THIS POST COMES TO POPULA FROM OLONGOAFRICA,

A FELLOW MEMBER OF THE BRICK HOUSE COOPERATIVE.

In late 2020, when I pulled a hamstring while playing soccer, one of my friends suggested that I take a hot shower, apply black seed oil and wrap my thigh with a piece of cloth when I get home. “It will do wonders,” he said assuredly. I suppressed laughter amid the pain I was feeling. It wasn’t my first time hearing a Somali person advising another Somali person to use black seed oil for a pain or an ailment of any kind.

Black cumin (Nigella sativa) is a flowering plant native to Asia and the Mediterranean. For more than a thousand years, the plant’s seed has been used as a medication for ailments ranging from fatigue to allergic reactions, and even more complicated diseases like asthma. But for the Somalis, it is more than that. One would be forgiven to think that they hold it sacred.

Growing up, I used to see my asthmatic uncle applying it on his chest and neck and even adding it to his tea and milk when having asthma attack. My mother, too, would try to give it to us when we had colds or even a slight fever, but my sister and I used to refuse it, because we couldn’t stand its smell. Even so, my sister and I knew it was good for some ailments. I would jokingly tell her to use it whenever she was unwell, and vice versa. Years later, in college, I saw a 4-year-old boy holding a bottle of black seed oil and licking it, and thought to myself, “this is the result of his parents giving it to him every time he felt unwell.” In almost every Somali household, the older members have black seed oil stored somewhere. Neighbours often borrow it from each other when a family member is unwell, when there is no black seed oil at home.

That day, after I pulled the hamstring, I bought a bottle of black seed oil myself, used it for a few nights as I’d been directed, and kept it on my nightstand just in case. It was the first time I had used it and, truth be told, it helped me a great deal. I was first uncomfortable with the smell, but later got used to it. One morning not long after, I heard a neighbour knocking on another neighbour’s door asking for—you guessed it—black seed oil. Her few-months-old baby was unwell, she said, and they had been unable to sleep. I was coming from the morning prayers, and I said, “I have some, let me get it for you,” when the other neighbour said she didn’t have any. And that marked the end of my first relationship with black seed oil.

This mother could have taken her child, who apparently had congestion, to the hospital, but the first thing she did in the morning instead was to look for black seed oil, to apply on the baby’s chest. Something she believed would help the baby. Such is how Somalis believe in its powers to heal!

After giving away the first black seed oil I ever bought, I thought of getting another bottle just to keep handy, even if I am not using it. I somehow keep on forgetting it; could be old age kicking in. And the one or two times I caught cold after that first encounter, I regretted not having bought some. Will I ever buy it again? Yes, I will. I will keep on restocking in the future.

That the black seed oil is held sacred by my Somali people cannot be gainsaid. Back in my hometown of Garissa, there was this Somali hawker who used to move around selling black seed oil while singing a song, which, undoubtedly, he was doing to attract his customers. It went something like this:

Dawaysaa, dawaysaa! (It treats, it treats!)

Wax walbeey dawaysaa! (It treats everything)

He went around, bottle in hand, pretending that it was the last one, and he would go on to sing:

Hal iga qaadaay hal iga qaadaay (take one from me, take one from me!)

Hal baa igu haree, hal iga qadaay (I am remaining with one, take one from me!)

He might have romanticised the black seed oil, but with or without that cajoling his stock would have sold out because for the old population in Somali towns, it is a necessity.

A tale is told of a family whose resettlement in the US almost failed, because a mother among the family members in the group to be resettled said she would not go if there wasn’t black seed oil in the US. This may have been a made-up joke, but it depicts the love Somalis, especially the old, have for black seed oil.

