Tom Scocca’s essay in New York last week, “My Unraveling,” is a matter-of-fact dissection of the failings of the US health care system, and of the casual brutality with which society treats those who fall ill; the precarity in which even the most hard-working and accomplished young professionals are expected to live, work, and raise families; and the grim state of the media industry, in which Scocca, one of the country’s most admired journalists and editors, has faced a huge amount of trouble landing a stable gig. It’s a flawless work of journalism, destined to be read and taught for years to come.

For me, though, the supreme jolt at the essay’s epicenter came in a throwaway line, buried in a list of jobs the author didn’t get (including one that disappeared in mid-application, and another whose sponsorship funding failed to materialize):

A friend of a friend let me know that another major media company was ignoring my application because it wanted someone less opinionated.

Corporate media vastly prefers (and has long preferred) to hire writers and editors who are yes-people, “team players” who can be relied upon to do (and write) as they’re told. What this means is that the best among us, the most honest and uncompromising writers we have, are effectively being cast out of the profession.

Strong, deeply held opinions, supported with facts and intelligent analysis, are exactly what we need most in these perilous times. But today, even the most highly-placed writers and editors have to tread very carefully for fear of losing their jobs. In recent months we’ve seen distinguished journalists fired (as David Velasco was, from Artforum) or forced to quit (as Jazmine Hughes was, from the New York Times) for the crime of publicly expressing solidarity with the people of Palestine. Jamie Lauren Keiles, a freelancer who resigned from his contract gig at the Times, noted that he’d been warned in a company email that “strident partisan advocacy” would jeopardize future assignments.

Strident partisans on the right, meanwhile, are openly attacking not only journalists, but academics, librarians, and teachers. In the case of journalists, the goal is to land a blow that might get a writer in trouble with editors and owners—especially at legacy media outlets like the Times, where the alleged virtues of “neutrality” and “objectivity” are so highly prized. The network of fashy creeps taking advantage of institutional weaknesses is as embarrassing as it is dangerous; the window of permissible “opinion” shifts forever to the right, to the point where congresspeople can be quoted dropping Great Replacement rhetoric but freelancers can’t tweet about Gaza for fear of becoming unhireable.

Last week, Business Insider revealed that Neri Oxman, the wife of billionaire Harvard donor and alum Bill Ackman, had plagiarized parts of her dissertation, including multiple borrowings from Wikipedia. Because Ackman had been so vehement in his demands that Harvard president Claudine Gay be fired on the grounds of academic plagiarism—Gay resigned last week—the Oxman story landed hard.

In a statement to Semafor, Business Insider’s German parent company, Axel Springer, said that “while the facts of BI’s report have not been disputed, over the past few days ‘questions have been raised about the motivation and the process leading up to the reporting.'” In other words, though Axel Springer itself admits the story is accurate, they are not committed to standing by their own editors and journalists. Business Insider’s global editor-in-chief, Nich Carlson, has evidently been called on the carpet by his bosses: “Top execs at Axel Springer seem to be worried that reports like those on Oxman last week could damage BI’s reputation in the eyes of some potential business readers.”

Ackman, meanwhile, can be found going buck wild on Twitter, where he is going way, way over 280 characters to rail at Business Insider for “going after” his wife, and accuse Business Insider editor John Cook of being an anti-Zionist. (Seeing an embarrassed and angry billionaire making trouble for journalists at work may feel… queasily familiar.)

In this atmosphere of uncertainty and fear—when you can’t be sure whether or not your organization will really have your back—it’s difficult, if not outright impossible, to do conscientious work that serves the public interest. That situation wants correcting.

