TWO LONG MAGAZINE stories about Elon Musk just came out, one in New York magazine and the other in the New York Times Magazine. Taken back to back, they made for illuminating reading. The New York story was about Musk’s chaotic and bumbling takeover of Twitter, while the Times Magazine story was about how the self-driving software in Tesla automobiles has a persistent and unfortunate habit of running into things, and how the company is getting sued about this.

Of Tesla, Inc. (TSLA on the Nasdaq), the Times Magazine wrote:

if you want a parsimonious explanation for the challenges the company faces — in the form of the lawsuits, a crashing stock price and an A.I. that still seems all too capable of catastrophic failure — you should look to its mercurial, brilliant, sophomoric chief executive.

This seemed unquestionably true in its broad outlines, but there was a real debate to be had in the adjectives. The piece kept returning to a theory that what looks like recklessness, sloppiness, or sociopathy from Musk might better be understood as a profound, all-encompassing belief in a “crude” but “coherent philosophy,” which leads him to seek “the greatest good for the greatest number of people,” according to “an ad hoc system of utilitarian ethics.”

Self-driving could, theoretically, eliminate human error on the roadways, thereby saving lives; therefore it’s worth wrecking some cars and killing some people along the way. Theoretically. But what if the person who is making these ethical calculations is not, in fact, brilliant? Not just careless with people’s lives (to say nothing of lives of the pigs being hastily vivisected to speed up work on Musk’s vaporous Neuralink brain-implant technology)—and the Times Magazine story goes into harrowing on-road detail about how unready the self-driving technology is—but legitimately, seriously thickheaded? What if there were a rapidly accumulating body of evidence that Elon Musk is an utter boob who has bluffed his way into a position of world-changing wealth and influence?

Here’s a moment from inside Twitter, from the New York magazine story:

On October 26, an engineer and mother of two — let’s call her Alicia — sat in a glass conference room in San Francisco trying to explain the details of Twitter’s tech stack to Elon Musk. He was supposed to officially buy the company in two days, and Alicia and a small group of trusted colleagues were tasked with outlining how its core infrastructure worked. But Musk, who was sitting two seats away from Alicia with his elbows propped on the table, looked sleepy. When he did talk, it was to ask questions about cost. How much does Twitter spend on data centers? Why was everything so expensive?…

Fine, she thought. If Musk wants to know about money, I’ll tell him. She launched into a technical explanation of the company’s data-center efficiency, curious to see if he would follow along. Instead, he interrupted. “I was writing C programs in the ’90s,” he said dismissively. “I understand how computers work.”

Suppose that when Elon Musk says he’s pursuing “[m]ost good for most number of people”—as the Times Magazine reported that he did in writing to a man whose son was killed in a Tesla crash, to explain why he wouldn’t take the bereaved father’s suggestions about adding safety features—he’s not expressing any sort of deeply held belief in long-term, mass-scale utilitarian ethics at all. Suppose, instead, that for Musk, “most good for most number of people” serves the same function as “I was writing C programs in the ’90s”: it’s a set of words or sounds he has learned to string together to establish that he doesn’t have to listen to what someone else is trying to say. It’s where his brain, no longer up to processing the complexity of the world, shuts off.

