WHO IS RESPONSIBLE for protecting the American public from the coronavirus pandemic? Two days before millions of people sat around the table with their families and friends to eat Thanksgiving dinner, Dr. Anthony Fauci, in his last weeks as the United States’ pandemic czar, issued an impassioned plea for people to take care of themselves.

“Please, for your own safety, for that of your family, get your updated COVID-19 shot as soon as you’re eligible to protect yourself, your family, and your community,” he said. “I urge you to visit Vaccines.gov to find a location where you can easily get an updated vaccine. And please do it as soon as possible.”

Fauci’s request seemed simple enough. Everyone is eligible for a COVID-19 vaccine now. They’re widely available and, for the time being, free to anyone who wants it. But uptake has been low for the bivalent booster vaccines that were approved for emergency use in September. Only 17.7 percent of Americans over 18 have received one.

The week after Thanksgiving, more than 35,000 people were hospitalized for Covid, according to data from the Washington Post. A similar pattern has followed the Christmas holiday. On Dec. 26, just over 41,300 people were hospitalized, with that slowly trending upward before a slight drop to 39,968 on Jan. 3. Both upticks, which followed a calm fall season, were exactly what experts predicted.

As the United States moves through winter toward the second anniversary of the arrival of the vaccines, it’s clear that the official strategy of encouraging people to individually choose to get vaccinated has not met its own stated aims. The coronavirus is still engaged with the country, even as the country is disengaged from the coronavirus response. Individual choice, it turns out, is no answer to a collective problem.

How has the strategy gone wrong? For starters, not everyone has the same choices available to them. A December study laid out “high-impact” factors that prevented people from getting boosted: vaccination sites in rural communities are only sparsely available, which affects the decision to get one if the closest clinic is hours away. People whose ability to speak English is limited also have difficulty finding adequate care and can be put off by the process of doing so. And people without health insurance are less likely to seek boosters. (It’s, again, not clear when boosters will stop being free for everyone.)