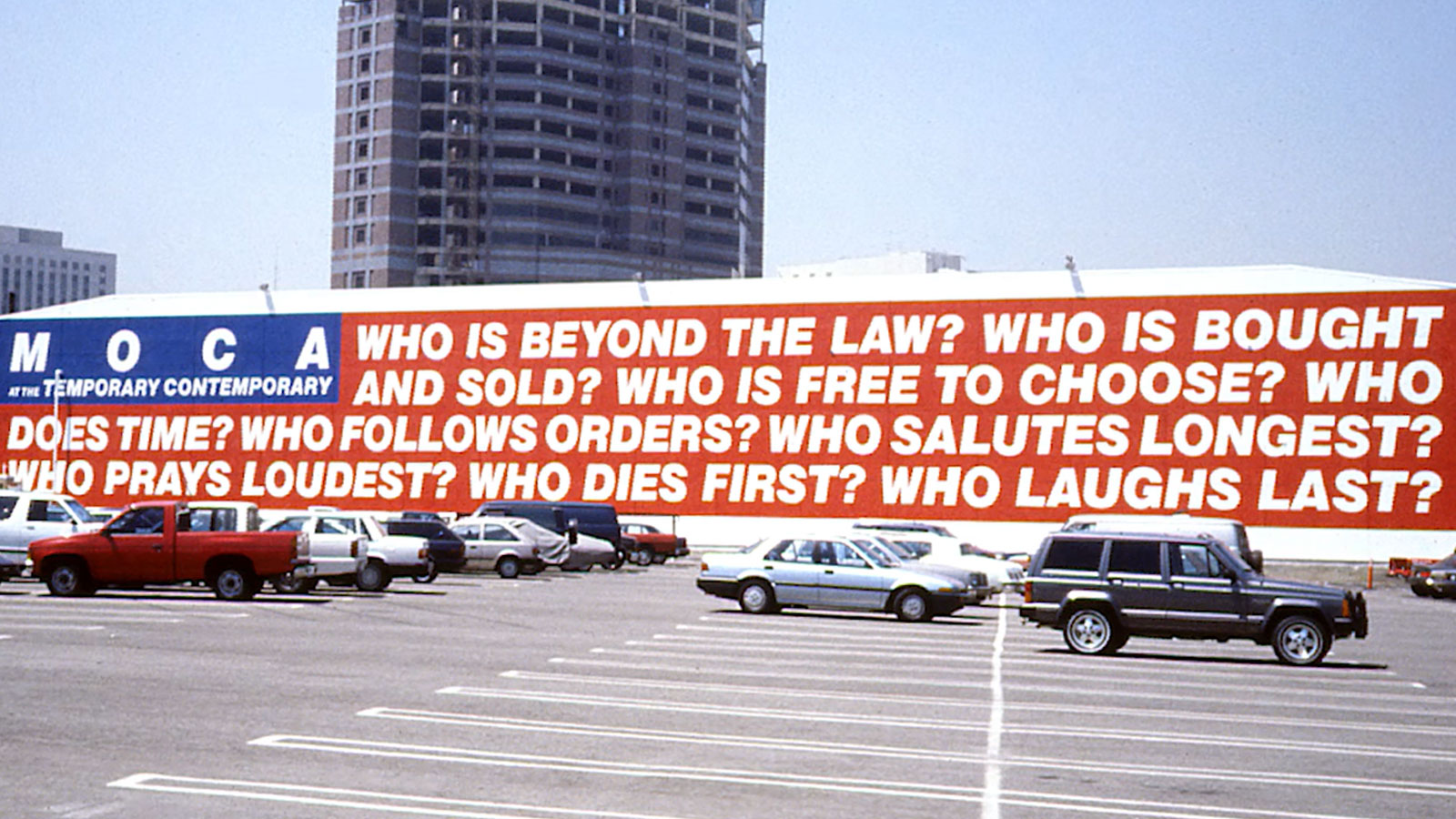

A track record like Scocca’s should have everyone in media clamoring to hire him. Why does that not happen? Even as the literal Nazis and assorted crackpots are raking it in with their pyrotechnically awful newsletters on Substack? What is the context in which these things are taking place? Who is allowed to have an opinion??

Full disclosure, the publication you’re reading is referenced in Scocca’s essay; he was Popula’s editor-in-chief for four months, a gamble I was thrilled to take when we were able to raise some grant money in 2022. Popula runs on a shoestring; it’s an experimental publication, ad-free and reliant on grants and donations to keep afloat. My failure (as Popula’s publisher) to raise enough to keep Scocca at the helm was especially devastating because we were just beginning to get somewhere; Tom had scored a big hit with his incisive critique of the Times’s coverage of trans issues. I’m very proud to have helped publish that.

Popula, and our new cooperative expansion, Flaming Hydra, were founded to help protect press freedom. I hope you’ll join us if, like me, you want to continue to read speech that is free of corporate control, and writing that is deeply and unapologetically opinionated.