ON APRIL 7, 1944, four years into the German occupation of France, the New York Times reported on the debut of Tricolor, “a monthly magazine devoted to the cause of French Liberation.” It was just a small announcement, with an extended quote from editor and publisher André Labarthe: “Democracy—France’s great heritage—must not only be adapted to keep pace with modern life; it must also deal with those who try to exploit its liberties only to enchain.”

I’ve had a copy of this very issue, Tricolor No. 1, for years and years, but only read it for the first time yesterday, and found the vibe to be a harrowingly familiar, uneasy mixture of “making the best of it,” forced nonchalance and absolute terror. Nearly 80 years after Labarthe wrote his editor’s note, the French—allied now with their former occupiers, plus the U.S. and nearly everybody else—are still dealing with “those who try to exploit [the liberties of democracy] only to enchain.”

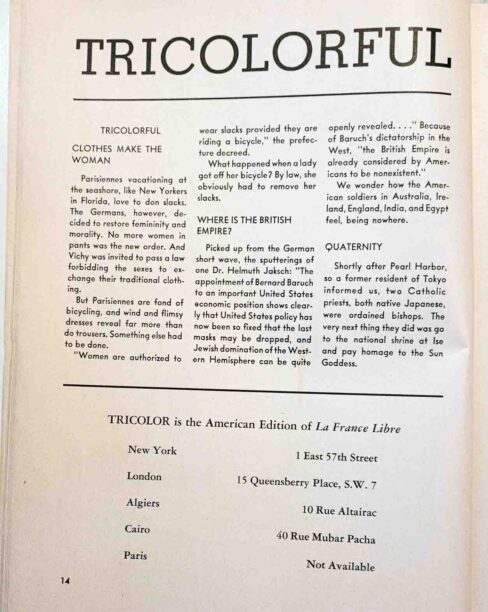

Tricolor had to be a magazine, intelligent, serious, but with a sense of humor and gaiety; it had to entertain, and inform, and raise money. So there are beguiling things to sweeten the horror, and to distract; there’s information, and calls to action, and reminders that there is more to life than war. It opens with lots and lots of pretty ads for Coty and Cartier, Van Cleef & Arpels, which give way to appeals to the 1944 Red Cross War Fund (“Let’s All Give”).

Here’s a German prisoner of war, an officer, calmly Nazplaining to his captors how a few million more Frenchmen might still need to be killed before things settle down: “I’m sorry sir, but our General Staff insists on unconditional submission. The French people must cease to exist as independent people. That constitutes a danger for Europe. But we’re not barbarians. We’ll perhaps not destroy all Frenchmen. Certain classes can subsist, once they’re in hand.”

Gee, who does that remind you of.

“Have you calculated the hatred your actions have created against you in France?” replied the interrogator, a French colonel.

It was the German’s turn to smile. “People forget so quickly. I know we shall be detested, especially if we’re not militarily successful, but we shall hide among you, learn to speak French well. We shall have your money, your paintings, your chateaux. We shall have compromised so many Frenchmen that they’ll have to help us.”

The French colonel responds, “I’ve heard all this many times before; I’ve yet to be impressed. Believe me, Captain von Klemm, if you value your life, don’t stay in this country after your armies have been driven out.”

Next up, a charmingly illustrated feature about how the ladies of occupied France are improvising fashions, making their own (adorable) shoes of wood and fabric; “two shawls equal one skirt,” “fashion demands wide belts,” and all this appears alongside accounts of Germans destroying everything as they retreat, and “the whole land is mined.”

How like our own fractured media this is, now on a global scale. The rumpus over Beyonce’s $24 million performance in Dubai; the Hindutva propaganda in RRR; the sexual politics in White Lotus 2; the Academy’s failure to give The Menu the slightest recognition (unsurprisingly, seeing how it is about them); the runaway success of Prince Harry’s memoir, the birthday wishes to Volodymyr Zelenskyy from his wife (they met when they were seventeen), and the rejoicing at the news of Leopard 2 tanks on their way to Ukraine. The pollution of the United States and the United Kingdom by these same people, by fascists, is romping along through book bannings and open displays of racism and transphobia.