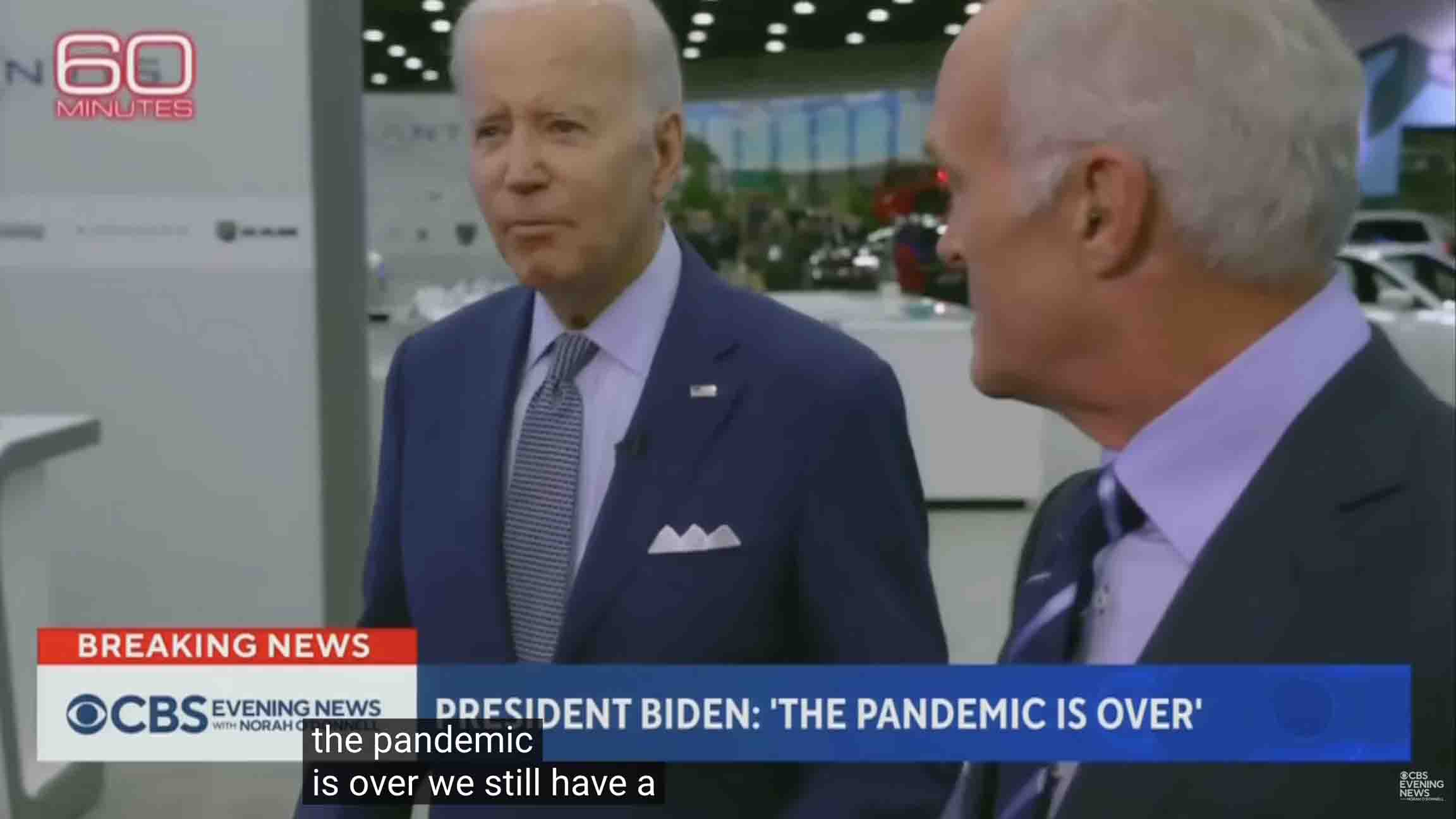

And people can’t choose things if they don’t know those things are there to choose. A September poll from the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 83 percent of Americans were unaware that they were eligible for the updated boosters or that the CDC had recommended everyone receive it. For people who were eligible but were getting over a recent infection, the guidelines were unclear as to whether they should get boosted as soon their symptoms cleared, three months later, or not at all. Adding to the confusion, COVID rates were low in September. Then, President Joe Biden declared that the pandemic was over—a clear-sounding proclamation atop the confusing official statements.

How urgent could it be to get vaccinated against something that was over? “When we first opened up appointments for people to get boosters, they filled up pretty quickly. Then we noticed a lot of people were canceling them and rescheduling for later in the fall,” said James Conway, a physician specializing in pediatric infectious disease at the University of Wisconsin. “When we started asking about it, the message a lot of them thought they were hearing was that they should hold off until it was closer to the holidays. When there’s going to be more travel and more people congregating.”

It was never communicated that, with vaccines, you don’t want to miss any opportunities. Canceling vaccine appointments, Conway believes, led to some people forgetting to set up their next appointment. Or, more concerning, people thought that the medical establishment was conveying that vaccinations weren’t necessary.

Even people who still seek vaccines have trouble actually finding access to them. Scheduling an appointment is awful, even for the tech-savvy who live in major cities with densely available medical resources. Many jurisdictions failed to do a booster rollout that matched the mass push for the original vaccine series. Staffing shortages mean vaccine providers can’t offer as many appointments. This problem is compounded by swamped hospitals and clinics simultaneously handling the respiratory tripledemic and still catching up on the medical care delayed during the pandemic.

So what room is available for personal choice when that individual’s decision can have community-wide consequences? And how can public health function properly in a society where the nostrum of choice is deemed more important than community well-being?

None of our options exist in a vacuum. As much as everyone would like to think we make our decisions based wholly on our free will, we don’t. Our decision-making is based heavily on the options accessible to us, the communities in which we live, the norms of those communities, our race, gender, and more.

Before the country’s grim “Covid contract,” as Adam Serwer called the willingness to let Black and brown workers die to keep the economy going, became clear in April 2020, it appeared as if we might see a sustained effort to “stop the spread,” even if the presidential administration at the time was reluctant. A national emergency was declared, people were asked to stay home and give the government time to devise an action plan.

Once it became evident that Black and brown Americans were disproportionately dying, though, the language changed. Conservative news hosts began venting their frustrations with social distancing and masking, likening them to infringements on personal freedom.

Over the months and years that followed, individual freedom and choice became the bipartisan framework for responding to the pandemic. The Trump administration’s wishful message that the virus would go away on its own gave way to the Biden administration building its pandemic strategy around vaccination—reducing the collective crisis to a matter of individual actions, and personal responsibility.

In Biden’s own words: “Here’s the bottom line: Virtually every Covid death in America is preventable—virtually everyone. Almost everyone who will die from Covid this year will not be up to date on their shots, or they will not have taken Paxlovid when they got sick.”