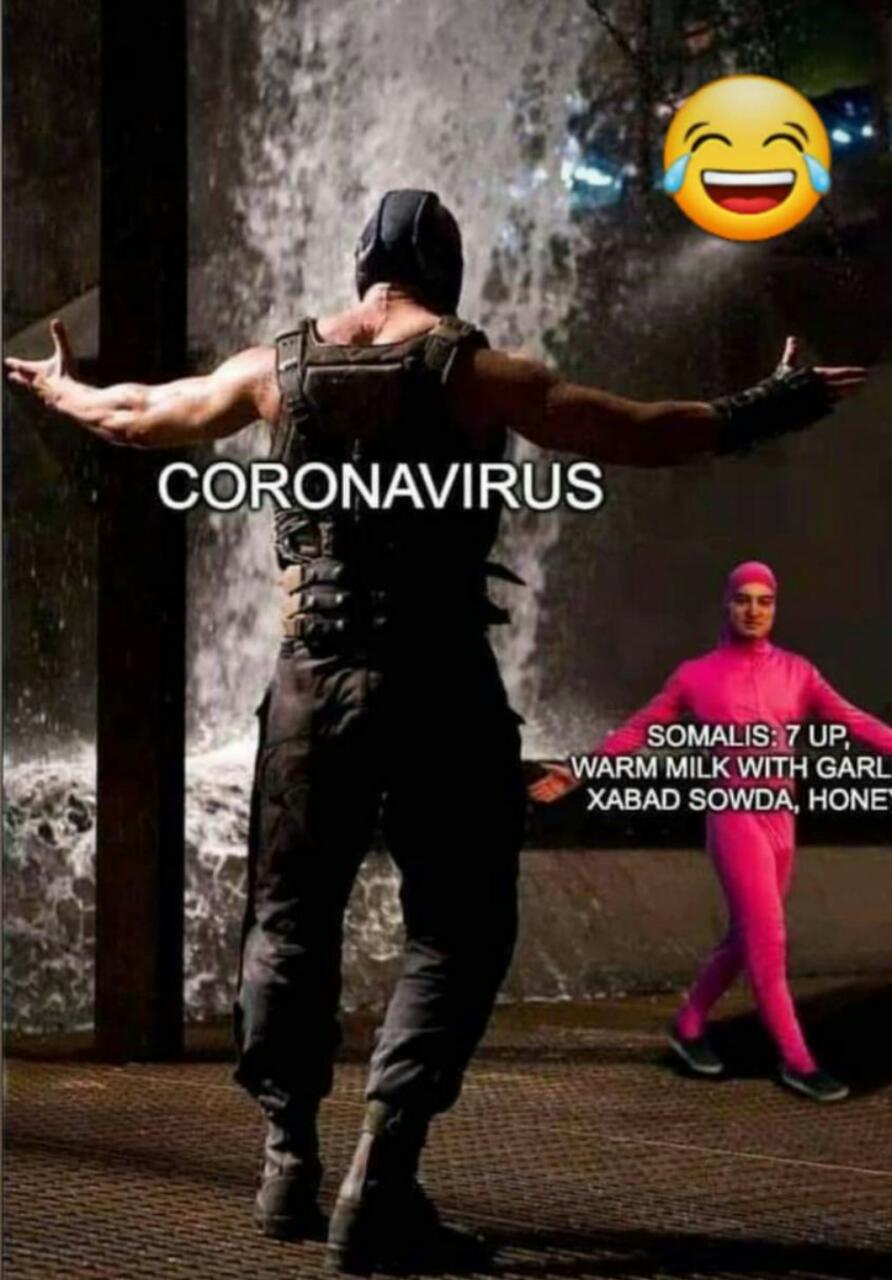

In another comical illustration of this, Somalis online created a meme during the start of the COVID-19 showing the ‘Somalis COVID-19 starter pack.’ The meme, borrowed from the movie The Dark Knight, showed Tom Hardy (the movie’s villain, Bane) as COVID-19, and Batman replaced by an all-red figure described as a concoction of black seed oil, garlic and honey coming up against him. Somalis literally throw black seed oil against any ailment and, proving the meme creator right, Somalis the world over started using home-brewed remedies for COVID-19 when the pandemic spread to the whole world.

One reason why the Muslim community at large holds black seed oil in such high regard is that it is named in one of the hadiths that Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) said it is cure for every disease except death. It is highly regarded for its ability to help the natural healing process.

In Eastleigh, the populous Somali neighbourhood in Nairobi, mixtures containing black seed oil are sold on almost every street corner. It’s sold in hundreds of shops, which, interestingly, all appear to be run by men and women in their mid-50s and above. For a young person who cannot stand the smell of old-fashioned remedies like black seed oil, fenugreek and so on, it is hard to spend more than a few minutes inside these shops. But these people know their clients.

Mohamed Jamal has a shop in the prominent Eastleigh Mall, selling a variety of items, including spices and black seed oil. The items in Jamal’s shop are all neatly packaged, unlike the other shops where they use more old-fashioned methods. Items with different labels are arranged with care on both the shelves and in the shop windows, giving the shop a touch of panache.

“What we have in this shop are things that are remedial for varieties of ailments,” he told me when I visited, in the company of my friend, who was buying sesame oil. “But the black seed is the hottest commodity here.” In every five customers he receives, he says, three will ask for black seed oil. Jamal sells four versions; three liquid ones which he says are from Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and Ethiopia, and a Vaseline-like solid one, which he says is good for relaxing muscle tension.

Jamal’s shop is a busy one. When I went back to ask him more about the herbal medicines he sells, our conversation was interrupted over and over. The packed lunch sent from his home at around 1 p.m. lay before him, still untouched, when I visited him at 4:30 p.m. His daughter was with him, and though they both wanted to eat their lunch, there was no chance. Four customers came before he could start eating: a lady bought a slimming tea, an old man in his early 60s bought black seed oil and honey for his wife whom he says has a bad flu. The other two customers were a boy in his early 20s who was sent by his aunt to buy some herbs for her aching knee joint, and two other ladies who also bought slimming tea.

A Development Studies graduate from a university in Sudan, Jamal, 44, says he was motivated to open the shop after attending numerous seminars in Khartoum about herbal supplements while he was a student there. When he came home, he started a small shop in Eastleigh’s 6th Street, but moved to this expansive shop in Eastleigh Mall after the one in 6th Street was demolished to pave way for a bigger apartment building. “I moved here, but my customers still followed me,” says Jamal, smiling.

Jamal tells me that two customers gave him the most satisfying feedback regarding the black seed oil. He says a man came to him and said that a problem with one of his knees had been forcing him to sit on a chair during prayers. Jamal gave him the Vaseline-like black seed preparation, and after a week of applying it on the knee, he was able to pray without using the chair. Another man from Canada had been exposed to snow, and one of his legs could no longer bend at the knee. He came to Nairobi and when Jamal gave him the Vaseline-like black seed oil, things changed for the better. After one month the man was able to bend his knee.

Jamal will keep on selling those herbal medicines. He knows the black seed oil will always be the most sought after, because he says everyone is now embracing it, including the youth.