The Germans came to regret their slide into fascism, made amends, rewrote their histories and revamped their education systems, and made at least some restitution for the thievings of their corrupt government, but will that reckoning ever come for the Russians, or for the far right in the U.S., India, Israel, Italy or France?

Nobody can blame people who are defending their own houses against a bunch of fascists who’ve come from who knows where to kill them and/or take their stuff. It’s so many years ago we told our Republican relatives you cannot support these people, these people are fascists, and what a lot of eye-rolling there was. But the U.S. Republicans are in cahoots with the fascists who are now in power in Russia. You can read Tricolor and see what happens when they succeed. France in 1944 was like Ukraine would be today, had the Republicans managed to steal the last U.S. presidential election.

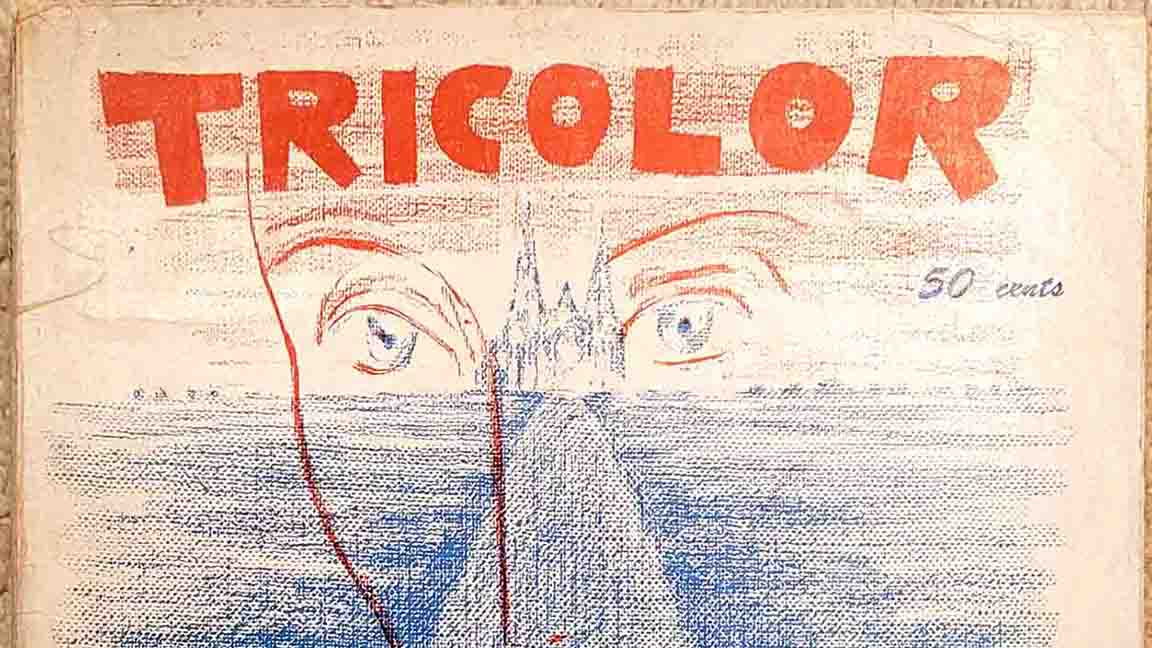

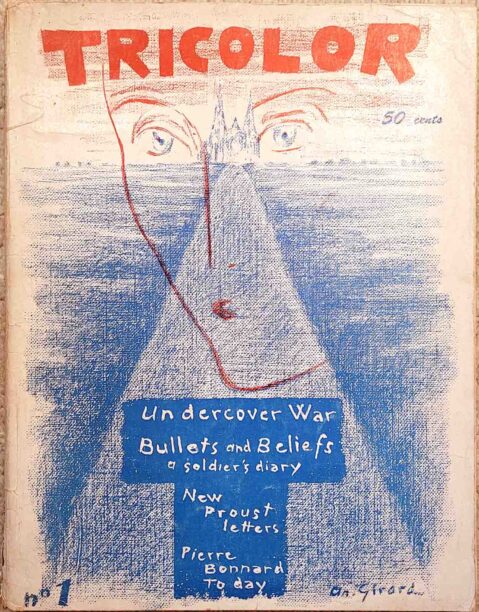

Seven by ten inches, 128pp. Cover price, 50 cents—expensive!—about $8.25 in 2023 money, according to a couple of different inflation calculators.

The wispy, evocative cover art is by André Girard, an artist, author, graphic designer and resistance organizer, codename “Carte”.

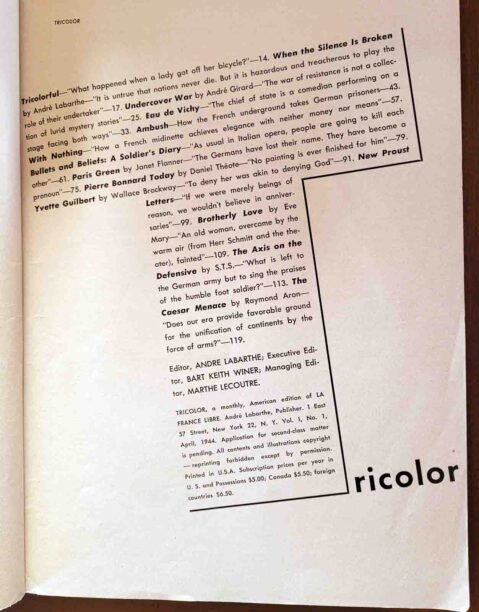

The cover stories are “Undercover War,” an excerpt from Girard’s memoir, Bataille Secrète en France; a soldier’s diary, “Bullets and Beliefs”; a selection of Proust’s recently discovered letters to Marie Nordlinger (“Has Reynaldo told you that this wicked Ruskin has forbidden his works to be translated into French, so that my poor translation will remain unpublished?”—lol what a diva he was. His translation of The Bible of Amiens, produced with a considerable assist from his mom, came out that very year).