“Your health is in your hands. If you are unvaccinated, please get vaccinated as soon as you can to decrease your risk to #COVID19,” CDC Director Rachel Walensky tweeted in May of 2021. “If you choose not to be vaccinated, continue to wear a mask and practice all mitigation strategies to protect yourself from the virus.” Yet since then, Walensky has routinely said masking is a personal choice.

These are the people and institutions responsible for providing clear, official guidelines. In that light, talking about other people’s responsibilities is a way of avoiding their own.

“This idea of personal choice has always existed [in public health],” said Dr. Jorge Caballero, a medical doctor, and co-founder of Coders Against COVID, a collaborative that complies COVID-19 data for public health agencies. “The idea behind public health messaging is that you recognize that there’s a lot of carrots that you can offer to get people to do the right thing. But what’s been odd so far in the pandemic is this willingness at the national level and then down at the state and trickling down to the local level to abandon the emphasis on community health in favor of appealing to the individual directly—which obviously isn’t working.”

The decline of masking demonstrated how individualistic messaging eroded community standards. In 2020, before vaccines were available, the only federal mask mandate was for people on public transportation, but CDC officials made it clear that masking was, at that moment, the best option after social distancing. The general public, for the most part, agreed. People were kicked out of stores like Costco, Trader Joe’s, and Walmart for not masking—even as they complained that it was their right to refuse. By July 2020, statewide mask mandates were active in 28 states and several major cities in states lacking orders. By August, 85 percent of adults were regularly masking.

In 2021, as the vaccine requirements expanded to include more people and orders mandating masks expired, masking was still widely accepted as a primary mitigation tactic. That May, though, the CDC loosened their recommendations to emphasize that fully vaccinated people didn’t need masks at all, on the grounds that 62 percent of Americans were vaccinated, and an uptick to 70 percent was expected in the coming months. Masking wasn’t completely thrown out; a Pew Research poll from September 2021 found that 53 percent of adults were still masking indoors, even if that was a drop from 88 percent in February.

The same data also revealed a political split. Seventy-one percent of self-identified Democrats were masking compared to 30 percent of Republicans—another huge shift from February when 83 percent of conservatives were masking up. People were still making their choices about masking based on community norms, but now they were following partisan norms rather than public-health ones.

We don’t see this phenomenon elsewhere. Despite vaccine hoarding from wealthier nations, seven countries in South America have fully vaccinated more than 70 percent of their population. The same applies to Cuba, Nicaragua, Panama, China, Japan, India, Iran, and to the nations outside the United States considered part of the Western world.

Even many countries with relatively limited resources have been able to commit to collective measures.

“In a lot of other countries where there is still masking or high rates of vaccination, these communities are more used to, for example, living in intergenerational households. We’re not,” said Dr. Rupali Limaye, an associate professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. “One of the issues that we really struggled with at the beginning of this pandemic was, even if you don’t want to get the vaccine, get it so that you don’t kill your grandma. It’s this idea that you’re protecting others who don’t necessarily have the same advantages that you do.” (Some countries with high rates of intergenerational homes—like most of Africa—have low vaccination rates due to vaccine inequity.)

While individualism is not unique to us, our blind faith in exceptionalism shapes the belief that community matters less than the self. And these personal decisions have consequences beyond our own bodies. Forgoing vaccination, masking, and other precautions can directly lead to the poor health and death of others—including babies, the immunocompromised, and the unvaccinated.

“When we talk about vaccines, in particular, and what people choose to do with their bodies, it’s within a context of a self-centered, very traditional individualistic American notion of ‘I’m going to look out for what’s best for me or what’s best for my family,’” said Dr. David Malebranche, an internal medicine doctor, and public health advocate.

While it is your individual decision to mask or get vaccinated, your decision provokes others to take their health into their own hands through mandates for both measures, which then pushes you to revolt and rage about your personal freedoms being infringed upon.

And don’t forget who the real villain is here. The elected officials who never pushed the importance of vaccination in a way that was relatable to people who were afraid of needles, repeating history, or a continuation of current treatment realities, as is the case for people of color in the U.S. The people in power who demanded that you listen to them without hearing your concerns—even if those worries were unfounded or based on conspiracy. And the people who then turned it back on you and affirmed that, yes, even after their utter failures to protect you, it was your own choice to save yourself.

Julia Craven is a writer covering health, wellness, and anything she thinks is cool. She’s also the brain behind Salt + Yams, a newsletter dedicated to archiving Black health modalities.

Thank you for visiting POPULA! Add your email here to receive our newsletter!