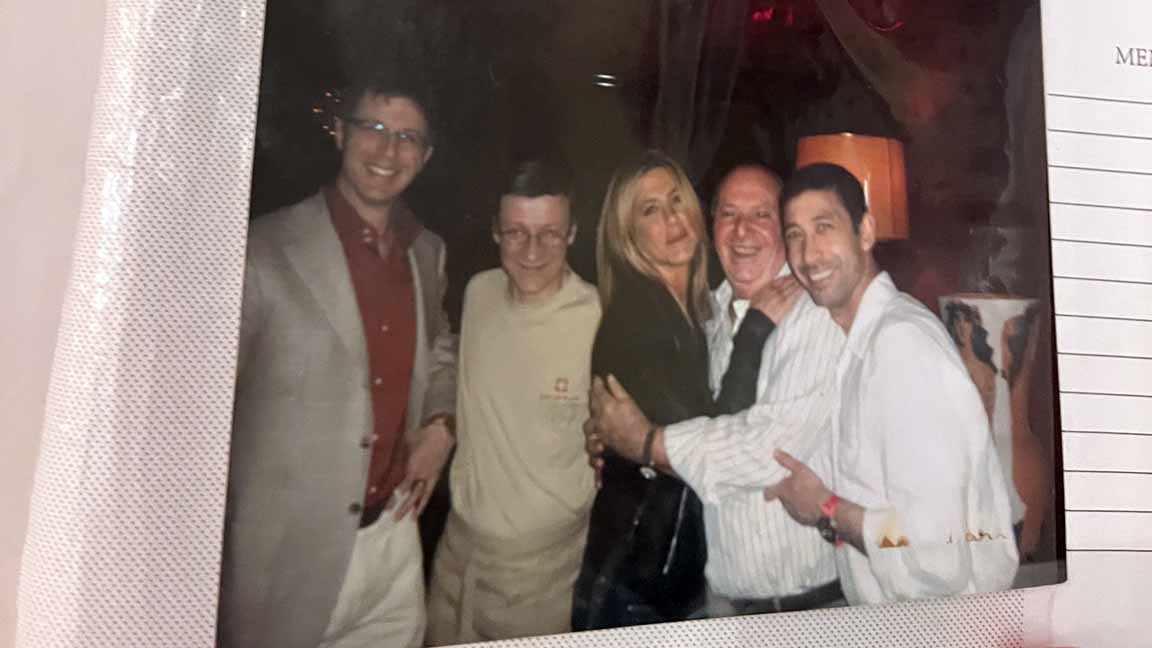

I pushed my bowl aside for a moment and looked at the photos. Here was Jennifer Aniston. Then a group photo with Barbra Streisand at the center. Younger versions of Tobey Maguire, Reese Witherspoon, and Paul Walker sat around a table, smiling for the camera. In each photo were also the elderly man and my waiter. Everyone looked happy and relaxed, like people who had enjoyed a meal together. I wondered if the pasta served was as rigid as what I was eating.

I gave myself and the pasta one more chance. By now the noodles had softened, but only slightly. The sauce, on the other hand, was excellent—silky yet sandy, like a spicy tomato that was freshly picked from the vine, and then instantly disintegrated in my bowl. It was very edible. So I did the polite thing and ate it all. When the waiter came back to explain with pride that the photos were taken in Los Angeles, at private dinners cooked at the house of movie producer Joel Silver, and the Chef himself, Ernesto Ballarin, was a distant relation of the Agnelli family of Fiat fortune, I found my opening.

I asked him, casually, like this was something I always said at the end of a meal, “How long do you cook the spaghetti?”

“Six minutes,” he said. “Always.”

Thank you for reading POPULA! Add your email here to receive our newsletter!