There’s also a short interview with the painter, Pierre Bonnard, then 76 and keenly focused on peaches (“They’re amazing!’ he rejoiced to friends”). But read on a bit and you’re like, who wouldn’t have just gone into orbit, nobody could avoid going nuts in his situation:

In the winter of 1941 Bonnard had no coal and no milk. He had enough money, for he can live on little. A single drawing sold could provide his whole year’s needs. The lowest-priced Bonnard painting brings in 300,000 francs—sufficient money to last him five years. But it takes more than francs to obtain coal and milk in Petain’s France.

Many Vichy officials came to pay their respects to the painter. When he mentioned his plight, they were outraged… [he was] thereupon commissioned to paint the Marshal’s portrait.

Bonnard was stunned. “I need just two things,” he told the Vichyites, “coal and milk. As for the portrait—if Marshal Petain is a good model, I’ll paint him. But remember, if I don’t like my work I reserve the right to destroy it.”

The commission was withdrawn, sadly.

Not listed on the cover, but awesome, and chilling: “Paris Green” by Janet Flanner, with a vivid report of what it was like to live in the capital. One could imagine the same thing having happened, so very easily, in Kyiv.

What Parisians, during their first years of occupation, called verbal vengeance—the useless, civilized relief of scathing wit, of spoken contempt, of angry phrases—has long since ended. To raise French voices against the Germans contributes nothing effective now. There can be no relief in shouting or whispering “Boche,” which merely leads to prison. Today, halfway through the fourth year of national misery, Parisians call the Germans “They.” Ils ont dit. Ils ont fait. Ils sont la. The Germans have lost their name. They have become a pronoun.

The Germans truly believe that force implies intellectual superiority, that mastery infers control, that occupation results in possession. Their amazingly ingenious theories have only one flaw: they do not work.