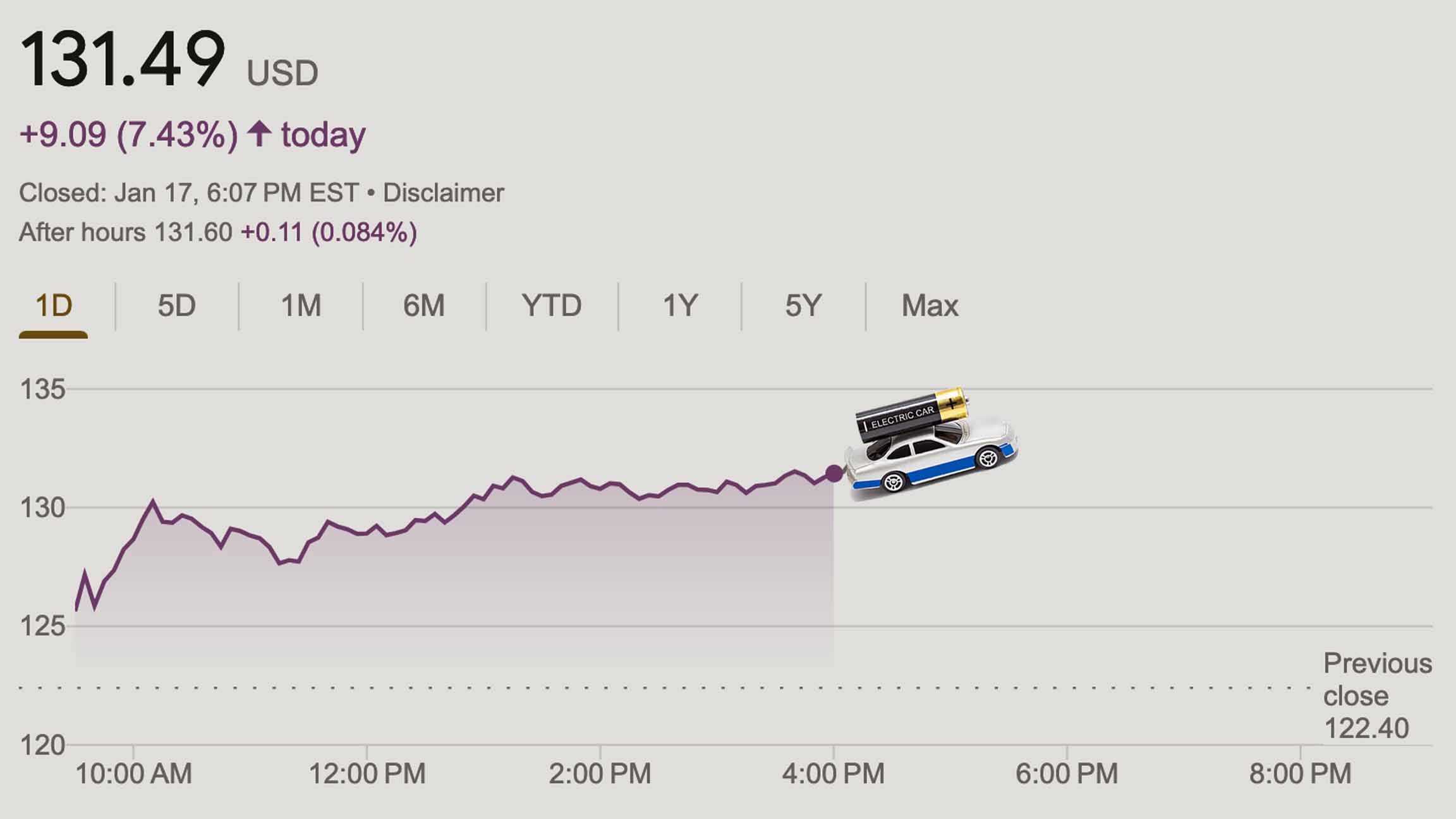

The important thing, though, is that he’s in the magazines. His new depths of buffoonery are apparently becoming background facts. And TSLA stock is resolutely climbing up again, after its months-long rout.

Last Tuesday, after gaining $10.75 in the previous week, TSLA closed at $118.85. Today, it made its way all the back up through the $120s to arrive at a closing price of $131.49.

The $12.64 that a share of TSLA gained since last Tuesday would have been enough to buy any of the following:

• One pint of opaque, lead-free gloss pottery glaze, “maple sugar” colored

• One cartridge of Valvoline multi-vehicle molybdenum disulfide–fortified gray grease (14.1 oz.)

• A used DVD of the 2004 EP Kaantaben 90 Non-Stop Dandiya (listed condition: very good)

• 100 coconut-shell-based vegan activated charcoal dietary supplement capsules (260 mg)

• One replacement starter solenoid for a 1962 Studebaker

• 18 sheets of inkjet-printable fabric transfer paper

Thank you for visiting POPULA! Add your email here to receive our newsletter!