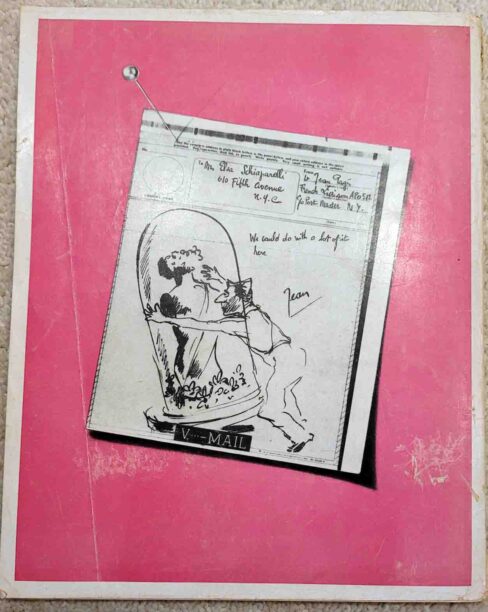

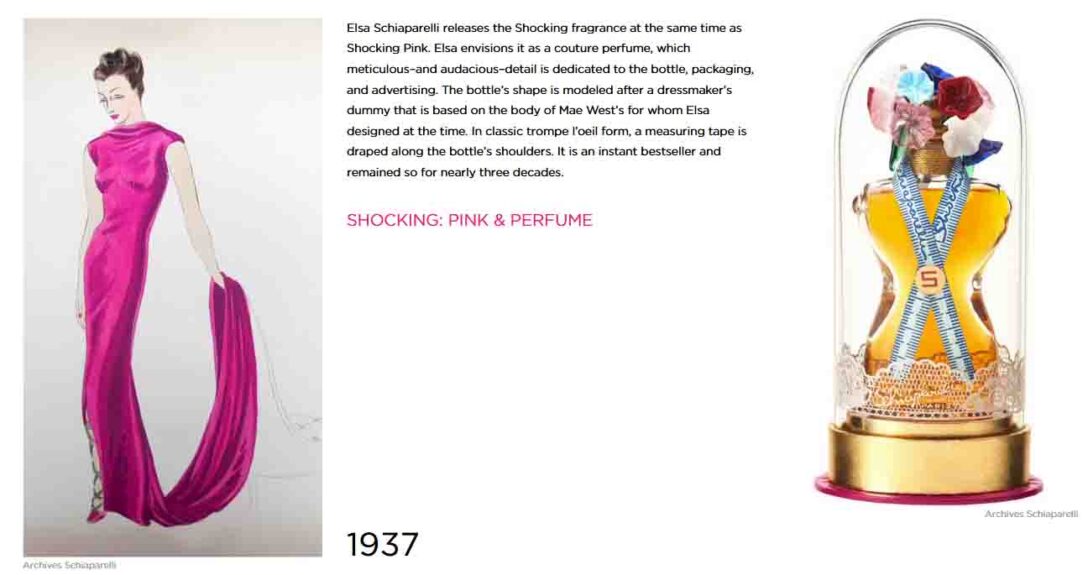

The back cover is a typically witty trompe-l’oeil Schiaparelli ad for “Shocking” perfume, depicting a telegram addressed to the designer from illustrator Jean Pagès, who was then serving in Normandy as French liaison officer to the U.S. 83rd Division. The magazine’s final page, a most fitting amalgamation of beauty, fear, a dashing joke, expressing a moment of wild, exhausted, and maybe impossible hope, like our own.

A magazine captures the world of the present and concentrates it into a few radiant pages. But as time moves beyond the moment it crystallized, it can tell you more and more. The colors, the weight and texture of the paper, the typefaces and the clothes, the books and films and music they talk about, and most of all, their makers’ ignorance of what is to come, reveal to the reader of later decades a three-dimensional version of the human story, triangulated in time. What it was really, really like—the now, seen through the long lens of what came after.

Thank you for visiting POPULA! Add your email here to receive our newsletter